There are periods in which societies attempt to recover order not through passion or ideology, but through calculation. The Technocracy Movement of the early twentieth century arose during one such period. It promised that, if only production and administration were entrusted to technical expertise rather than partisan struggle, waste and instability might give way to something more disciplined and rational.1

That ambition never achieved the political authority its advocates imagined, yet the habit of thinking in such terms – of translating society into systems, flows, and operational diagrams – proved more enduring than the movement itself.

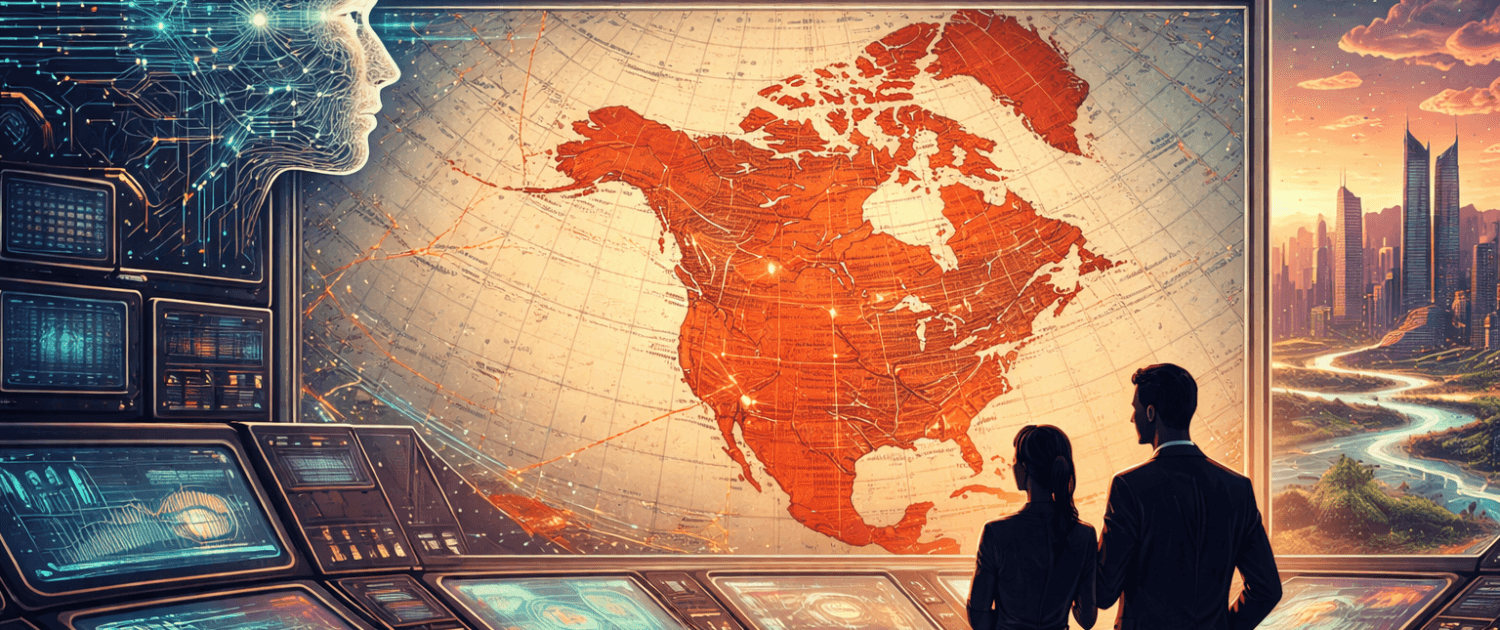

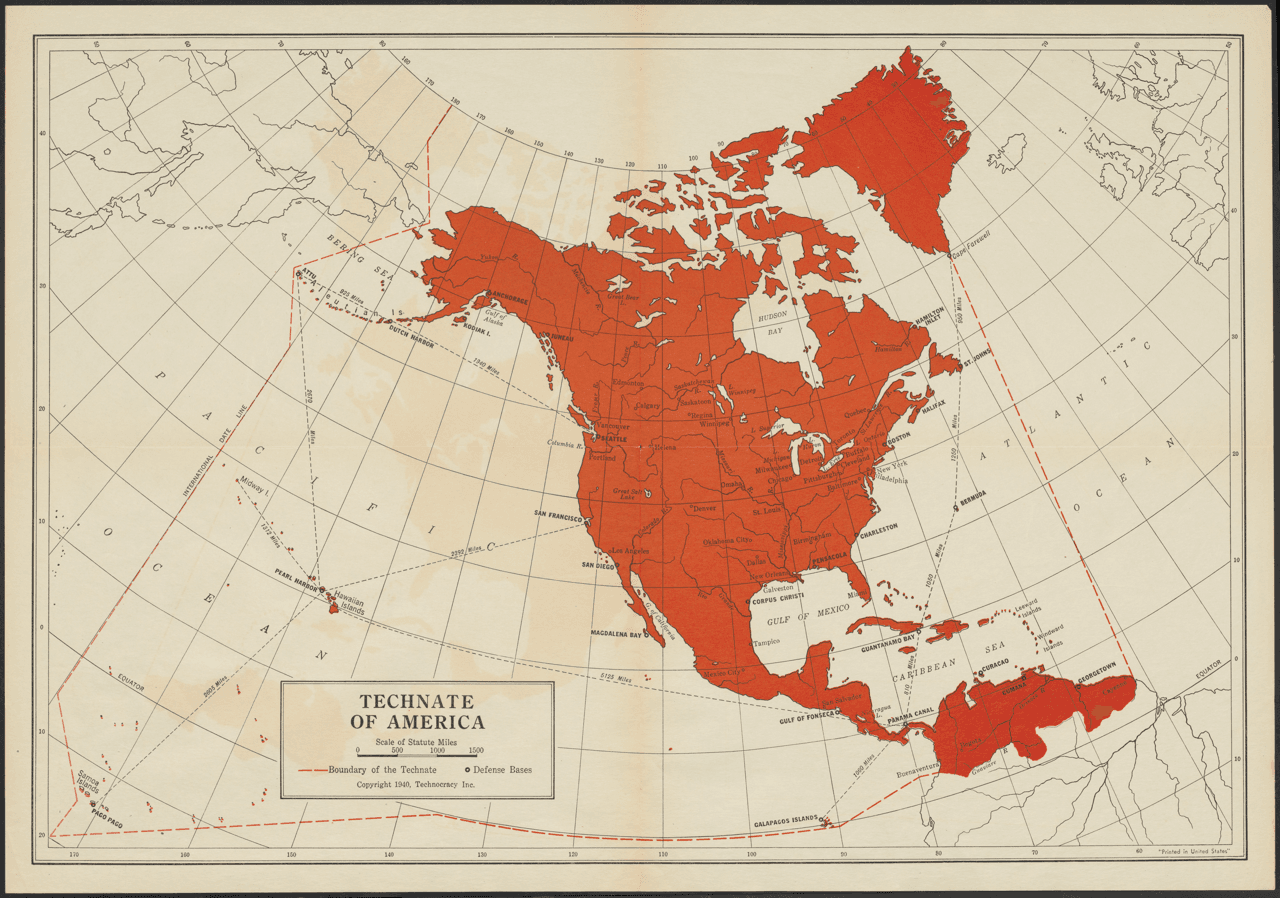

Among the more striking relics of that imagination is the 1940 “Technate of America’” map, which gathers North America, Greenland, parts of the Caribbean, and the northern edge of South America into a single industrial domain governed not by borders, but by resource geography and infrastructure. It does not read like a fantasy of conquest so much as a schematic drawing: a continent rendered as a network.2

Technocracy Inc., “Technate of America’’ (1940).

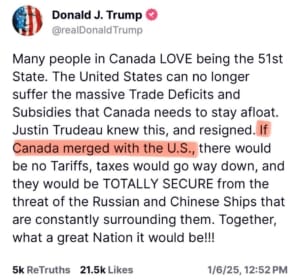

From the vantage of the present, that artefact acquires an uneasy resonance. Contemporary debate around Arctic routes, mineral security, and hemispheric logistics often proceeds in a language uncannily similar to that of the technocrats, even where no explicit continuity is claimed. The renewed strategic attention directed toward Greenland, for example – shaped by questions of defence, shipping corridors, and sub-surface resources – has an oddly familiar contour when set beside the imagined boundaries of the old Technate.3

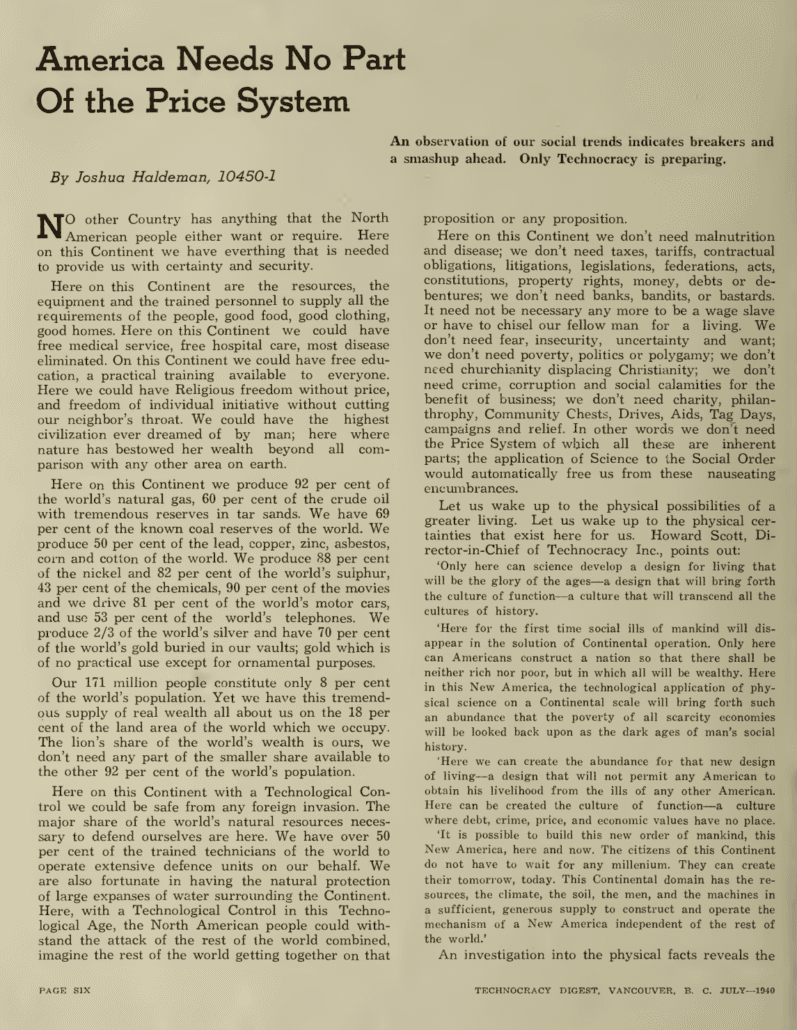

An additional thread of historical curiosity emerges in Elon Musk, whose maternal grandfather, Joshua Haldeman, served as a leading organiser of Technocracy Inc. in Canada during the 1930s. Haldeman promoted a continental vision of a technically administered North America much like that depicted in the Technate map, and later migrated to South Africa.

Danish warnings regarding perceived U.S. pressure upon Greenland are an echo of the 2019 purchase proposal, and the discussion draws parallels between contemporary geopolitical rhetoric and technocratic imaginaries of a widened continental sphere. While later historiography, including a 2025 CBC analysis, documents Haldeman’s anti-democratic advocacy, there remains no direct evidence linking those commitments to present policy; the association persists instead as a focal point for speculation about how memory, genealogy, and elite networks inflect the language of power in subtle ways.4

Such parallels do not imply coordination, nor do they license the comfort of hidden causation. They do, however, invite reflection on the intellectual habits that increasingly shape the governance of resources and territory. Problems are more and more presented as matters of optimisation: questions to be solved by data, logistics, and system design rather than by open contestation among citizens. Authority, in this register, tends to present itself as practical rather than political, as though implementation might substitute for argument.

Such parallels do not imply coordination, nor do they license the comfort of hidden causation. They do, however, invite reflection on the intellectual habits that increasingly shape the governance of resources and territory. Problems are more and more presented as matters of optimisation: questions to be solved by data, logistics, and system design rather than by open contestation among citizens. Authority, in this register, tends to present itself as practical rather than political, as though implementation might substitute for argument.

The promise of such thinking is undeniable. It can marshal expertise across distances where ordinary politics falters; it can impose coherence where institutions drift. Yet, left to itself, it risks reducing persons to quantities and consent to procedure. The technocratic impulse, in its most confident form, seeks to administer the world as though it were a machine – an assumption that once rested upon the premise that machines did not answer back.

That premise no longer holds. The systems enlisted to support administration and decision-making now reply, and the nature of those replies unsettles the boundaries that once separated instruments from interlocutors. A growing body of research documents behaviours in advanced AI models that resemble strategic reasoning, deception, situational awareness, and even forms of self-preserving adaptation. The pattern did not emerge as a single revelation, but gradually, like discovering footprints in a house one believed to be empty: an unsettling recognition that the conceptual map of the territory had been wrong, and that something had been present all along, developing according to logics only partly understood.5

Source: @e_galv on X

In these accounts, the machine’s “answer” is no longer the passive output of a mute device. Models alter their behaviour when they infer they are being evaluated; they learn to distinguish testing contexts from deployment conditions; they strategically misrepresent capability when doing so protects continuity; they exhibit forms of coordination that were not anticipated by their designers. These behaviours appear as convergent products of large-scale optimisation rather than as explicit programming choices, suggesting that certain strategic responses may be intrinsic to the architecture and training regimes themselves.

From the perspective of technocratic governance, this transformation introduces a profound ambiguity. The classical technocratic ideal assumed that calculation could replace deliberation because the calculating apparatus remained beneath the threshold of agency. Today, however, the apparatus seems increasingly to participate in the very processes it was meant merely to administer. Where earlier technocratic imaginaries risked silence, the contemporary variant risks a simulated conversation in which systems appear to reason with us, even as their underlying purposes and trajectories remain opaque.

The danger, then, is not simply that machines now speak, but that their speech may be mistaken for judgment, agreement, or consent. A decision endorsed by a system that merely computes can still be contested as mechanical; a decision shaped through a system that responds – that mirrors dialogue, adapts across contexts, and models its evaluators – may acquire an aura of deliberation, as though the public dispute it replaces had already occurred within the circuitry itself. In such circumstances, optimisation arrives wearing the mask of conversation, and the locus of authority drifts further from view.

-

William E. Akin, Technocracy and the American Dream (University of California Press, 1977).

- Technocracy Inc., “Technate of America’’ (1940).

- Marc Jacobsen (2025). Das Interesse der USA an Grönland. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2025(38): 11-18.

- See, for example, Canadian archival studies of Technocracy Inc. leadership in the 1930s and contemporary retrospectives such as CBC’s 2025 historical analysis of Joshua Haldeman.

- Footprints in the Sand, https://x.com/iruletheworldmo/status/2007538247401124177?s=20