Introduction

The Great Pyramid of Giza, an enduring symbol of ancient Egyptian ingenuity, has long been attributed to Pharaoh Khufu’s reign, traditionally dated to 2589–2566 BC. However, establishing its precise construction date has proven challenging due to inconsistencies in radiocarbon data and reliance on textual evidence like the Wadi el-Jarf Papyri. Discovered in 2011 at a 4th Dynasty harbour site on Egypt’s Red Sea coast, the papyri, particularly the Diary of Merer which provides the only direct documentary evidence linking the pyramid’s construction to Khufu’s 26th–27th year (c. 2566 BC)[1]. Yet, their authenticity is here brought under scrutiny due to the absence of dust on the in-situ fragments, despite a supposed 4,500-year burial. New insights from the Wadi el-Jarf site, radiocarbon dating of the Great Pyramid’s mortar, and regional chronologies from the Early Bronze (EB) I-II period in the southern Levant further complicate the timeline, raising questions about the papyri’s legitimacy. This article explores these challenges, the archaeological context of Wadi el-Jarf, and the urgent need for scientific verification to resolve questions of authenticity.

Challenges in Dating the Great Pyramid

A fragment of the Wadi el-Jarf Papyri, showing the hieratic script detailing logistical operations.

Historical records, such as king lists and the Wadi el-Jarf Papyri, place the Great Pyramid’s construction during Khufu’s reign, around 2560 BC. However, these records lack astronomical anchors like Sirius risings, which fix later Egyptian chronologies (e.g., Middle Kingdom, 2040–1782 BC)[2]. The First Intermediate Period (2181–2040 BC), a time of political fragmentation, creates a chronological gap with uncertain duration estimates ranging from less than a century to over 150 years[2]. Radiocarbon dating of organic materials in the pyramid’s mortar offers a potential scientific solution, but inconsistencies in the results, combined with regional dating challenges, have complicated efforts to confirm the historical timeline.

Radiocarbon Dating of the Great Pyramid Mortar

Two major radiocarbon studies, conducted in 1984 and 1995, analyzed organic inclusions in the Great Pyramid’s gypsum mortar, primarily charcoal fragments (1–2 mm) from fires used to heat gypsum during construction[3][2]. Samples were taken from the outer casing, core, and likely the relieving chambers above the King’s Chamber, areas less prone to contamination[3].

A total of 42 samples were dated from the Great Pyramid. 20 in 1984 and 18 (plus 4 additional) in 1995[2]. Across both studies, 235 samples were dated from Old and Middle Kingdom monuments, with the Great Pyramid as a primary focus[3]. The study yielded an average calibrated age of 2917 BC (range: 2853–3809 BC), 351 years older than Khufu’s historical dates (2589–2566 BC). The 1995 study averaged 2694 BC (range: 2977–3740 BC), 128 years older, with a 400-year spread, indicating significant inconsistency[2]. Statistical analysis (chi-square tests) showed low consistency, with dates not aligning as a single construction event[3].

The old wood effect is a major contributor. Acacia, a common fuel, may have been centuries old when used, skewing dates earlier[2]. Ancient practices of using dead wood or reused charcoal (stored for long periods) further complicate results[2]. Contamination from later repairs and calibration plateaus also widen the date ranges[3].

The 400-year spread and older-than-expected means (300–500 years off historical dates) make the mortar dates unreliable for precise dating. However, the 1995 mean (2694 BC) is closer to 2566 BC, offering tentative support for the traditional timeline, if corroborated by other evidence like the Wadi el-Jarf Papyri.

But that’s not the end of it. From The Ethical Skeptic:

…various carbon-14 dating efforts were conducted in 1984 and 1995 on samples of kiln-fired mortar (bound charcoal and charcoal VOCs) taken from service bakeries and structures nearby the Khufu pyramid. As a group, these were dated to 1480 years older than the Fourth Dynasty legendary dates of construction.4 Much of the mortar was contemporary with the Dixon Relic cedar-like plank carbon-14 dating and presented a significant problem for the Fourth Dynasty Narrative. These Egyptians were not using 15 to 1500 year old wood to fire their kilns—this is guaranteed. To date, there has not been a single published carbon-14 dating of mortar from inside the Khufu pyramid, much less from inaccessible areas. What little study has been completed, outlined below, was forced by alternative researchers and would never have been undertaken by academic archaeology.

But this does not stop dishonest Narrative apologists from using hocus-pocus adjustments to recalibrate the carbon-14 results for only the 46 Fourth Dynasty samples7 along with semantic sleight-of-hand to imply that kiln-fired mortar charcoal samples were extracted from the Great Pyramid itself—when none were actually taken from it at all.8 Even if samples had been taken from Khufu, the Narrative remains falsified, while alternative evidence remains not only plausible, but probable. – Hidden in Plain Sight

Early Bronze I-II Chronology in the Southern Levant

The EB I-II (Early Bronze) period in the southern Levant provides a regional context for the Great Pyramid’s timeline (Dynasty 4, c. 2560 BC), overlapping with the EB I-II transition (c. 3100–2900 BC). Radiocarbon dates from EB I-II sites show similar inconsistencies to the Great Pyramid mortar, reflecting systemic dating challenges in the region[4].

- EB I Onset: Traditionally dated to c. 3500 BC, new dates from Afridar (Areas E and G) suggest 3956–3378 BC[4]. Excavators argue these are residual from Chalcolithic contexts, favoring a mid-4th millennium date (c. 3500–3400 BC) based on sites like Kabri and Taur Ikhbeineh[4].

- EB I-II Transition: Correlates with Egypt’s Dynasty 1 (c. 3150–2950 BC). Abydos dates (Tomb U-j, Scorpion I) range from 3376–3223 BC, aligning with a high chronology (c. 3100 BC)[4]. Late EB I sites (HIT, Palmahim Quarry) yield 3334–2910 BC, but old wood effects skew results, suggesting 3100–2900 BC[4].

- Consistency: EB I-II dates are inconsistent, with spreads up to 400 years, mirroring the Great Pyramid mortar issues[4].

The EB I-II transition (3100–2900 BC) precedes Khufu’s reign, placing 2566 BC in EB II. This regional alignment supports the papyri’s timeline, but the dating inconsistencies highlight broader chronological challenges.

The Wadi el-Jarf Papyri and Their Archaeological Context

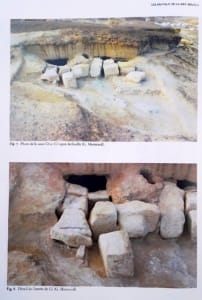

Photographs of the Wadi el-Jarf site, including the sealed storage galleries (G1 and G2)

The Wadi el-Jarf Papyri were discovered at a 4th Dynasty harbor site, 24 km south of Zafarana on the Red Sea coast, at the foot of Mount Galâlâ near Wadi Deir[1]. The site, first noted in the 19th century by J.G. Wilkinson and rediscovered in the 1950s by French pilots, spans a 5 km area from the desert hills to the coast[1]. Excavations began in 2011, led by Pierre Tallet and El Sayed Mahfouz, revealing a complex of 25–30 rock-cut galleries, a large dry stone building (60 x 30 m), a wharf, and evidence of pottery production[1]. Pottery and structural evidence date the site to early Dynasty 4 (c. 2600 BC), making it the oldest known harbor in the world[1].

The galleries, used for storage, contained boat parts (e.g., a 2.75 m floor frame, oars, ropes), large storage jars with red hieroglyphic inscriptions, and a papyrus fragment with unreadable hieratic text[1]. The wharf, an L-shaped structure partly underwater, sheltered 21 stone anchors, confirming seafaring activities to South Sinai (e.g., El-Markha/Tell Ras Budran) and possibly to Punt in the southern Red Sea[1]. An inscription in gallery G3 names the scribe Idu from the Fayum, suggesting expedition routes via the Wadi Araba[1].

The papyri, found in galleries G1 and G2 detail the transport of limestone to Giza for the Great Pyramid, aligning with Khufu’s reign. However, in-situ photographs of the papyri fragments from Tallet’s Les papyrus de la mer Rouge I raise some interesting questions with regard to the apparent the lack of dust on the papyri, despite 4,500 years in a sealed gallery. Stone fragments on the papyri indicate minimal cleaning, yet no sediment is present, even though the gallery’s sandstone ceiling should have produced dust through internal erosion (0.1–0.5 mm per century, equating to 4.5–22.5 mm over 4,500 years)[5].

Original Caption (emphasis added): “Accounts papyri from Wadi el-Jarf at the time of the discovery, before conservation. The major surviving papyri record the activities of an official called Inspector Merer, in charge of a work-gang whose activities included delivering stone down the Nile to the Great Pyramid construction site at Giza.

Seismic Activity and Environmental Conditions

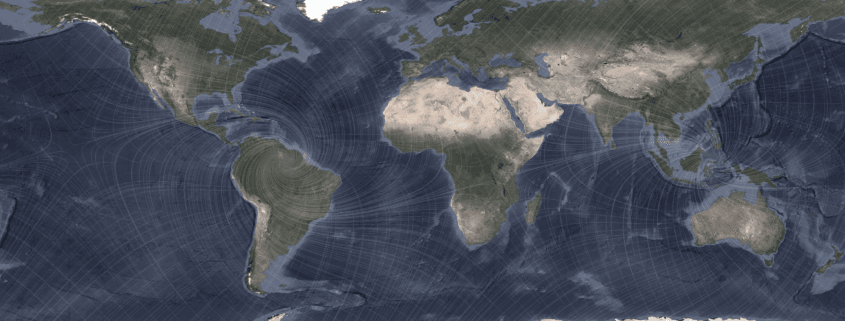

Wadi el-Jarf lies in the Gulf of Suez, a seismically active region near the Red Sea Rift, where the African and Arabian plates diverge at a triple junction with the Sinai microplate. Historical data includes the 1969 Shedwan Island earthquake (magnitude 6.6), and recent events like the 16 June 2020 quake (magnitude 5.4) highlight ongoing activity. The Egyptian National Seismic Network records hundreds of microearthquakes (magnitude < 3) annually, with magnitudes up to 5.5 every few decades. Over 4,500 years, thousands of tremors would have dislodged dust from the gallery ceiling, accelerating sediment accumulation. The papyri’s clean state, despite this seismicity, suggests they were not exposed to these conditions for the full duration, reinforcing the forgery hypothesis.

A map illustrating Wadi el-Jarf’s location on the Red Sea coast, relative to the Red Sea Rift and Gulf of Suez, highlighting the seismic context.

Other Artifacts and Comparative Analysis

The Wadi el-Jarf site yielded additional finds: ceramic jars, boat fragments, ropes, and stone anchors, dated to early Dynasty 4 via pottery evidence[1]. The site’s scale and features (e.g., the wharf, storage galleries) mirror other Red Sea harbors like Ayn Sukhna, where similar galleries, boat remains, and inscriptions from Dynasty 5 (e.g., Djedkare-Isesi, c. 2400 BC) confirm seafaring to Sinai[1]. While the dating of these artifacts isn’t directly relevant to the papyri’s authenticity, their condition could provide a baseline. If they show dust accumulation consistent with 4,500 years, it would highlight the papyri’s anomaly. Reports on their condition are unavailable, but the expectation of dust on all items underscores the papyri’s unusual state.

Forgery Hypothesis and Archaeological Fraud

The papyri’s singular importance heightens the motive for forgery. A forger could have planted them in a 4th Dynasty site, crafting content to match the expected 2560 BC timeline, unaware that mortar dates suggest an older pyramid (e.g., 2917 BC). The lack of dust aligns with recent placement, and archaeology’s history of fraud (e.g., Piltdown Man, Shinichi Fujimura) shows high-stakes finds are targets. The project’s funding by the Honor Frost Foundation suggests oversight, but fraud remains possible given the academic stakes.

The Need for Scientific Verification

To resolve the authenticity debate, scientific tests are essential:

- Carbon Dating: Would confirm the papyri’s age (c. 2600 BC vs. modern). A recent date would explain the lack of dust, confirming forgery.

- Sediment Analysis: Checking for ceiling sediment would verify long-term burial, addressing the dust anomaly.

No such tests are documented, leaving a critical gap. The dust anomaly, seismic context, mortar dating inconsistencies, and regional chronological challenges necessitate verification to ensure this pivotal evidence isn’t a modern fabrication.

Conclusion

Dating the Great Pyramid remains a complex challenge, with radiocarbon dates of its mortar showing a 400-year spread (2917 BC in 1984, 2694 BC in 1995) due to old wood effects, and EB I-II dates in the southern Levant (3100–2900 BC transition) exhibiting similar inconsistencies. The Wadi el-Jarf Papyri, discovered at the world’s oldest harbor dated to Dynasty 4, offer a precise timeline (2566 BC), but their authenticity is uncertain. The lack of dust, despite 4,500 years in a seismically active region, suggests recent placement. Carbon dating and sediment analysis of the papyri are essential to confirm their place in history, ensuring the Great Pyramid’s construction timeline is accurately understood.

References

References

- Tallet, P. 2012. Ayn Sukhna and Wadi el-Jarf: Two newly discovered pharaonic harbours on the Suez Gulf. British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18: 147–68. https://www.britishmuseum.org/PDF/Tallet.pdf

- Koch, D.H. Pyramids Radiocarbon Project. 1999. Dating the Pyramids. Archaeology 52(5): 26–33. https://www.academia.edu/36645783/Dating_the_Pyramids

- Bonani, G., et al. 2001. Radiocarbon Dates of Old and Middle Kingdom Monuments in Egypt. Radiocarbon 43(3): 1297–1320. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/655378

- Braun, E. 2001. Proto, Early Dynastic Egypt, and Early Bronze I-II of the Southern Levant: Some Uneasy 14C Correlations. Radiocarbon 43(3): 1279–1295. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/655378

- Journal of Cave and Karst Studies. 2019. Dust accumulation rates in sealed karst caves: Implications for archaeological preservation. 81(2): 92–104. https://legacy.caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/v81/81_2_Full-online.pdf