Introduction

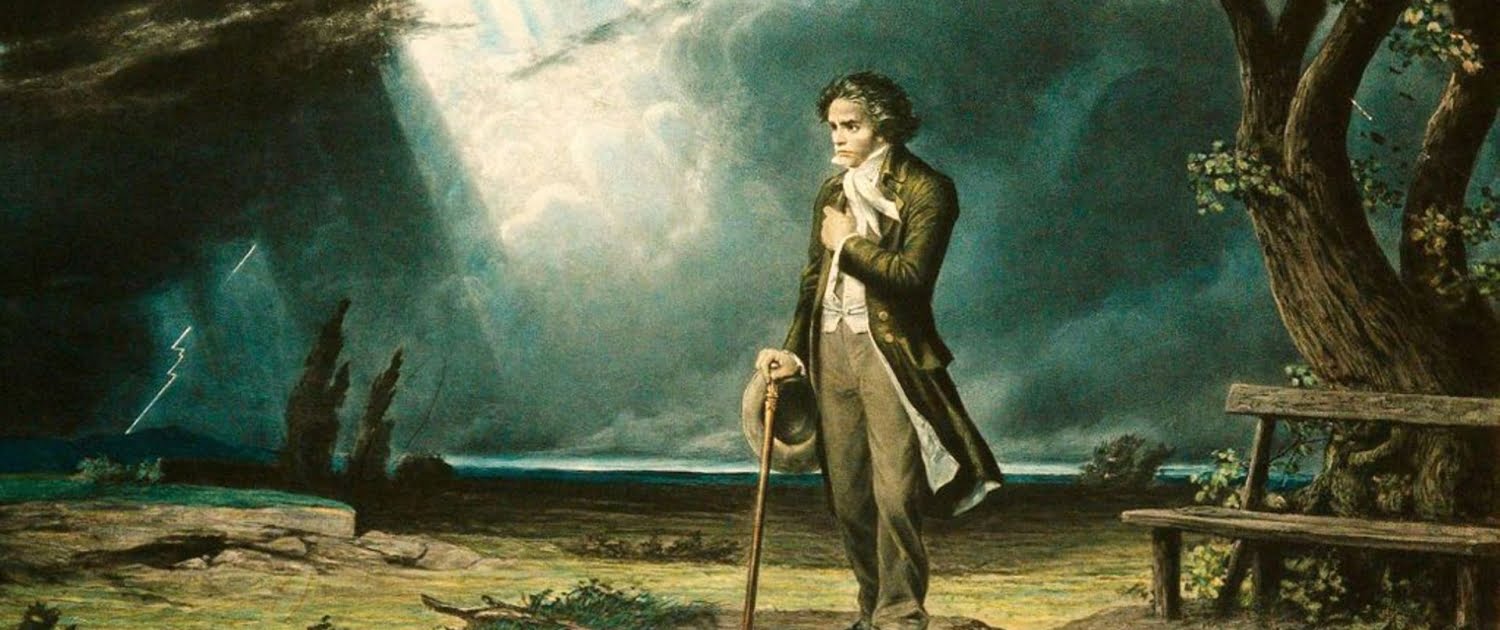

Scholarship on Ludwig van Beethoven has long addressed the composer’s affiliations with Freemasonry and other secret societies in an attempt to shed new light on his biography and works. Though Beethoven’s official membership remains unconfirmed, an examination of current scholarship and primary sources indicates a more ubiquitous Masonic presence in the composer’s life than is usually acknowledged. Whereas Mozart’s and Haydn’s Masonic status is well-known, Beethoven came of age at the historical moment when such secret societies began to be suppressed by the Habsburgs, and his Masonic associations are therefore much less transparent. Nevertheless, these connections surface through evidence such as letters, marginal notes, his Tagebuch, conversation books, books discovered in his personal library, and personal accounts from various acquaintances.

This element in Beethoven’s life comes into greater relief when considered in its historical context. The “new path” in his art, as Beethoven himself called it, was bound up not only with his crisis over his incurable deafness, but with a dramatic shift in the development of social attitudes toward art and the artist. Such portentous social changes cannot be accounted for through the force of Beethoven’s personality, or the changing role of the Viennese nobility. Many social forces were at work in the late Enlightenment period, but within this context Freemasonry assumed special importance for Beethoven.

It was not Beethoven alone who revolutionized the general perception of music, moving from a craft designed to “please the ears” or “public”, to an art whose purpose was less clear and less superficial—an art that would certainly transcend at least this mundane view of music, extending well into metaphysical and spiritual realms. While composers such as the ones above wrote with a great deal of concern for public and aristocratic taste, they nevertheless anticipated the direction in which Beethoven was to take the art. Mozart, for instance, made an attempt to support himself in the free market as a composer, though with much difficulty. Both Mozart and Haydn were also among those composers integrating themselves in an organization which was to formally resurrect to its members many of the ancient lofty and metaphysical views of music as a part of a general plan to alter, perhaps even radically, social thought: Freemasonry. Lest it be doubted that Beethoven ascribed a higher spiritual goal to his art, consider the inscription from the Temple of Isis in ancient Egypt that Kant described as perhaps the most sublime of thoughts, and that Beethoven adopted from Friedrich Schiller’s essay, Die Sendung Moses, and kept under glass at his desk during most of the last decade of his life:

I am everything, what is, what was, and what will be.

No mortal human being has lifted my veil.

The origin of Schiller’s essay, in turn, was a publication by Carl Leonhard Reinhold that was written for the Freemasons at Vienna in the 1780s.8 Schiller, like Beethoven, was closely associated with Freemasons, even if it has never been proven that he himself was a member. While the most famous composers of the world into which Beethoven entered were for the most part hanging on to the old patronage system, their involvement in Freemasonry and its ideals pointed the way for a new view of music. The impact of such a trend cannot be underestimated. In the history of music, it is one of the most direct and significant catalysts in many aspects of the following era, the Romantic Movement. Indeed, the context in which this phenomenon of deepening and spiritualizing the art of music for its own sake can be more usefully viewed within the larger context of the modernization of the Western world.

The Masonic Factor

Freemasonry is a fraternal organization at least in part dedicated to mutual aid of a restricted membership, positive social impact, and general philanthropy.37 It is also probably the most famous example of a secret society. Though its presence is obviously not at all secret, its origin, rituals, aspects of its overall purpose, moral teachings, and community involvement are all ambiguous and sources of curiosity and speculation for the general public. While there is strong evidence and documentation to provide us with answers to some common questions, it appears that much about this group remains officially unconfirmed or unknown, either to the public or perhaps even to the Masonic leadership itself. It is central to the essence of Freemasonry that its teachings and symbols work through the lens of an architectural and building perspective. For instance, Freemasonry utilizes the image of the draftsman’s right-angle square at least in part to symbolize a striving for moral straightness through the discipline of the Masonic society.38 We do know that the group can trace its origins to prototype assemblies at least as far back as the early seventeenth century. It is at this point that we have the earliest concrete documentation of a specifically Masonic source, 39 though the group likely existed in earlier forms during the Middle Ages. Literature on this topic, much of it of Masonic origin, ascribes mythical beginnings ranging as far back as the College of Roman Architects, Hiram Abiff and his work on the Hebrew Temple of Jerusalem with King Solomon,40 or even ancient Egypt.41 Through the Middle Ages up until the early eighteenth century, the group developed an educational and spiritual self-sufficiency. This was a necessity resulting from the traveling that was imperative for their work: whenever one project was completed, they needed to travel to their next project. The best builders could be expected to be summoned across large distances in Europe.

The professional nature of this group was in some ways peculiar in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Relatively frequent traveling kept them from forming community roots wherever they stationed themselves. This stands in stark contrast to most Europeans who remained bound to one place for generations as a result of widespread feudalism. It also would likely encumber facility in communication with surrounding people and authorities, as the language and dialect, as well as the culture would usually not be one’s own. The work was also intense, so outside socializing would not necessarily occur frequently. The business aspect of dealing with the Catholic Church also likely had a de-mystifying effect that would not likely be shared or understood by the majority of Christians of the time. Such insularity and feeling of social difference would most likely have been reciprocated and intensified by the surrounding community.

Yet, these traveling builders required great knowledge, skill, and social discipline to support their activities. The solution that appears to have arisen was to educate themselves. While today, this may seem unremarkable, it becomes significant that these builders developed their skill, science and social organization largely apart from the dominant ecclesiastical forces that shaped the rest of society around them. Some pagan traditions were retained, and some ancient educational tactics were developed and employed, such as dividing knowledge into the seven liberal arts.42 The lifestyle of these groups had set them apart from the rest of Europe, and the isolation grew into a culture within a culture, with its own insights and perspectives as well as those of its surrounding world.

Because of its characteristic secrecy, it cannot be stated with authoritative certainty what was taught in these guilds or in the modern lodges of Freemasonry. Nor is it clear what the exact scope of Masonic study included at any given historical point. Through its existence, nevertheless, information about the organization has emerged from various venues, such as membership lists, publications of essays initially intended for Masonic audiences, or minutes of meetings that somehow ended up in public libraries or private collections. In any case, at least part of the curricula that could be studied in the lodges has therefore become known. While the subjects were wide-ranging, for the purposes of this study, I will list a limited and relevant selection.

In any given Masonic literature, a strong element of Judeo-Christian esoterica prevails. This appears to be the most fundamental element of the group’s spiritual system, with a heavy emphasis on the Hebrew lore of the Old Testament. In particular, the passages dealing with the Temple of Solomon in the book of Kings and Chronicles hold central meaning and symbolism for the group. Studies of Greek thought are prevalent as well throughout Masonic sources, especially Pythagoreanism. The Greek myths are also frequently referenced. Egyptian, Babylonian, and other Middle Eastern belief systems and lore are present as well, as are resulting syntheses such as Hermetism and Neo-Platonism. The Freemasonry from Beethoven’s time also includes a heavy element of ancient Egyptian influence:43 “Egyptomania gripped the educated classes.”44 Hinduism certainly captured the Masonic imagination as can be gathered from contemporary writings, but it likely became an integral part of the Masonic system at least as early as the late eighteenth century when men such as Hammer-Purgstall, William Jones, and Herder, himself a Mason, were writing about it in lofty tones.

It seems that no spiritual system appeared uninteresting to Masonic thinkers; reading Masonic discourse reveals a striving for this kind of awareness. It must also be noted that this erudite literacy extended well into the mathematical and astronomical aspect of each culture studied. Whether or not these subjects were all present in the early centuries of Freemasonry is difficult to ascertain, but the inclination to scrutinize these venues must have been very present from early in its history.

To summarize: in its general philosophy, Freemasonry also assimilates thought from, but not limited to, the following: paganism, the Kabbala, Hermetism, ancient Egyptian thought, Rosicrucianism, Alchemy, Theurgy, Platonism, Neo-Platonism, various mystery schools, the Knights Templar, various philosophical and scientific studies, Islam, Christianity, and Hinduism. In the early to mid-seventeenth century, English Masonic lodges began to admit nonstoneworkers, accepting dedicated and distinguished men for their ranks. This expanded the membership from professional Masons, who practiced operative Masonry, to those who acquainted themselves purely with the non-physical dimension of Freemasonry, which was rooted in metaphor and symbolism. It is this latter form with which it is now most associated. This theoretical and philosophical study of the Craft (Freemasonry) became known as speculative Freemasonry in distinction to operative Freemasonry, which dealt with the physical practice of construction. Whether this was a result of pressure from curious scholars and nobles, or a persuasive stratagem of the Masons to procure positions of large-scale social influence, desire to spread philosophical thought, or any other specific reason is unclear. Whatever the case, the Masonic community since then has become primarily an organization consisting of men of extremely varied backgrounds, fulfilling a spiritual/moral/intellectual purpose for its members rather than merely a practical architectural, engineering, or brick-laying one as had likely been a primary dimension of the group its earliest times.

Freemasonry, developing into its speculative state as we know it today, began its ascent to international influence in 1717, when Masonic lodges in London bound themselves into an organization with centralized authority. After this point, Masonic influence quickly spread to mainland Europe via France, and within several short decades, throughout the German-speaking lands.45

The admittance of non-stone workers into Freemasonry was a major social occurrence that moved in tandem with the blossoming of the Enlightenment. While many fine points of Freemasonry remain even now disputed or misunderstood, it is evident that the group has been driven toward social reform at least in a broad sense.46 As it became fashionable and advantageous for monarchs to become or appear benevolent and/or enlightened despots, Freemasonry provided a venue in which they might develop themselves in various ways without publicly losing face or threatening their power. It was also prestigious to be initiated into a society that was shortly before a restricted one, reputed to hold esoteric secrets. Conversely, the growing influence of egalitarian ideals as exemplified by the Freemasons, ever growing in stature and power at that time, applied pressure on all European monarchies to concur with these trends. The struggle between the ideals of Freemasonry and the preservation of aristocratic systems developed into a waxing and waning battle. When the teenaged Beethoven was old enough to begin partaking in Freemasonry, which given his professional and personal background, would have been a logical step, Imperial favor again fell with concrete consequences for these groups. Several repeals of the freedom of Freemasons to assemble occurred at this time. In Bavaria in 1784, its Elector banned secret societies. Later, on March 2, 1785, a further prohibition was issued banishing the Illuminati founder, Adam Weisshaupt.47 The son of a Freemason, Emperor Joseph II was on some level appreciative of the Masonic social contribution48 which largely coincided with his own social agenda. He was nevertheless wary of the group’s secrecy, and consequently imposed the Freimaurerpatent, a prohibition of secret assembly on December 11, 1785.49

Shortly after Masonic lodges opened their doors to aristocrats and men of distinguished learning for speculative membership, men of distinction from various fields were both attracted to and recruited by the group. The abstract, metaphorical outlook and philosophies proved fascinating and/or inspiring to many of Europe’s leading intellects of the day. By Beethoven’s time, aristocrats were joined by doctors, artists, lawyers, military men, and many other significant figures in seeking admittance into the ranks of the Masons.

Prominent Masons/Illuminati in Beethoven’s World

Footnotes

8 A recent and detailed study of this and two other ancient Egyptian inscriptions embraced by Beethoven is Beethovens Glaubensbekenntnis: Drei Denksprϋche aus Friedrich Schillers Aufsatz Die Sendung Moses, edited with a commentary by Friederike Grigat (Bonn: Beethoven‐Haus, 2008).

37 The outside opinion of the purpose of Freemasonry varies a great deal, but these descriptions seem to reflect the self‐image of Freemasonry. This impression is encapsulated in the writings of Albert Pike, a prominent American Masonic leader of the nineteenth century. See his Meaning of Masonry.

38 Mackey, Albert G., The Lexicon of Freemasonry, pp. 450‐451.

39 McIntosh, Christopher, Rose Cross, p. 39. McIntosh cites Elias Ashmole’s initiation into a Masonic Lodge in 1646.

40 Ibid., chap. 24 and 43.

41 Howard, p. 5.

42 Although some authors imply this to be a Masonic development, this division seems to have been borrowed from the standard curricula of Gothic universities, founded in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. Older roots of division of knowledge still can be seen in works such as Aristotle’s Metaphysics. See also footnote 51.

43 For instance, Peter Branscombe cites Ignaz von Born’s essay, Über die Mysterien der Aegyptier, as an influential work within the Masonic community in Die Zauberflöte, p. 20.

44 Solomon, Late Beethoven, p. 147

45 McIntosh in Rose Cross states the date of the first recorded German Masonic lodge as 1737, p. 42.

46 While this view of Freemasonry can be sensed in most of its literature, one may consult Albert Pike’s The Meaning of Masonry as an authoritative statement of the group’s self‐image. Though this address was likely written at least 25 years after Beethoven’s death, its principles seem consistent with those reflected in various sources from Beethoven’s life.

47 Nettl, Mozart and Freemasonry, p. 9.

48 Einstein, Alfred. Mozart, p.82. More details appear at: http://www.mastermason.com/wilmettepark/mozart.html This source cites: “An e‐Zine of Masonic Re‐Prints and Extracts from various sources. Compiled by Hugh Young linshaw@cadvision.com”. It credits specifically: “BROTHER MOZART AND “THE MAGIC FLUTE” by Newcomb Condee 33 deg”. Here, in the Masonic viewpoint, is described an official statement from Joseph II of 1785 on the Freemasons that limits the group’s membership, but acknowledges its social advantages.

49 Nettl, Mozart and Freemasonry, p. 12.

50 McIntosh, Rose Cross, p. 35.

51 Nettl, Mozart and Freemasonry, pp. 9‐10.

52 Einstien, Mozart, p. 83. Einstein states that this excerpt was taken from Weisshaupt’s “sketches of the statutes of the order.”