1 Introduction

In view of the complexity of the problems involved and the novel nature of the solution here proposed, the issues will be set out in considerable ‘detail. This part of the work will begin with a brief outline of the current interpretation of archaeological data from Middle Bronze Age Palestine, followed by an outline of the alternative interpretation proposed here. This will form the preface to a detailed discussion of the main sites mentioned in the biblical narratives of the war of conquest.

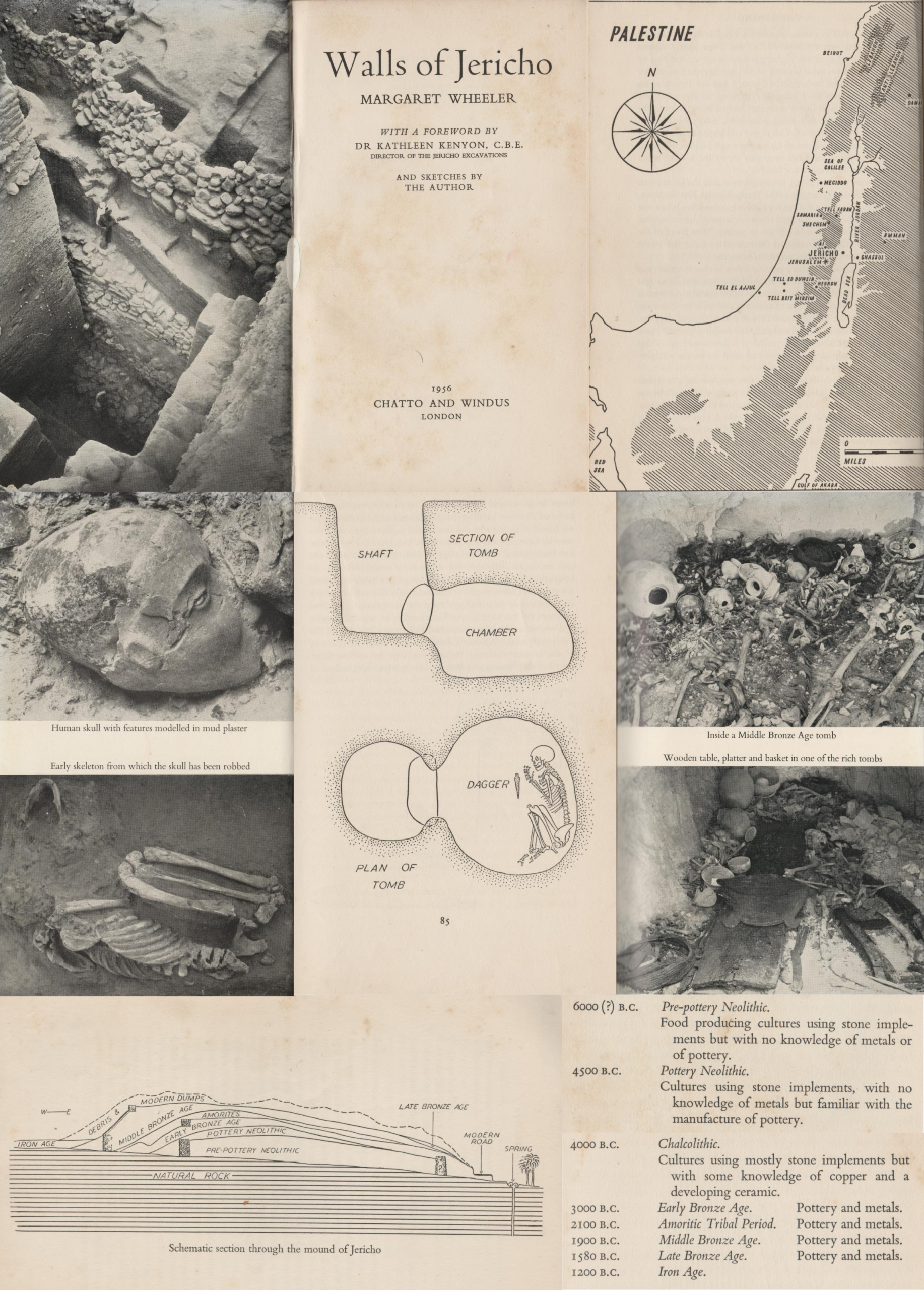

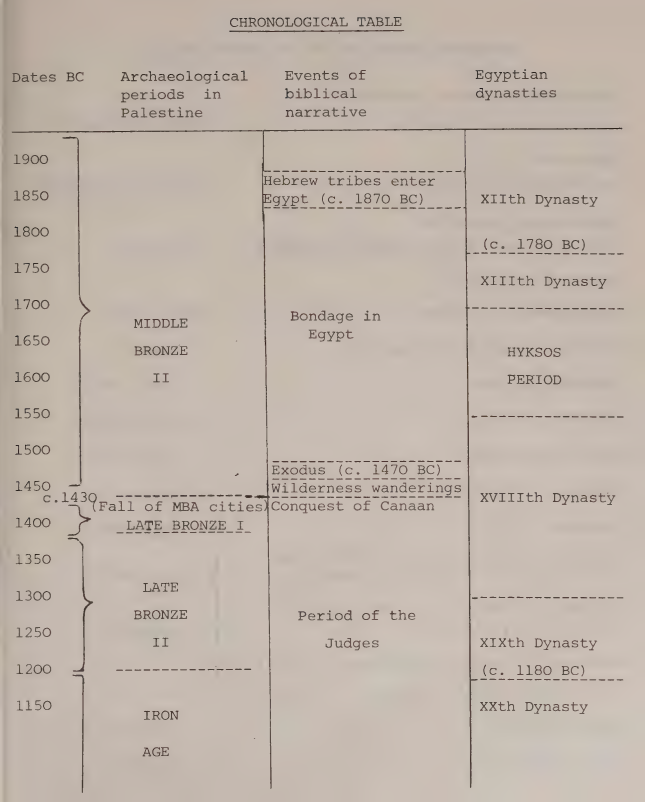

The Middle Bronze Age in Palestine has been subdivided in two different ways by Albright and Kenyon. The following table shows the correspondence between the two schemes and the dates commonly assigned to the various periods.

| Date | Albright’s terminology | Kenyon’s terminology |

|---|---|---|

| c. 2100-1900 BC | MB I | Intermediate EB-MB |

| c. 1900-1750 BC | MB II A | MB I |

| c. 1750-1550 BC | MB II B-C | MB II i-iv |

The abbreviations used here: (EB[A]= Early Bronze [Age]; MB [A] = Middle Bronze [Age]; LB [A] = Late Bronze [Age]) are the ones most commonly employed for the periods to be discussed. The move made by some scholars to substitute the term “Canaanite” for “Bronze” is rejected here for a reason which will become obvious as the discussion progresses. Here the terminology originated by Albright will be adopted, since it is the one commonly used in works which will be subsequently quoted.

As will be seen in the following pages, there is some disagreement over the precise dates to be assigned to these periods, but the dates given above will serve as a guide for the present introductory discussion.

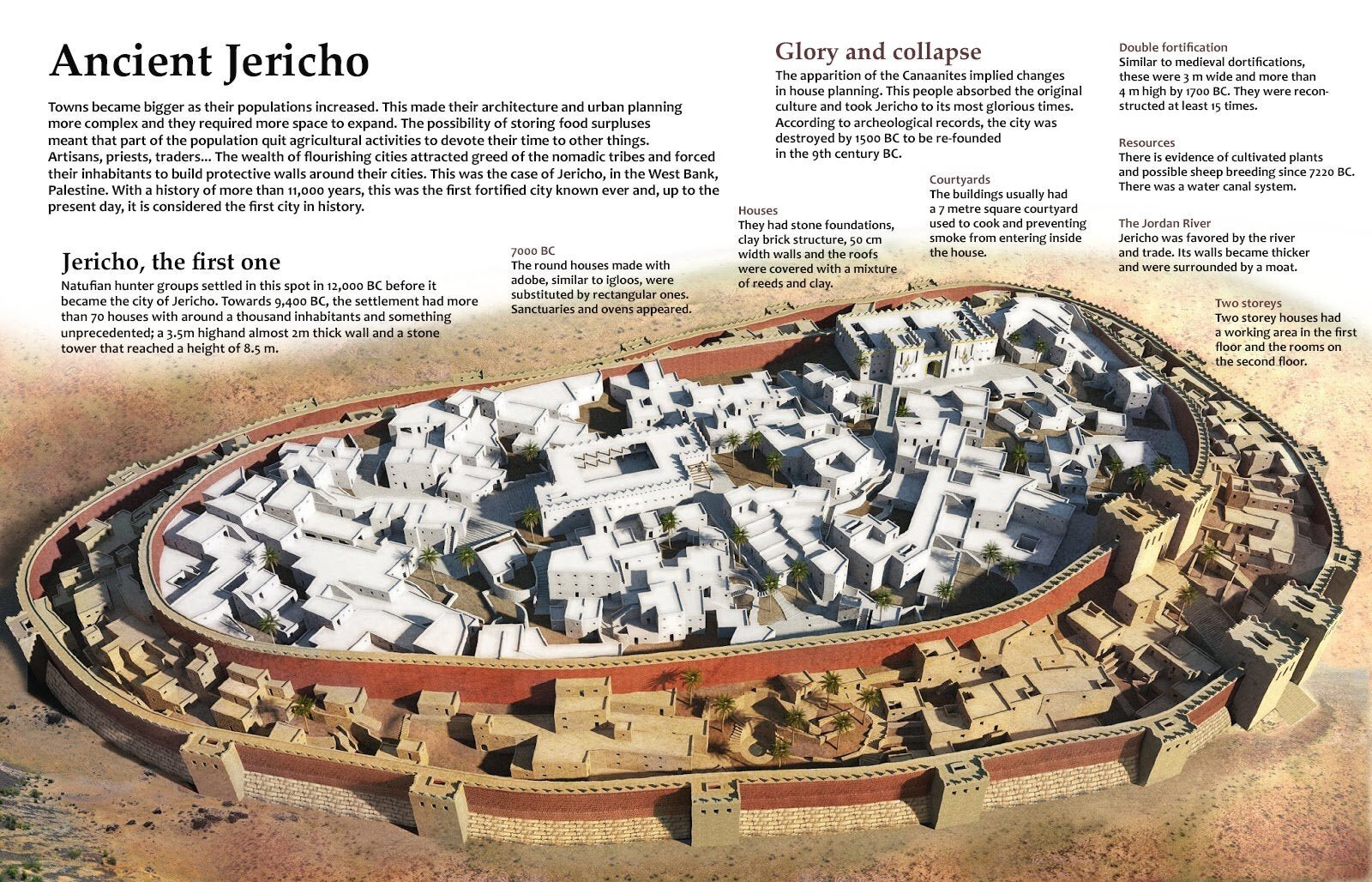

On the chronology of MB II B-C presently in vogue, that period is roughly-synchronous with the era of Hyksos domination in Egypt. As a consequence of this (the reason will be explained fully later), the pottery, fortifications, and scarabs from Palestine in this period have often been described as “Hyksos”. The fortified cities of MB II B-C Palestine are generally assumed to have been Hyksos strongholds, and are described as such by many leading authorities.

The end of the MBA in Palestine is marked by the fall of these cities and by the appearance of a pottery known as bichrome ware. The date for the appearance of this pottery in Palestine is dependent on the date given to the fall of the MB II cities. Archaeology has shown clearly that at the end of MB II C all the “Hyksos” cities were violently destroyed. It is commonly assumed that the cities were destroyed by Egyptian armies carrying out a war of retaliation against the Hyksos subsequent to the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt. The date of their destruction therefore depends on the date given to the expulsion of the Hyksos and the establishment of Egypt’s XVIIIth Dynasty. There is no firm agreement over the exact time of this event; dates traditionally given to it range between 1580 BC and 1550 BC, though slightly later dates have recently been proposed. Some of the. cities remained unoccupied for about a century after their destruction. Others were more quickly rebuilt.

The bichrome pottery which appeared in Palestine roughly at the time when the cities were destroyed, is generally considered a chief characteristic of the opening phase of the LBA. The LBA is viewed as extending through various phases to c. 1200 BC, when the transition. to the Iron Age occurred.

In the following pages the current view of the latter part of the MBA will be challenged and an alternative proposed. The main points made will be as follows:

- The MB II B-C cities of Palestine were not strongholds of the Hyksos, and their fortification-systems should not be described as Hyksos.

- The destruction of these cities was nothing to do with an Egyptian war of retaliation against the Hyksos; Egyptian action against the Hyksos probably never extended beyond Sharuhen, in the south of Palestine. .

- The destruction of the MB II cities has been incorrectly dated, because of its association with a hypothetical Egyptian offensive against the Hyksos throughout Palestine. Their destruction should be dated not to the 16th century BC but to the 15th. Consequently the appearance of bichrome ware and the beginning of the LBA must also be redated.

- The destruction of the MB II cities was the work of the Israelite tribes which left Egypt during the first half of the 15th century EC.

Each of these points will be argued in detail in the following pages. We will begin with a discussion of Jericho, in which the scheme outlined above will be applied to the problem. This will be followed by an Excursus on the chief methodological problem in Palestinian archaeology – that of formulating a reliable ceramic chronology. Then the new scheme will be discussed in relation to Hazor and the other cities mentioned in the Conquest narratives. The discussion of Jericho will bring out several points which are also valid for many of the other cities to be discussed, and will therefore serve to clear the ground for subsequent chapters.

2 The Problem of Jericho

2.1 Kenyon’s revisions of the views of Garstang

We will begin with an outline of Kenyon’s revision of the conclusions reached in the 1930’s by Garstang. Parts of what is said here will repeat material from Part One. Since it is not only convenient but necessary for a clear presentation of the problem, to have all the relevant material together in one chapter, this repetition is preferable to simply referring the reader to what has gone before.

In the 1930’s, Professor John Garstang’s excavations at Old Testament Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) unearthed what Garstang believed were remains of the city which fell to Joshua’s attack. Ruins of a double defensive wall, apparently broken down by an earthquake, were discovered in association with traces of extensive fire (sf. Garstang 1940133ff). This catastrophe marked the end of what Garstang called the Fourth City, or City D, and he dated the destruction to the beginning of the 14th century BC, “After 1400 and before 1385 B.C.” (ibid125). This date, as Garstang himself pointed out (ibid), fitted well with the date indicated for the Exodus by I Kgs 6:1, 480 years before the building of the temple; entering Palestine at the end of 40 years in the wilderness, the Israelites would reach Jericho around 1400 BC.

However, analysing Garstang’s published material in 1951, Kathleen Kenyon suggested several alterations to Garstang’s conclusions. She suggested that Jericho was not occupied at ail for tne 150 years before 1400 BC, that it only began to be re-occupied at that time after a period of abandonment (Kenyon 1951101-38). Her own subsequent excavations strengthened this conclusion. They also revealed that Garstang’s double wall had nothing to do with what he termed the Fourth City. This was revealed to be two walls dating from different times, but both belonging to the EBA (third millennium BC) and therefore not possibly related to Joshua’s attack (cf. Kenyon 1957170-71, 181).

Kenyon supposes that the Jericho destroyed by Joshua was a LBA town whose period of occupation she originally gave as c. 1400-1325 BC, though these dates have since been extended slightly (cf. Kenyon 197121-22). In other words, far from being destroyed around 1400 BC, Jericho was only just being rebuilt then.

Of this LBA town virtually nothing remains. Apart from certain items of pottery from the tell and in tombs, all Kenyon found of LBA date was “a row of stones”, identified as the foundations of the wall of a room, “a small irregular area of contemporary floor”, and on this “a small mud oven” and “a single dipper juglet” (Kenyon 1957261). It is concluded that erosion has removed all major traces of this town. Kenyon writes”It is a sad fact that of the town walls of the Late Bronze Age, within which period the attack by the Israelites must fall by any dating, not a trace remains” (ibid261-2).

Of the date of its downfall, Kenyon wrote in 1957″As concerns the date of the destruction of Jericho by the Israelites, all that can be said is that the latest Bronze Age occupation should, in my view, be dated to the third quarter of the fourteenth century B.C.” (ibid262; cf. also Kenyon 1970211). We should note, however, that Kenyon has more recently offered a slightly later date of “soon after 1300 B.C.” (197122). Since there is no notable trace of the town itself, there is, of course, no trace of any actual destruction.

2.2 Kenyon’s conclusions and the Exodus

How do these conclusions fit with the usual theories concerning the Exodus? The simple answer is that they do not fit at all. Kenyon’s conclusions dispose completely of an early date for the Exodus, unless the historicity of the Jericho tradition is denied altogether. According to Kenyon, there was no town on the site at all for the 150 years before 1400 BC, and no break in occupation for at least the next three-quarters of a century. On the other hand, her conclusions do not fit with the late date for the Exodus either. Kenyon herself points out that her date for the Israelite destruction suits neither the early nor the late date scheme, but offers no feasible solution to the problem thus created. At one point she writes that it must be admitted that it is not impossible that a yet later Late Bronze Age town may have been even more completely washed away than that which so meagrely survives. All that can be said is that there is no evidence at all of it in stray finds or in tombs” (1957262-3). But it is clearly not an idea which Kenyon favours. “The evidence seems to me”, she writes, “to be that the small fragment of a building which we have found is part of the kitchen of a Canaanite woman, who may have dropped the juglet beside the oven and fled at the sound of the trumpets of Joshua’s men” (ibid263).

Kenneth Kitchen, however, wishing to place the Exodus and the Conquest in the 13th century BC, adopts the suggestion that Joshua attacked a later town of which there is now no trace at all. Thus he writes”It is possible that in Joshua’s day (13th century BC) there was a small town on the east part of the mound, later wholly eroded away” (1962612). Elsewhere he cites Mycenaean pottery from the tombs as evidence for a settlement at Jericho in the 13th century (196663, n.22). Here he is following Albright (1963100, n.59), who claimed that the pottery from Tomb 13 at Jericho was definitely of 13th century date, but is contradicting Kenyon’s assessment and her assertion that no evidence for a later LBA town exists either in stray finds “or in tombs” (1957262-3).

In addition to the problem posed by Kenyon’s date for the fall of LBA Jericho, the fact that remains from this period are so scanty is itself a problem. The present writer is extremely suspicious of the fact that so little remains of what is supposed to have been the city attacked by Joshua. In order to increase the credibility of her view that this city has been almost completely eroded away, Kenyon points out that the major part of the populous MBA city has also vanished, being eroded during the period of abandonment (ibid261). However, many traces of the eroded MBA town, and especially of its destruction, were discovered by the excavators in the form of a layer of wash extending down the sides of the tell. In some places this wash of ash and silt was “about a metre thick” (ibid259-60; cf. 1970198). In other words, while large areas of the town were themselves removed by erosion, the products of this erosion are still preserved. But not even this much survives in the case of the LBA town.

This point is brought out strongly by the puzzlement expressed while Kenyon’s excavations were being carried out. Thus A.D. Tushingham wrote in a preliminary excavation report “But while the [LBA] walls themselves may have disappeared, the detritus of those walls would have washed down the slope and been discovered lower down the hill. But no trace of Late Bronze Age pottery has been found in this area throughout the whole extent of the trench [ Trench 1]. There is no evidence in Trench I for walls or strata of the Late Bronze Age” (195364). The following year, after two further trenches had been dug, the same writer reported”The two new trenches at the north and south ends, like Trench I on the west, have provided no evidence of Late Bronze Age city walls or debris from once-existent city walls. The mystery of the Canaanite city of Jericho which fell to Joshua is therefore as great as ever” (Tushingham 1954103, my emphasis). G.E. Wright also remarked at that time”The radical denudation of the site and the failure to find expected materials washed down the slopes of the mound are very puzzling facts indeed” (195367).

It seems particularly strange that there are no traces of any fortifications for the LBA town. Kenyon has suggested that perhaps the LBA occupants re-used the MBA rampart, of which sections were still extant in their day (1957262). Wright takes up this idea, but with little enthusiasm”If the settlement of Joshua’s time had a fortification wall at all, it would probably have been a re-use of the l6th-century bastion, though of such re-use there is no evidence” (1962a80; also earlier in 1953:64; cf. also Soggin 197285-6).

Wright’s own feeling is that “The Jericho of Joshua’s day may have been little more than a fort” (1962a80). Whence arose, then, the tradition of a city so large and formidable that a miracle was necessary to bring about its downfall? Wright says”… The memory of the great city which once stood there [i.e. in the MBA | undoubtedly influenced the manner in which the event was later related” (ibid). This is only a step away from Noth’s view (e.g. 1960149, n.2), which is followed by Gray (196293-4), that the story of Jericho’s fall is an aetiological legend, and that there never was an Israelite attack as described in Jos 6, a view which the present writer feels is inadequate to account for the growth of a tradition which now occupies over fifty verses of narrative (Jos 2:1-24;513-627, – in contrast to merely two verses taken up by the conquest of each of the six cities mentioned in Jos 10:28-39). Wright himself describes his own remarks as “nothing more than suggestions” and concludes”… At the moment we must confess a complete inability to explain the origin of the Jericho tradition” (1962a80).

We may conclude this part of our discussion by quoting one of Kenyon’s more recent statements on the problem”It is impossible to associate the destruction of Jericho with such a date [as is required by a 13th century Exodus | . The town may have been destroyed by one of the other Hebrew groups, the history of whose infiltration is, as generally recognized, complex. Alternatively the placing at Jericho of a dramatic siege and capture may be an aetiological explanation of a ruined city. Archaeology cannot provide the answer” (1967273).

2.3 A search for an explanation

Various efforts have been made to account for the lack of support which the archaeology of Jericho appears to give to the biblical account of its destruction, without denying the basic historicity of the account.

The most radical suggestion is that of~C. Umhau Wolf (196642-51), who proposes that Tell es-Sultan may not be the site of Jericho at all, but of Gilgal, and that Jericho must therefore be sought elsewhere (cf. Franken 19766). The present writer does not feel that any compelling reasons exist for doubting the identification of Tell es-Sultan with Old Testament Jericho.

R. North has raised the possibility that the Jericho attacked by Joshua actually lay near Tell es-Sultan but was not identical with it (1967b70), and E. Yamauchi has suggested that “since the excavations by Sellin, Garstang and Kenyon have not exhausted the eight-acre site, future excavations may still unearth the missing Late Bronze remains (197353).

Such suggestions are possibilities, but belong more to the realm of wishful thinking than to that of constructive reasoning built on existing knowledge. A less desperate expedient would be more welcome.

Two writers have recently attempted to reinterpret the existing archaeological evidence in such a way as to allow for an attack on Jericho by Israelite forces under Joshua around 1400 BC.

L.T. Wood, in an article which appeared in 1970, argues for a return to Garstang’s conclusions on certain key points. He does not challenge Kenyon’s redating of Garstang’s “double wall”, but argues that this makes no difference to Garstang’s other conclusions”The section of the wrongly dated wall found is far removed from the area where he located his significant material, the evidence from which has no necessary connection with the wall and is not lessened in value because of its redating” (Wood 197071).

The material which Wood considers to be pivotal is “pottery found on both the mound above the spring and in the tombs which Garstang contends represents occupancy until ca. 1400 B.C., but which Miss Kenyon says terminated before 1500 B.C.” (ibid72). It is here that the evidence is most crucial for Wood’s arguments, yet it is sadly also at this point that Wood loses touch with the published material and betrays a serious misunderstanding of it. The pottery to which he refers in the sentence just quoted is not assigned by Kenyon to the occupancy which she believes terminated in the 16th century BC; it is assigned in fact to the 14th century (cf. Kenyon 1951120-121,130-33; 1957261). Furthermore, Wood associates this pottery with a burned layer which he wishes to argue is the result of Joshua’s destruction of the city, in contrast to Kenyon who ascribes this burned layer to the “Egyptian” attack on the city at the end of the MBA (cf. Wood, 72). It is questionable, however, whether any of this pottery should be associated with the destruction layer. Kenyon’s discussion (1951130-33) appears to treat it as chronologically quite distinct, and Wood himself describes the layer of ash as lying below the pottery, whereas one would expect the ash to overlie the pottery if the pottery really belonged to the occupation period whose termination the ash indicates. This means that Wood’s arguments for dating this pottery (he refers especially to Cypriote items) to a period after 1500 BC (Wood, 72-3) have no bearing on the date of the destruction layer.

The basic weakness of Wood’s argument is that while it takes account of some of the ways in which Kenyon’s discoveries modify Garstang’s conclusions, it fails to acknowledge other modifications which are required, particularly concerning the relationships between the various strata uncovered by Garstang’s excavations at different-parts of the tell.

B.K. Waltke, in an article which appeared in19/2, also bases his reassessment of Kenyon’s conclusions on the pottery discussed by Wood, but frames his argument somewhat differently. He points out that in Kenyon’s 1951 discussion, she dated the pottery “from the upper level above the ruins of the /MBA] store rooms” to the first half of the 14th century BC (cf. Kenyon 1951:121, 130-33), and that she has not yet made any statement modifying this conclusion. Waltke therefore states”In a word, according to Kenyon, the latest burnt debris from the Late Bronze Age city cannot be dated later than mid-fourteenth century B.C.” (197240).

Waltke’s intention is to argue that the occupation of the tell in the LBA began some time before 1400-BC and ceased during the first quarter of the 14th century, this break being the result of the Israelite Conquest. To this end he tries to confine the LBA pottery from the tell to the first half of the 14th century and to use it to date the burnt layer. He deals with pottery from some of the tombs, which he acknowledges must be dated later than 1350 BC, by assigning it to a period of sporadic habitation at the time of Eglon, king of Moab (cf. Jdg 313).

There is a non sequitur in Waltke’s argument similar to the one introduced by Wood, namely the assumption that the pottery gives a date to the burnt debris. Nowhere does Kenyon treat the burnt layer as deriving from the LBA city, and while her 1951 article is sometimes not very clear on this point, in her works published after her own excavations at the tell it is quite apparent.

In addition, it is doubtful whether Kenyon’s 1951 statements concerning the date of the LBA pottery can be held to contradict her later conclusions that the LBA city was destroyed c. 1325 BC. Kenyon did in fact state in 1951 that this LBA pottery from Jericho may “just overlap” with that from Stratum VIII at Beth-shan, dated to the second half of the 14th century (1951121); in other words, while believing that this LBA pottery from Jericho should be assigned chiefly to the first half of that century, she was leaving open the possibility of a slight extension of the period which it represented into the second half of that century.

There is no real contradiction between this and her later (1957) statement that “… The latest Bronze Age occupation should, in my view, be dated to the third quarter of the fourteenth century B.C.” In asserting that the latest pottery from Tombs 4, 5, and 13 should be dated to the second half of the 14th century, and that it should be linked with Eglon’s temporary occupation of the site (mentioned in Jdg 313), Waltke is in fact adopting one of Garstang’s conclusions (1940124, 127-8). Kenyon on the other hand sees this pottery as quite in keeping with a Canaanite occupation of the tell from c. 1400 BC down to c. 1325 BC (1957261) or c. 1300 BC (197122) for support for his case. He argues that this building must post-date the burnt layer (which, as we have seen, he erroneously dates to the first quarter of the 14th century), and is therefore evidence of some sort of occupation subsequent to the Israelite destruction of the city. “If then a substantial building such as the Middle Building was secondarily introduced on the tell after the destruction … one has good reason to think that the few recognisably late pottery examples from the tombs belong to this occupation and cannot be used to date the Conquest” (197242).

Waltke appeals to a structure known as the Middle Building Apart from the fact that this argument incorporates the error already noted concerning the burnt layer, it also hinges on the dating of the so-called Middle Building, which is itself notoriously difficult. No ceramic evidence has been published from the building itself (Kenyon 1957261), and the evidence from stratigraphy is uncertain. Thus Kenyon appears to have changed her mind concerning the date of the building, first treating it as later than its foundational material (1951120), but subsequently suggesting that the debris beneath the building May indicate the date of the building itself (1957261).

Since there is no certain way of dating this building, it cannot be used in the way Waltke wishes. The building may radically post-date the latest pottery from the tombs, and could perhaps even date from the time of David, since from II Sam 105 it would appear that there was some sort of occupation at Jericho at that time.

Waltke (197240-41) and Wood (197072) both appeal to the evidence of Egyptian scarabs from the Jericho tombs for support for the view that occupation of the tell continued through most of the 15th century and ceased soon after 1400 BC. The series of XVIIIth Dynasty scarabs found at Jericho were one of Garstang’s main pieces of evidence for a date between 1400 and 1385 BC for the end of the Canaanite city (cf. Garstang 1940120). This series, which consists of scarabs from the reigns of Hatshepsut, Thutmosis III and Amenhotep III, comes to an end with the reign of the latter pharaoh; no objects datable to the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) have been found at Jericho. Furthermore, the city is not referred to in the Amarna letters, which date mostly from Akhenaten’s reign, a fact which Garstang considered as further evidence for Jericho’s destruction before 1385 BC, the date after which the bulk of the letters were written (cf. Garstang 1940:122).

As far as the scarabs are concerned, the present writer feels that Kenyon’s scepticism of the value of these objects for dating is perfectly justified; as she points.out, scarabs are the kinds of objects which are quite likely to become heirlooms, and they cannot be relied upon to date the strata or the tombs in which they are found except by providing an upper limit (cf. Kenyon 1951116-17; 1957260).

The silence of the Amarna correspondence concerning Jericho is perhaps a more telling point against Kenyon’s view of an occupation which spanned the Amarna period. This silence will be accounted for in the scheme presented below. It does not offer much support to the theories of Wood or Waltke, however, since neither of them offers evidence for an occupation at Jericho before the Amarna period. It is obviously not possible to make out a compelling case for a destruction at Jericho shortly after 1400 BC without presenting evidence for an occupation of the site prior to that time, and this both writers fail to do.

Not only are the scarabs dubious evidence; there is very little pottery which can without question be dated before 1400 BC. There is therefore insufficient evidence from both pottery and scarabs for the assumption that a city existed at Jericho in the 15th century /4/. More important still, neither Waltke’s theory nor that of Wood attempts to attribute any buildings or fortifications to the city supposedly destroyed by Joshua. In other words, after all their theorizing, the LBA city itself still avoids detection. Waltke says nothing about this problem, while Wood simply agrees with Kenyon’s conclusion that “The city mound was severely denuded of all remains of Late Bronze occupancy (i.e. after 1500 B.C.) except on the mound above the spring” (Wood 197070-71), a view which we have already seen to be inadequate to account for the lack of remains.

Therefore, even if the theories of Wood and Waltke did not contain erroneous assumptions, they would still leave the most pressing problem untouched, that problem being the almost complete absence of building remains from the LBA.

3 The Proposed Solution

3.1 An Alternative viewJoshua and the end of MBA Jericho

In view of the complete failure of all attempts made thus far to resolve the problem of our “complete inability to explain the origin of the Jericho tradition” (Wright 1962a80), there is perhaps good reason to question whether the Israelite attack was directed against a LBA Jericho at all. Could it have been an earlier phase of the city which fell to Joshua’s attack?

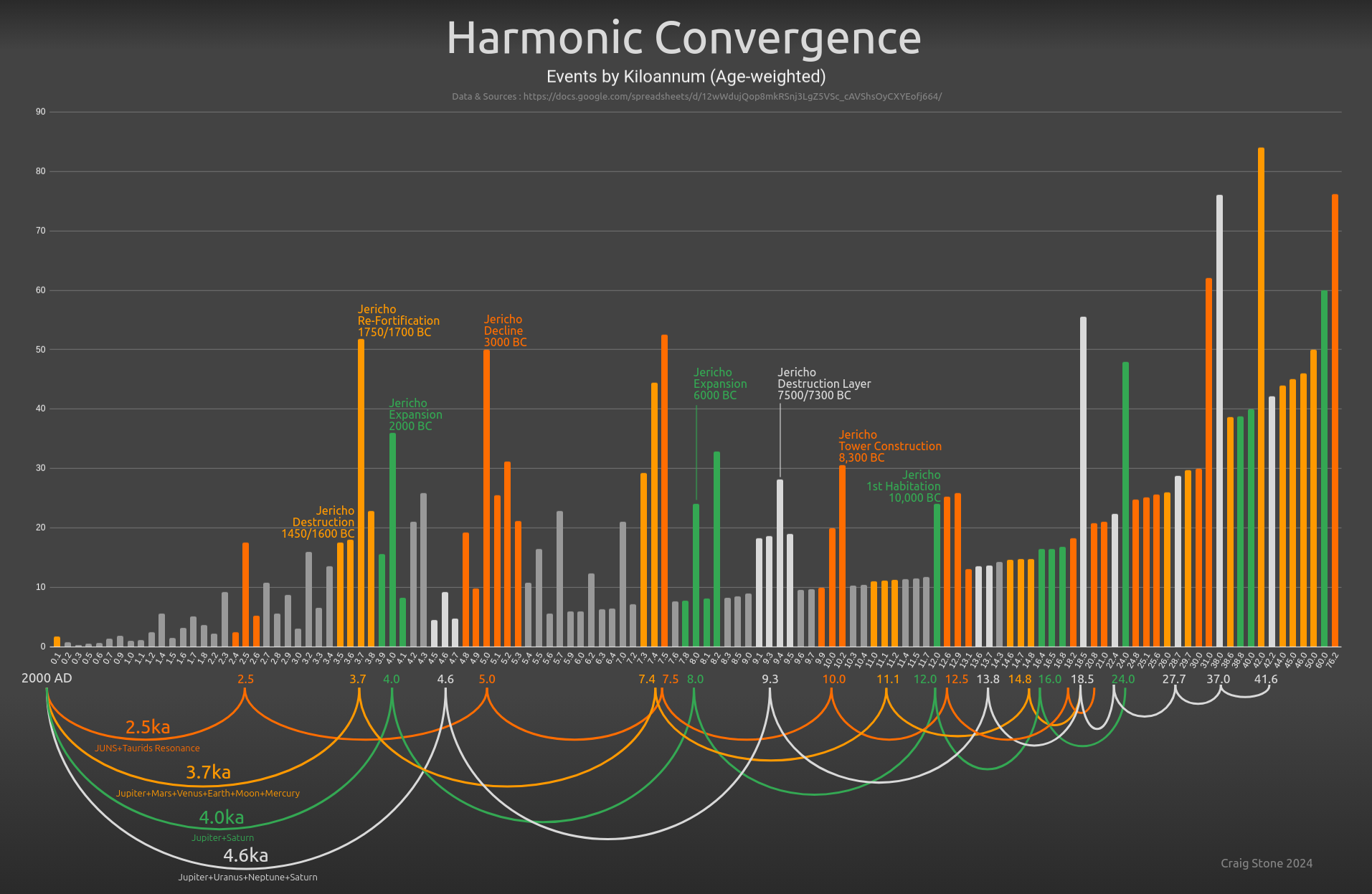

The various Bronze Age phases of Jericho are dated by Kenyon as follows. The EBA phase began around 3000 BC and ended shortly before 2000 BC when the city apparently fell during an invasion by hostile groups. In the following period (Intermediate EB-MB in Kenyon’s terminology, MB I in Albright’s) the tell was occupied by semi-nomadic tribesmen whom Kenyon suggests were Amorites. Around 1900 BC the city was rebuilt and the MBA period beyan (i.e. in Kenyon’s terminology; in Albright’s terminology this is the beginning of MB II A). During this period the city became populous and was heavily fortified with a new style of defensive system. This period ended in the first half of the 16th century BC, the city being once more destroyed in an enemy attack. This destruction was followed by a period of abandonment, and then at about 1400 BC we supposedly have the beginnings of the problematical LBA city which we have just been discussing.

Prior to the LBA, therefore, Jericho had fallen before an attacking enemy on at least two occasions. Could either of these two destructions be attributed to Joshua? In the revolutionary theory of D.A. Courville (1971) dates for all archaeological periods in Palestine are lowered by over six centuries, and the destruction of EBA Jericho is attributed to Joshua’s attack, which Courville dates to c. 1400 BC. However, Courville’s scheme depends on a revision of Egyptian chronology which, even granting that certain presuppositions underlying the present Egyptian chronology may be at fault, does not seem workable to the present writer. Even within its own framework, Courville’s theory concerning the Conquest contains serious inadequacies. The destruction which ended the EBA must therefore be ruled out. What of that which ended the MBA?

Kenyon sometimes gives the time of this destruction as c. 1580 BC (1970194), sometimes as c. 1560 BC (1956552-555;1967272), and at one point’ says MBA Jericho was destroyed “somewhere in the period 1580-1550 B.c.” (1951117). Her reasons for this dating will be discussed in detail below.

If Kenyon had given dates a century-and-a-half later for the end of the MBA city, we would have no hesitation (working with the early date for the Exodus) in ascribing this destruction to Joshua’s attack. The archaeological evidence concerning the catastrophic end of this phase of the city provides parallels with the biblical narrative at several points.

Sometime during the MBA (about 1750/1700 BC according to current views), the defences of the city were strengthened by the addition of a huge artificial embankment running all the way round the city. This defensive system was the one in use when the MBA city finally fell. It consisted of “a wall crowning a great artificial bank, retained at a slope considerably steeper than the natural angle of the rest of the soil by a plastered surface and a massive revetment wall at the base” (Kenyon 1957:220). All this “must have been a most imposing defence, somewhat resembling from the outside the defences of a great medieval castle” (ibid216). This strongly fortified city was “certainly populous” (ibid). In short, it would fit excellently as the large walled city which the biblical narrative says Joshua faced on crossing the Jordan.

Moreover, the enemy which attacked this city finally destroyed it by setting it on fire. Kenyon writes”… The evidence for the destruction is … dramatic. All the Middle Bronze Age buildings were violently destroyed by fire…. This destruction covers the whole area, about 52 metres by 22 metres, in which the buildings of this period surviving the subsequent denudation have been excavated. That the destruction extended right up the slopes of the mound is shown by the fact that the tops of the wall-~stumps are covered by a layer about a metre thick of washed debris, coloured brown, black and red by the burnt material it contains; this material is clearly derived from burnt buildings farther up the mound” (1970197-8). “Walls and floors are hardened and blackened, burnt debris and beams from the upper storeys fill the rooms, and the whole is covered by a wash from burnt walls…” (1966a17). “… There is no doubt from the scorched surfaces of the walls and floors of the violence of the conflagration” (1957232; cf. Garstang 1940104). Kenyon is certain that this burning was the result of a military campaign against the city (1957229; 1970194-7; cf. Garstang 1940:103-4). We are forcibly reminded of the fact that Joshua had Jericho burnt to the ground after he had taken it (Jos 624).

It may be objected that in the biblical account it is related that the wall of the city “fell down flat” (Jos 620), while in some places the defences of the MBA city are well preserved, and the summit of the rampart actually survives in at least one place. However, the biblical account does not say that the entire city wall collapsed. Indeed in Jos 6:22, two verses after it is stated that the wall fell down flat, we find Joshua sending the two men who had formerly spied out the city to enter Rahab’s house and bring her out; since we have previously been told (Jos 2:15) that Rahab’s house “was built into the city wall, so that she dwelt in the wall”, it is clear that the account envisages that at least one section of the wall remained more or less intact after the disaster. The account in Jos 6 is saying simply that in some places breaches appeared in the defences so that Joshua’s army was able to enter the city.

An event which could cause sections of the defences to collapse suddenly is not difficult to find. It is a fact that Jericho lies on a volcanic rift at the northern end of a geological fault which passes all the way along the Jordan Valley, continuing south through the Arabah and the Red Sea, and on into Central Africa (cf. Garstang 1940160). As Garstang pointed out, the zone in which Jericho lies “is never wholly free from earthquake shocks” (ibid135), and earthquakes at Jericho are well attested in both ancient and modern times by archaeological evidence and written records respectively (ibid:136; cf. Kenyon 1957:175-6, 262).

We will return shortly to the probability that a great deal of seismic activity occurred along the Arabah and the Jordan Valley during the period of the wilderness journeys and the beginning of the Conquest. First I wish to direct attention to Num 25, for here begins a series of three events which are strikingly evidenced in the biblical narrative and the archaeological record alike.

In Num 25 we find the Israelites encamped at Shittim, “in the plains of Moab beyond the Jordan at Jericho” (Num 221; cf.3348-9); i.e. the Israelite camp extended along the eastern side of the Jordan just opposite the city. The period spent at Shittim immediately preceded the attempt to destroy Jericho. It was from there that spies were sent to the city by Joshua (Jos 2:1), and from there that the Israelites finally set out to attack it (Jos 3:1). We read that while the camp was there, the area was affected by a severe plague. Num 259 tells us that 24,000 Israelites died of this plague.

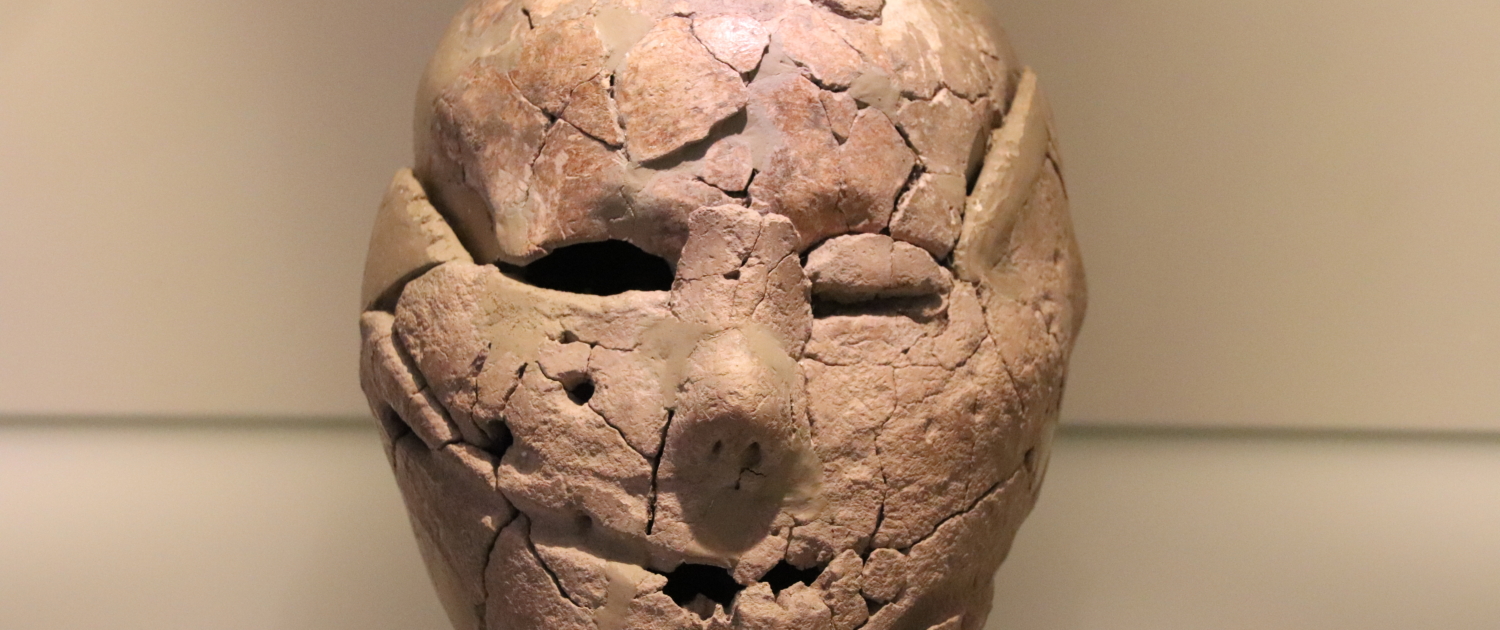

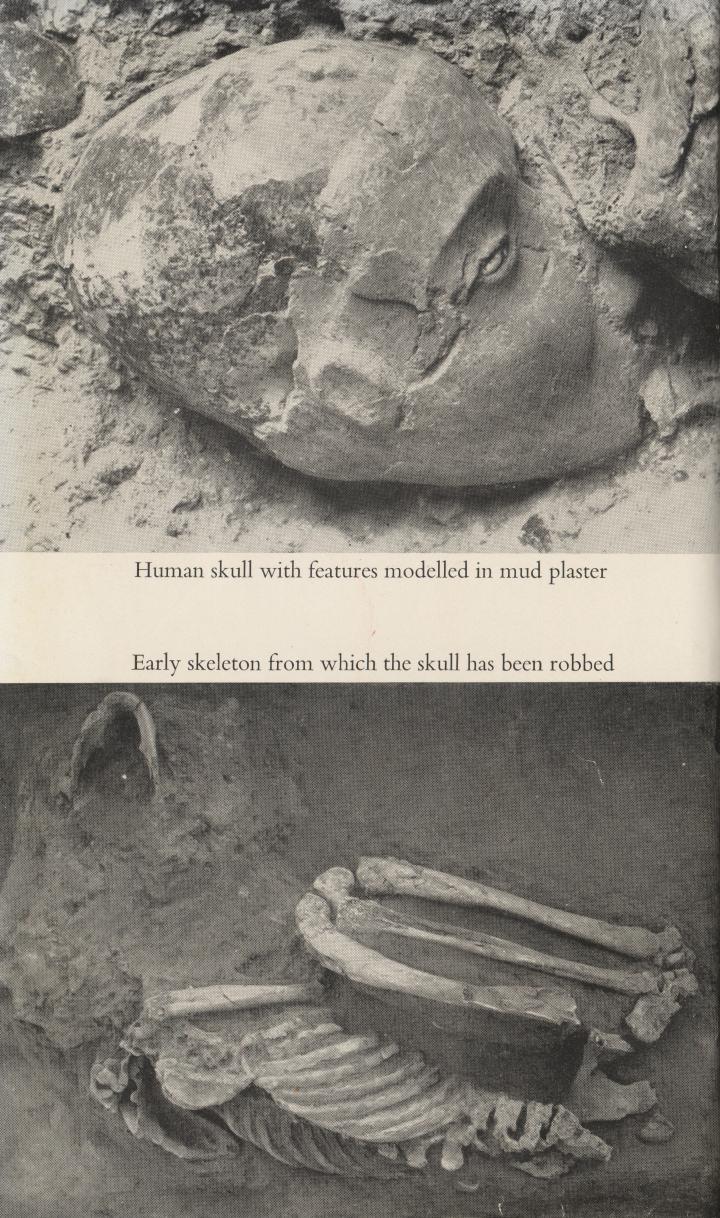

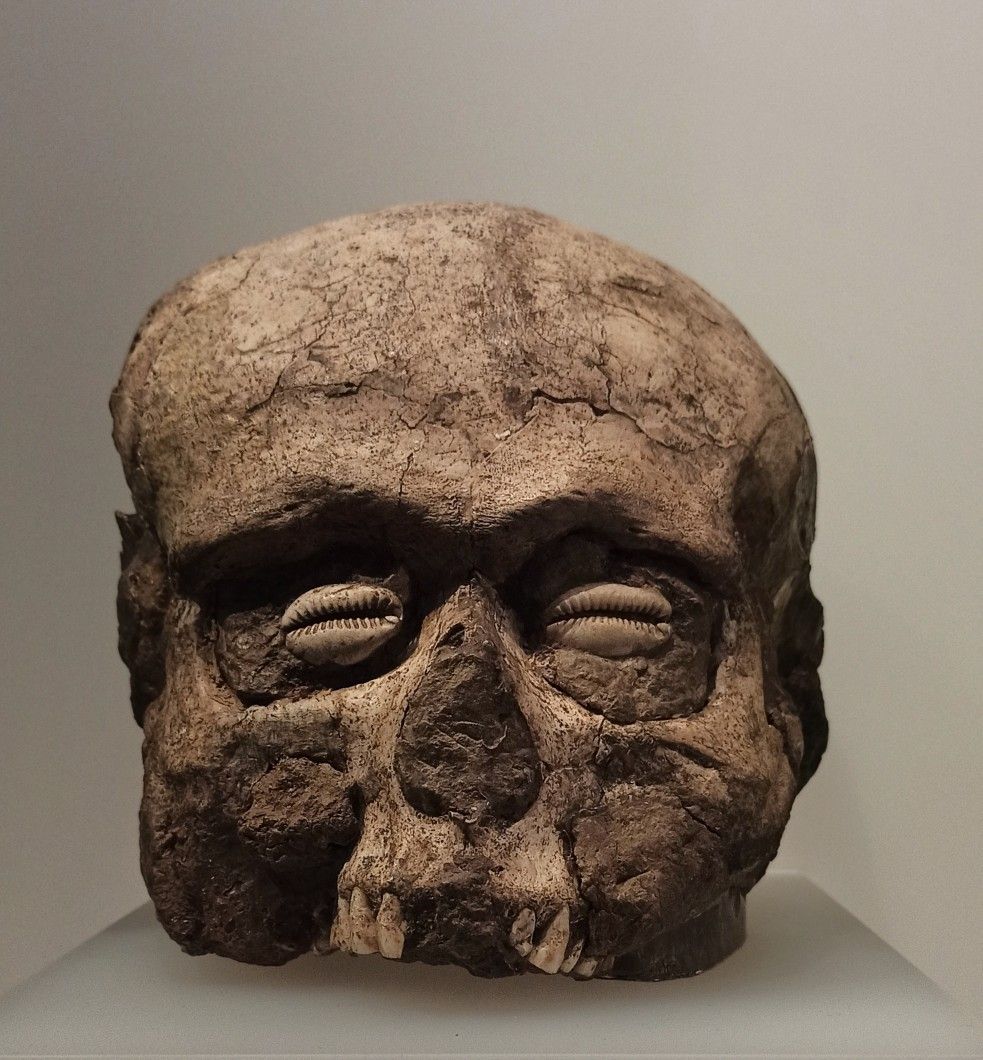

It is remarkable that a plague is evidenced at Jericho shortly before the end of the MBA city. Late in the sequence of MBA tombs at Jericho, there are several examples of multiple burials. Such burials are not a usual feature of the MBA city, and Kenyon says we may infer from them “that some catastrophe caused high mortality on an occasion very late in the history of Middle Bronze Age Jericho” (1957254). Since there are no signs of injury to the bodies, enemy action is not a likely cause of these deaths. Famine is ruled out by the lavish provision of food in the tombs. Kenyon therefore concludes that MBA Jericho “suffered a plague” shortly before the greater catastrophe of the city’s destruction (ibid255).

Next we turn to the collapse of the city’s walls in Jos 6:20. Garstang wrote that “Only the miracle of an earthquake shock will justify the description of this event in the Book of Joshua” (1940175, cf. 135), and underlined the likelihood of this explanation by referring to numerous examples of earthquakes, ancient and recent, in the Jericho region. Further, his son, J.B.E. Garstang, collected together various biblical references which he considered indicate a series of instances of seismic activity at the time of the Exodus, the wilderness journeys, and the Conquest. He suggests that “at the time of the Exodus the whole of the geological two-fold rift from Palestine to Lake Nyasa was in a state of violent seismic and volcanic upheaval” (ibid160). Thus he suggests that certain of the plagues of Egypt are accounted for by volcanic activity affecting the sources of the Nile and areas further north, to the east of the Red Sea, producing clouds of ash which darkened the air. The pillar of fire and smoke may have been “a column of dust and steam and ash from the open mouth of an active volcano”, and earthquake activity may have been responsible for the drawing back of the water at the sea of passage; as for the events at Sinai, “Who can read the narrative (Ex. 1916-19) without realising that it describes perfectly the terrific convulsions of a volcano?” (ibid163).

Further examples of seismic activity are the opening of the earth to swallow the rebellious host in Num 1627-35, and the event which temporarily stopped the flow of the Jordan in Jos 314-17 (cf. ibid165-171, and on the latter incident also 136-7).

Garstang believed he had unearthed archaeological evidence of the earthquake recorded in the biblical narrative, in the form of fissures and dislocations in what he believed to be the walls of the city attacked by Joshua (ibid135-6). These, however, are the walls now assigned to the third millennium BC.

Does any evidence exist for an earthquake having occurred at the end of the MBA city?

Such evidence comes not from fissured walls but from discoveries made in certain of the tombs of MBA Jericho. The tombs concerned are those containing the multiple burials. In these tombs the organic material shows a remarkable degree of preservation compared with that shown by material deposited in the EBA and earlier MBA tombs. In the earlier tombs, “The small total amount of organic matter … disintegrated more or less completely. In contrast to this condition, the multiple burials in the MB tombs were accompanied by a wealth of mortuary equipment comprising pottery, wood, matting, basketry and food, wig-materials and textiles. Roast meat is commonly preserved, and parts of the skin and flesh of the human bodies, and occasionally hair, are preserved. The brain is very often found in the skull in a shrivelled condition” (Zeuner 1955125).

F.E. Zeuner, whose words these are, made a detailed study of three tombs, J14, 319, and J20, in an attempt to account for this remarkable degree of preservation. Zeuner concluded that the organic material was preserved because some while after the burials were made, natural gas containing methane and carbon dioxide entered the tombs and brought both bacterial decomposition and termite activity to an end (ibid128). Earth movement and resultant fissuring are suggested as the best explanation of how this gas was suddenly released into the tombs (cf. S. Dorrell 1965706; Kenyon 1957250). It is therefore significant that J14 and J20 were both found to have suffered heavy rock falls (Zeuner 1955125), and Kenyon writes that “One can see in the walls of the tomb shafts and chambers how the rock has been twisted and fractured” (1957250).

When we recall that Kenyon dates the multipie burials to shortly before the destruction of the city, and that the process of decomposition had only just begun when it was brought to a standstill, it becomes very probable that the earthquake activity which released the natural gas into the tombs occurred roughly at the time of the city’s final collapse.

The third correspondence between the biblical narrative and the archaeological record has already noted the deliberate destruction of the city by fire.

Thus the biblical narrative and the archaeological finds at MBA Jericho point to the same pattern of events. The archaeological evidence implies a plague, followed shortly by earthquake activity and the total destruction of the city by burning. The biblical narrative gives the Same sequence: a plague in the Jericho region, followed not long after by what may readily be interpreted as at least two instances of seismic activity (the first stopping the Jordan, the second destroying the city walls), followed by conquest of the city and its eventual destruction by fire.

The evidence for linking the biblical narrative with the end of the MBA city is therefore very striking. But all this remains nothing more than interesting speculation unless we can show that it is permissible to move the end of MBA Jericho from the 13th century BC into the 15th. We will now examine the reasons for the generally accepted 16th century date. There are in fact only two reasons for this date. They will be examined in turn.

3.2 Jericho and the expulsion of the Hyksos

One reason for the date currently accepted for the end of MBA Jericho has its roots in the city’s assumed link with the Hyksos.

Kenyon and Garstang both connect the destruction of the MBA city with the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt. This event is dated variously between 1580 and 1550 BC, though some writers have offered a slightly later date, and Garstang tended to use a round figure of c. 1600 BC when referring to it (cf. Garstang 1940104).

It is known that when Egyptian armies under Amosis, founder of the XVIIIth Dynasty, drove the Hyksos out of their capital Avaris, they pursued them into Palestine. Sharuhen (Tell Far‘¢ah), in the extreme south of Palestine, was occupied by the retreating Hyksos and was subsequently besieged by the Egyptian armies. It fell after three years (cf. Pritchard 1955233).

Kenyon, like Garstang before her, supposes MBA Jericho to have been a Hyksos stronghold and therefore one of the main targets in an Egyptian campaign of liberation and revenge which destroyed all the Hyksos cities of Palestine. Thus, writing of the end of MBA Jericho, Kenyon has stated”This destruction can be identified with very little doubt as the work of the Egyptians” (1957229; cf. 1951117; 1970195-7; also Garstang 1940103-4).

Two points need to be noted. The first is that there is no evidence whatever for an Egyptian war of retaliation in Palestine. There is no evidence that the Egyptians continued their pursuit of the Hyksos beyond Sharuhen (cf. Epstein 1966171). Indeed, evidence suggests that as soon as Sharuhen had fallen, Amosis turned his armies southward in an attempt to regain control of Lower Nubia (cf. Sdve-S&derbergh 195171). It may reasonably be asked how we can possibly envisage Egypt launching a campaign which successfully destroyed almost every large city in Palestine, when it took the Egyptians three years to reduce the Hyksos garrison nearest to their own country. In short, the whole notion of an Egyptian campaign against the Hyksos extending throughout the whole of Palestine is both improbable and largely unsupported by evidence.

We may pause to ask how the notion arose that Amosis led a massive drive into Palestine after the fall of Sharuhen. The idea originated early (e.g. Breasted 1906b227) as a result of an over-interpretation of a text left by one Amosis-Pennekheb, stating that he campaigned with the pharaoh Amosis in Djahy. Djahy is sometimes said to have been a geographical term used to refer to central Syria and Palestine, but according to M.S. Drower it meant the coastal plan of Phoenicia (1973245). Drower comments on this campaign by Amosis~Pennekheb”… We are given no indication of the whereabouts or extent of the operation” (ibid431). Further support for a campaign into Palestine has been drawn from a reference in a text from late in the reign of Amosis, to the use of oxen which came from “the land of the Fenkhu” in the quarries of El-Masara. Again, according to Drower, the geographical term means the Lebanese coast (ibid425).

In any case, T.G.H. James comments”unfortunately an uncertainty in the reading of this text makes it doubtful whether the oxen were captured in a campaign or supplied as tribute by the Asiatics” (19659).

It is amazing that a theory based on such meagre evidence should have become so widely accepted and even taken for granted. It is unlikely that it would have been so generally adopted if the destruction of Palestine’s MBA cities had not been interpreted as evidence of Amosis’ hypothetical activities. But the fall of Palestine’s MBA cities has now become the mainstay of the theory. Thus a circular argument has been produced which loses sight of the fact that the above texts supply no evidence at all fora campaign into Palestine itself.

The second point is this: there is no reason to believe that MBA Jericho was a Hyksos fortress. If Jericho was not occupied by the Hyksos, there is no reason for attributing its destruction to an Egyptian army or for linking it at all with the political situation of the 16th century BC. One reason for dating Jericho’s destruction to that century thus disappears.

Garstang was confident that Jericho was a Hyksos stronghold in the MBA. He describes pottery from this period as “examples of Hyksos art”, and a diagram of a MBA tomb is labelled as a “section of a Hyksos tomb” (Garstang 194099). He even writes of storage vessels sealed “in numerous instances with the signet of a Hyksos ruler” (ibid94), and of finding the scarabs of Hyksos kings (ibid94-5, 101-3).

All this is inference and assumption. Jericho has not yielded a single item which can truly be identified as Hyksos.

In point of fact, the great majority of scarabs from MBA sites in Palestine are local products, and Kenyon describes them as “rather distant relatives” of the Egyptian scarab, bearing only “crude and meaningless copies of Egyptian hieroglyphs” (1957:253; cf. 1970193). The scarabs from Jericho are no exception to this general rule. A detailed discussion of scarabs from Jericho, by D. Kirkbride, constitutes Appendix E of the detailed excavation report. Here we learn that of the multitude of MBA scarabs discovered during Kenyon’s excavations, only three bear royal titles, and only one of those discovered during Garstang’s excavations bears a royal title (Kirkbride 1965580, 592). Three of these four names definitely belong to non-Hyksos kings, while the fourth belongs to no known ruler, Hyksos or otherwise (ibid583).

Kenyon has attacked the practice of describing finds from MBA Palestine as Hyksos in the following words “Within MB II falls the period of the Hyksos in Egypt. Such importance has been attached to this that the period in Palestine is sometimes given the overall name of Hyksos and the pottery and other objects typical of this stage designated specifically Hyksos. This is incorrect…”. There is “cultural continuity from MBI to MB II” and a “cultural continuum at this period from north to south on the Syrian littoral…. Unless this whole new culture is to be ascribed to the Hyksos, none of it is Hyksos” (1966a14-15; the point is also made by Van Seters, 19663). And yet Kenyon herself has assumed a Hyksos occupation for the second half of the MBA at Jericho. The reason for this is that the defensive system of the period – the wall crowning the artificial bank with a revetment wall at the base – is commonly associated with Hyksos influence.

Examples of this type of defensive system appear in various other places during the MBA, and Kenyon has associated their appearance with the spread of the Hyksos (1957220-28; 1966a:39; 1966b65-73; 1967269; 1970193). She says”The distribution of the new type of defences shows that this is the material evidence of the Hyksos period in Palestine. Defences of this type can be traced from Carchemish in the north-east through inland Syria and Palestine to Tell el-Yahudiyah north of Cairo” (1966a39; cf. map in 1966b70).

This theory is dependent on the view that the Hyksos contained Hurrian elements which entered Palestine from the north. The Hurri were “a people of Indo-European origin who established themselves on the Middle Euphrates about the beginning of the second millennium and built up the kingdom of Mitanni…. In the course of the next centuries there was a steady expansion of Hurrian influence towards the Meditteranean coast…” (Kenyon 1957:222). It is suggested that by the 18th century BC a number of towns in Syria-Palestine were under the control of Hurrian bands from the north, and that these people became “a ruling warrior aristocracy” whose members imposed their methods of warfare on the land and were responsible for the defensive systems of the MBII (Kenyon’s terminology) period (ibid223). These same warrior groups penetrated into Egypt and contributed to the overthrow of the Middle Kingdom; “… To the Egyptians they were known as the Hyksos, foreigners, Asiatics” (ibid224).

However, this view of the origin and spread of the Hyksos has been undermined in so many ways in recent years that it is now hardly tenable.

The notion that Hurrians constituted a major part of the people which took control of Egypt has been shown to be without firm foundation. Van Seters concludes an examination of onomastic evidence from Egypt by saying that “not a single name of this period can be identified with certainty as Hurrian” (1966183). Van Seters concludes that the Hyksos were Amurrite princes from the Levant (ibid190), and denies any connection between the Hyksos and the MBA defences (ibid32-3).

There is in fact no evidence at all for the notion of a Hurrian movement into Palestine from the north in the 18th-17th centuries. As Van Seters points out, Hurrians are mentioned for the first time in the annals of Thusmosis III and Amenhotep II (15th century), and the term “land of Hurru” as a designation for Syria-Palestine “cannot be dated to much before the Amarna Age” (ibid186). As Redford says, “No evidence … either archaeological or epigraphic, suggests the presence of an important Hurrian element in the Levant until the sixteenth century; and then it appears, not in the form of a Vélkerwanderung, but as a state ensconced beyond the Euphrates” (1970b6-7; cf. Van Seters 1966187).

One argument in favour of a Hurrian element among the Hyksos has for a long time been that the Hyksos introduced the horse and chariot into Egypt. (The Hurrian state of Mitanni appears to have been one of the main centres of the domestication of the horse). However, Van Seters has shown that evidence for the Hyksos having possessed the horse and chariot is indecisive (1966185). Sdve-S&8derbergh has made a similar point”… There is not the slightest evidence that the Hyksos used the horse until the very latest part of their rule in Egypt….. Everything in the evidence seems to demonstrate that the Hyksos never used this war technique until possibly in the last struggles against the Egyptians before they were expelled from the country” (195159-60). The same writer has also made strong criticisms of the assumption that ramp fortifications of the type found at Jericho were introduced by the Hyksos. He points out that “no certain instance [of this fortification type | is known from Egypt, the only country where the actual Hyksos are established with certainty as a political factor!” (ibid60). Two ruins in Egypt, at Tell el-Yahudiyah and Heliopolis, have often been interpreted as examples of such fortresses (e.g. Kenyon 1966a39; 1970182); “… Unfortunately”, says Sdve-S&derbergh, “I think the architect Ricke is right in assuming that they are more probably temple foundations” (195160). In the work to which he refers, Ricke makes the point that the date of both these “fortresses” is so far quite unsettled, and that at Tell el-Yahudiyah the gentle outer slope of the “rampart” would actually favour attackers; in addition, this site shows no trace of either a defensive wall or a moat, which makes it very hard to believe that the structure unearthed had any defensive purpose (cf. ibidn.5).

Interestingly, it was through the discoveries at Tell el-Yahudiyah that the rampart defences first came to be linked with the Hyksos. It was Petrie who first examined the site closely, and he declared it to be the remains of the Hyksos capital Avaris (Petrie 19069-10; cf. North 1967a87), thus linking both the rampart-style of defence system (as he believed it to be) and the style of pottery which he unearthed at the site (and which he termed Tell el-Yahudiyah ware) with the Hyksos. Later, when it was realised that Tell el-~Yahudiyah could not have been Avaris, the link between these two things and the Hyksos was inexcusably maintained. (The commonly assumed connection between the Hyksos and the so-called Tell el-Yahudiyah ware, which has also been found at many Palestinian sites, has been strongly criticised by both Soderbergh [195157 ] and Van Seters [196649-50] . More will be said of this erroneous link in the Excursus.)

Van Seters’ discussion of this style of fortification system leads him to assert:

“One criterion which should no longer be used in the dating of these defences is their correlation with the so-called invasion of the Hyksos from the north, or the establishment of a Hyksos empire in Syria and Palestine. Such historical speculation has seriously prejudiced the archaeological evidence. Furthermore, there is no reason, from archaeological data, to suppose that the similar development in fortifications in Syria preceded those in Palestine or that this style of fortification was originally derived from regions even further north” (196632). “There is no reason whatever to postulate, for the so-called Hyksos defences, any immigration either of a new people or of a new warrior aristocracy in the latter part of the MBII period” (ibid37).

To sum up the above materialthere is no evidence for linking the Hyksos rule in Egypt with a Hurrian migration into Syria and Palestine; there is no evidence for any such migration having taken place until long after the time of the Hyksos; there is no evidence for linking the rampart fortifications with either the Hurrians or the Hyksos. In short, Kenyon’s view that the rampart fortifications constitute “the material evidence of the Hyksas period in Palestine” (1966a39) is without foundation.

Some of the facts reported by Kenyon herself actually seem to militate against any connection between the rampart defences and the Hyksos. She says:

“As far as Palestine is concerned, the introduction of the new type of defence meant no break in culture. From the first beginnings of the Middle Bronze Age down to its end, and long past it, all the material evidence, pottery, weapons, ornaments, buildings, building methods, is emphatic that there is no break in culture and basic population” (1966a39).

With specific reference to Jericho we have it stated “The Jericho evidence is emphatic that there is no cultural break” – i.e. at the time when the new fortification system was introduced there (1967269). Furthermore”There is no uniformity in the culture of the towns so defended” (1966a39). This would all seem to imply that the rampart defences should not be associated with any particular culture or incoming group of people, Hyksos or otherwise. However, Kenyon takes the above facts as “evidence of how foreign ruling aristocracies could impose themselves without altering the existing culture…” (1967269). This is clearly begging the question, as is the following, written more recently”From the material remains one would never deduce the setting up of a new ruling class, with its alien Hurrian elements, if it were not for the appearance of the new type of fortification” (1970193).

Certain of Kenyon’s recent works do contain indications that She may have begun to doubt the correctness of her own previous view concerning the destruction of MBA Jericho. One work, written ten years after her statement that the attack on the MBA city “can be identified with very little doubt as the work of the Egyptians” (1957229), contains this statement”The destruction might be caused either by Egyptian retaliatory forays against her Asiatic enemies or by the groups dispersed from Egypt” (1967272).

The third edition of her book Archaeology in the Holy Land still puts forward the view that the Egyptians destroyed the MBA cities, including Jericho (1970195-7), but in a slightly more recent work Kenyon appears to favour her previously offered alternative, for, writing of the numerous destructions at the end of the MBA, she says it is “likely that they were due to attacks by the groups of Asiatics displaced from Egypt at this stage” (19713) – by which she presumably means the Hyksos. The fact that Kenyon avoids using the term “Hyksos” here (and in 1967:272) obscures an important pointnamely that this suggestion is incompatible with the view, put forward by Kenyon in several works, that Jericho and the other fortified cities of the MBA were Hyksos fortresses. Those cities would obviously not have been destroyed by the Hyksos if they were occupied by the Hyksos. Yet to the best of my knowledge Kenyon has nowhere retracted her picture of a Palestine ruled by Hyksos overlords from these same cities.

But even when we do dispense with such a picture, as I believe we must, it is still difficult to believe that expelled Hyksos groups were responsible for the end of MBA Jericho. There is no evidence that such groups left Egypt and travelled to that area, and it is difficult to imagine why they should have destroyed Jericho (to say nothing of all the other MBA cities which fell at the same time) even if they had.

Kenyon’s belief that “a great number of the Asiatic Hyksos” poured into Palestine after the capture of Avaris by Egyptian troops, seems to be based on the testimony of Manetho, whom she cites in this connection (19713). But Manetho can hardly be considered a reliable source on the expulsion of the Hyksos, since his account of this event, preserved for us by Josephus, confuses it with the Exodus of the Israelites, and appears to confuse Sharuhen with Jerusalem (Josephus, Against Apion I, 73-90, 227-250).

I believe, however, that Kenyon’s expression “groups of Asiatics displaced from Egypt” does accurately describe those responsible for the destruction of the MBA cities – but I believe those Asiatics were the Hebrew tribes of the Conquest narratives, not hypothetical bands of marauding Hyksos, and that the time of the destructions was at least a century later than that suggested by Kenyon.

We may conclude by noting some cautionary remarks made by Van Seters “The use of the term ‘Hyksos’ to designate a style or type has created great confusion in the study of the archaeology of the period [MBA I] (1963). Such misuse of the term “begs the whole question of an open minded consideration of the archaeological evidence” (ibid). He notes that “Almost every instance of dating these [MBA I] fortifications has been by means of a correlation with a supposed Hyksos invasion”, and remarks”Such historical speculation has “seriously prejudiced the archaeological evidence” (ibid32 with no.8).

Yet, sadly, Van Seters himself illogically suggests that the fall of the fortress-cities “can best be understood as the activity of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs and the date for the end of Middle Bronze would be about 1550 B.C.” (ibid9). The suggestion is illogical because a view which denies any connection between the Hyksos and the fortified cities of the MBA provides no reason why those cities should have been the objects of Egyptian campaigns in the 16th century BC.

Returning to the specific problem of Jericho, our conclusions may be summarised thus there is no evidence at all that Jericho was occupied, fortified, or used in any way by the Hyksos; if Jericho was not a Hyksos stronghold, there is no reason why it should have been a target for the Egyptian army; there is also no reason why Hyksos groups expelled from Egypt should have attacked and destroyed Jericho. In short, there is no reason to link the fall of MBA Jericho with the political situation in Egypt and Palestine in the 16th century BC. The political situation in the 16th century BC provides no explanation for the violent end of MBA Jericho, and hence it does not require that the end of MBA Jericho be dated in that century.

If the end of MBA Jericho could be placed in the following century, the Israelite attack on the city recorded in the biblical narrative would provide an excellent explanation for that city’s sudden downfall, as we have seen. However, Kenyon sometimes refers to a further reason for placing its destruction in the 16th century BC, and to that we now turn.

3.3 The argument from pottery

Garstang believed that Jericho had been reoccupied almost immediately following the destruction supposedly wrought by the Egyptians. At the time of his excavations the pottery finds seemed to warrant this conclusion. (Garstang classified the restored city as a continuation of the MBA one. He placed the change to LBA in the middle of the 15th century, there being, he thought, a slight change in culture at that point, but no break in occupation. See Garstang 1940113-14).

Kenyon’s revision of Garstang’s dates for the LBA city involves a period of abandonment of 150 years or more between the destruction of the MBA city and the beginnings of LBA settlement. Kenyon insists that this period of abandonment is necessary because of the evidence of the pottery:

“When the [Garstang’s] excavations were in progress, the true transitional pottery from MB to LB, and that of LB I, was in fact scarcely known in Palestine, and well-authenticated examples have only been provided by the magnificently full publication of the material from Megiddo and Tell Duweir. It is now quite clear that this material … is completely lacking at Jericho both in the city and in the tombs” (1951115). “It must be strongly emphasized that the stratification of the town site shows a period of abandonment, and that the complete absence of pottery of the second half of the sixteenth century and of the fifteenth century B.C. makes it clear that the site was abandoned during this period (1967271-2).

I do not wish to dispute Kenyon’s assertion that there was a period of abandonment at Jericho. I wish to question, however, the date when she says this period began, which is, of course, the date at which the MBA city was destroyed.

The pottery which is completely absent from Jericho is the bichrome pottery sometimes described as transitional between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (Kenyon 1970198-200; Epstein 1966188). This pottery is commonly viewed as having spread to various sites in Palestine from two main centres, Megiddo in the north and Tell el-Ajjul in the south. At Megiddo, bichrome ware is confined chiefly to Stratum IX, to which Epstein has assigned dates of c. 1575-1480 BC (Epstein 1966:171-3). Its use is supposed to have spread southwards, having reached Ajjul shortly after its first use at Megiddo (ibid).

The view expressed by both Kenyon and Epstein concerning the origin and spread of bichrome ware, and the period for which it was in use, will be examined in detail in the following chapter, where it will be shown to be erroneous. It will also emerge that while Kenyon sometimes appears to use her date for the appearance of bichrome ware to deduce the date for the destruction of the MBA cities, the former is actually dependent on the latter, and not vice versa.

Here I wish simply to show that even within the framework offered by Kenyon and Epstein, bichrome ware cannot be used to date the fall of MBA Jericho.

There is no evidence that bichrome ware spread from Megiddo in a south-easterly direction any further than Taanach, a distance of less than ten miles; and from Ajjul it spread eastwards only as far as the Judaean foothills. In other words, from neither of its main centres did bichrome ware spread as far as Jericho. Indeed, its use seems to have been quite limited.

It does not seem to have spread appreciably into the highland regions of central Palestine, let alone as far as the Jordan Valley. (The only highland site which has yielded bichrome sherds to date is Beitin.) I would suggest in fact that its use barely extended beyond a 25-mile wide strip of the Syria-Palestine littoral. The plausibility of this suggestion is underlined by the recent discovery that bichrome ware was not manufactured in Palestine itself, as was previously supposed by Kenyon, Epstein and others, but was imported into Palestine from Cyprus (cf.Artzy, Asaro and Perlman 1973446-461). In other words, its spread was from the coast eastwards, not from Syria southwards as has commonly been supposed.

It is therefore reasonable to question whether the failure of bichrome ware (and other types of Cypriote pottery /6/) to appear at Jericho is of any significance at all for the chronology of the site. If its use never extended appreciably beyond the coastal plain, then its non-appearance at Jericho can obviously not be taken to imply abandonment of the city.

Kenyon herself says that Jericho’s geographical position may have resulted in cultural isolation. Lying east of the mountain range of central Palestine, it was “away from contacts with richer areas provided by the coastal route” (1967271). “…In comparison with places like Tell Ajjul, Megiddo and Beisan, in touch with the great trade route between Egypt and Syria, Jericho at this period [MBA] may have been something of a backwater” (1957253; also 1966a21). In view of these statements it is not unreasonable to ask why bichrome ware and other contemporary types of Cypriote pottery should be expected at Jericho at all.

It is very significant that “no bichrome ware is known to date” at Beth-shan (Epstein 1966118). Beth-shan is situated Similarly to Jericho, in the Jordan Valley to the west of the river, but it lies much closer to Megiddo than Jericho does to either Megiddo or ‘Ajjul. And here we have positive evidence that there was no period of abandonment. Epstein writes”…Evidence that it was not abandoned at this period is provided by an unpublished chamber tomb, T42, which contained the funerary offerings from many burials placed in it over a long period of time and dating to both before and after the floruit of bichromeware” (ibid).

This evidence makes it quite clear that the period of abandonment at Jericho cannot be dated from the absence of transitional pottery there. It could perhaps be argued that the absence of this pottery does not necessarily indicate a lengthy period of abandonment at all; however, the degree of erosion suffered by the ruins of the destroyed MBA city does indicate such a period, and I do not wish to deny that there was one. But the absence of transitional pottery tells us nothing about when this period began.

In short, the ceramic material from Jericho does not require the conclusion that the MBA city came to an end in the 16th century BC.

3.4 A new working hypothesis

We have seen that both criteria used to date the destruction of the MBA city at Jericho are in fact highly questionable. There is no evidence which compels us to date the destruction before 1500 BC; it could equally well have occurred some decades after that date. I submit,-therefore, that MBA Jericho actually came to an end in the second half of the 15th century BC, and that its aah were the Israelites as recorded in Jos 6.

If we date the Exodus to c. 1470 BC, and allow a full forty years for the wilderness period, then we should date the Israelite attack on Jericho to c. 1430 BC. We must remember, however, that our date of c. 1470 BC for the Exodus is somewhat provisional. Therefore we will not attempt to give a precise date to the fall of Jericho, but we may reasonably suggest a date somewhere within a decade of 1430 BC.

If the end of the MBA city is brought down to this time, what is to be made of the archaeological material from later periods, and how does that material correspond with information provided by the biblical traditions?

According to the biblical tradition, when the Canaanite city was sacked and razed, Joshua laid a curse on the site, and the city was not rebuilt again until the reign of Ahab, in the 9th century BC, i.e. the Iron Age (cf. Jos 626 and I Kgs 16:34).

Some remains, though not many, of an Iron Age occupation at Jericho have been found (cf. Kenyon 1957263-4). But what of finds from the intervening period?

The biblical traditions do imply that temporary settlements were occasionally made at Jericho in the intervening period. Thus in Jdg 313, we read that Eglon, King of Moab, along with groups of Ammonites and Amalekites, took possession of Jericho (see Deut 343 for another example of the use of the title “city of palms” to designate Jericho). And in II Sam 105 it appears that some sort of occupation, though perhaps only a military station, existed at Jericho in the time of David.

The establishment of some sort of temporary settlement at Jericho by Eglon of Moab, which would fall somewhere in the LBA, would account adequately for all the LBA finds on the tell – the scarabs, the pottery from the tombs and the mound, and the scanty building remains. It seems much more reasonable to suggest that these are the remains of a temporary, unwalled settlement on the site than to suggest that they are all that is left of a fortified LBA city.

It is in fact only because Kenyon believes the events of Jos 6 “must” belong in the LBA “by any dating” (1957262) that she posits the existence of a proper town in this period at all. The archaeological finds alone certainly do not require such a suggestion. The LBA archaeological evidence (or rather the lack of it) is accounted for much better if it is suggested that there never was a city as such at Jericho in the LBA, only sporadic habitation. This would explain the paucity of house remains, the complete lack of any trace of a city wall, and also the fact that no proper LBA tombs are attested, only the re-use of certain MBA tombs by the later settlers (cf. Kenyon 1957260-61; 197120-21). It would also account for the absence of references to Jericho in the Amarna correspondence.

Concerning the settlement which seems to have existed in David’s time, we may note that according to Albright and Wright, the so-called “hilani” building at Jericho may date to the 10th century BC, though a date in the 9th century (Ahab’s time) is also possible (cf. Wright 1962a79).

It is felt that the scheme proposed here offers a more consistent treatment of the archaeological evidence than hitherto, as well as providing a complete explanation for the origin of the Jericho tradition.

In the following pages we will examine evidence from various other cities mentioned in the Conquest narratives, to see whether this dating of the end of the MBA can operate satisfactorily at those sites also. At these other sites a new problem arises, however, for, unlike Jericho, they do not all lie beyond the regions where bichrome pottery came into use. Since the presence or absence of bichrome pottery has often been used as a criterion for dating the fall of the MBA cities, the whole question of when this pottery came into use and for how long it remained in vogue must be examined in some detail. This will be our next undertaking.