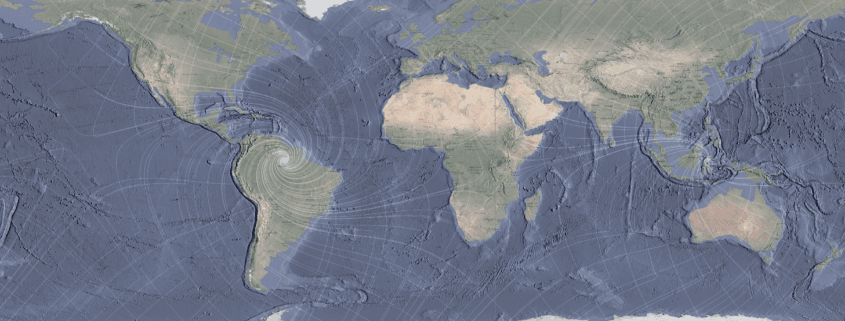

“[An excerpt from] Kenneth J. Hsü’s firsthand account of one of the most fascinating deep-sea drilling cruises ever launched. This voyage, Leg 13 of the Glomar Challenger, was undertaken in 1970 and led to a spectacular geological headline: the hypothesis that about five and a half million years ago the Mediterranean Sea was a desert.”

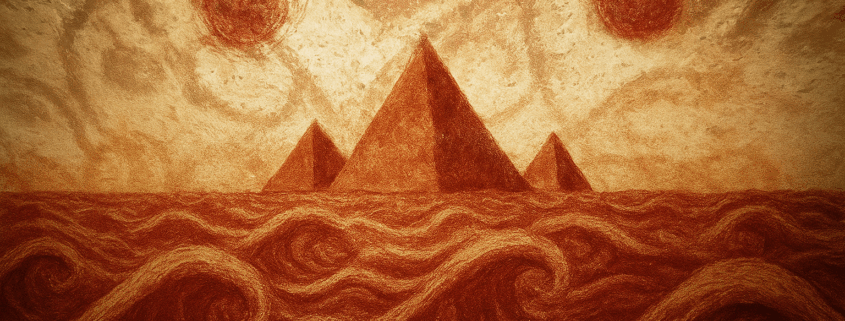

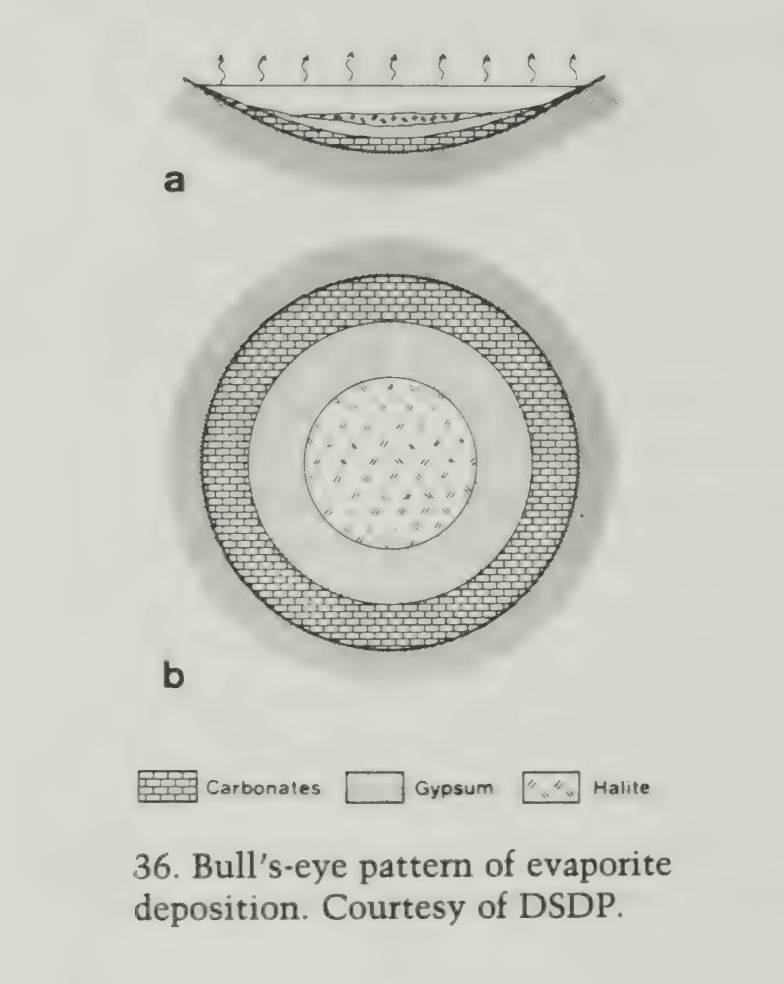

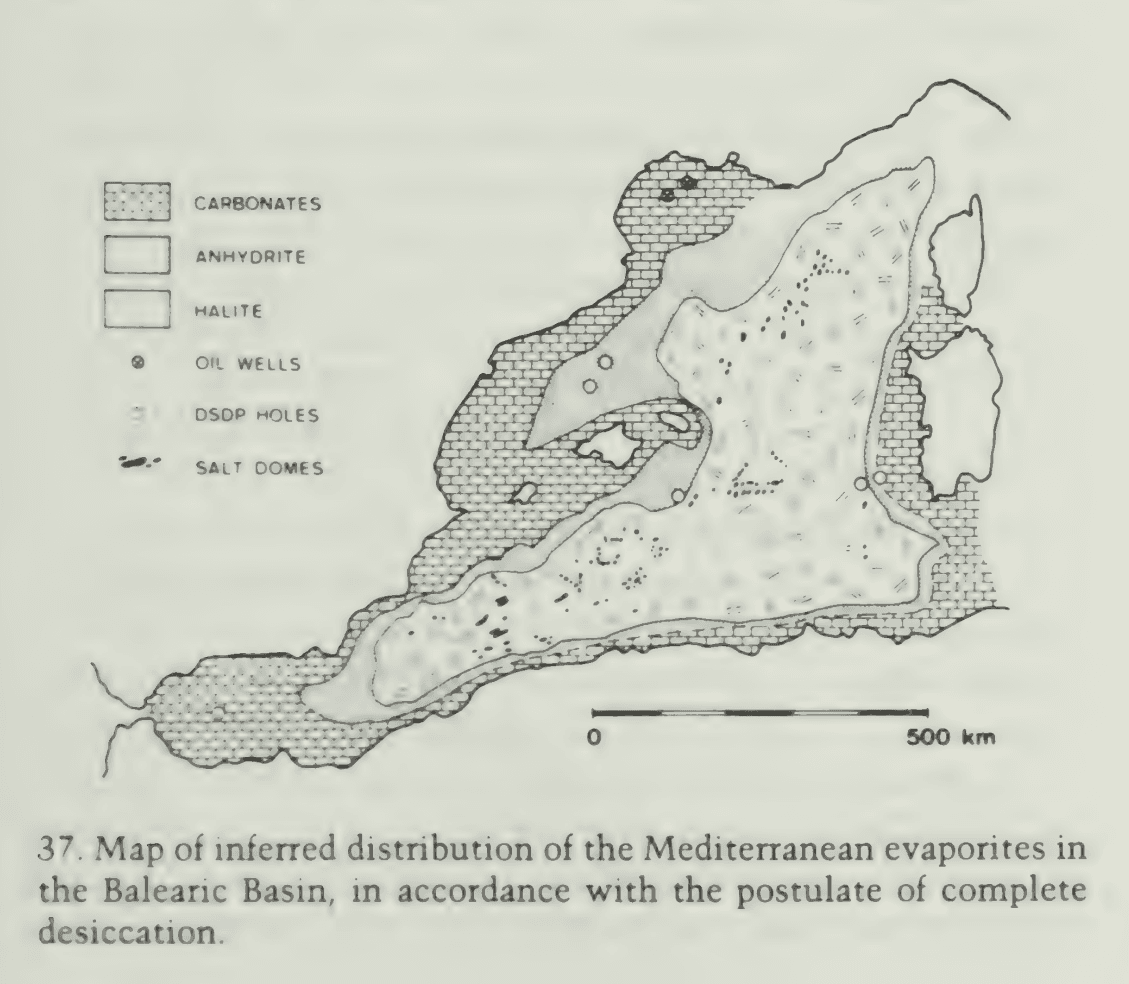

“Bull’s-eye” was an expression used by Bob Schmalz to describe the distribution of playa evaporites. He recognized two different patterns for two different modes of evaporite deposition. If a suite of evaporites had precipitated out of a deep brine pool maintaining a restricted communication with the open ocean, the evaporite distribution should appear on map in a teardrop pattern; the most soluble salts, and the last salts to settle out of a bittern, should appear at the end farthest away from the pathway to the open ocean. If, on the other hand, evaporites were residues paving the floor of what had been a completely isolated basin, the first salt to precipitate on the periphery would be carbonate — a limestone or dolomite. As the water level dropped and the brines became more concentrated, a ring of sulfates would settle out. Finally in the center or deepest depressions of a salt pan, we should find the bull’s-eye, where halite and other more soluble salts would have been precipitated (fig. 36).

Our drilling results so far permitted us to continue contemplating a bull’s-eye in the Mediterranean. We had found sulfate deposition on basin margins slightly above the abyssal plains (fig. 37). And our seismic records indicated that there must be rock salt under the central abyssal plains, for we were certain by now that the array of pillar-like structures could not be anything but salt domes. All we needed to prove our interpretation was to obtain a salt sample. The trouble was that we could not drill on a salt dome because of the probability of encountering an oil reservoir and the ensuing danger of pollution. Where we could drill we could not expect to get through to the salt. To discourage us, Anderson swore that we would never take a salt core with our primitive equipment, even if we drilled straight into a salt bed. He was sure the salt would be long gone before we could raise the core barrel, being dissolved by the seawater pumped down the hole as circulating fluid. Ryan and I had felt very frustrated throughout the last few weeks. We were almost sure we had a bull’s-eye there — one more proof that the Mediterranean had dried up. We wanted very much to bring up a piece of rock salt, but we could not permit ourselves enough optimism to plan for such an operation.

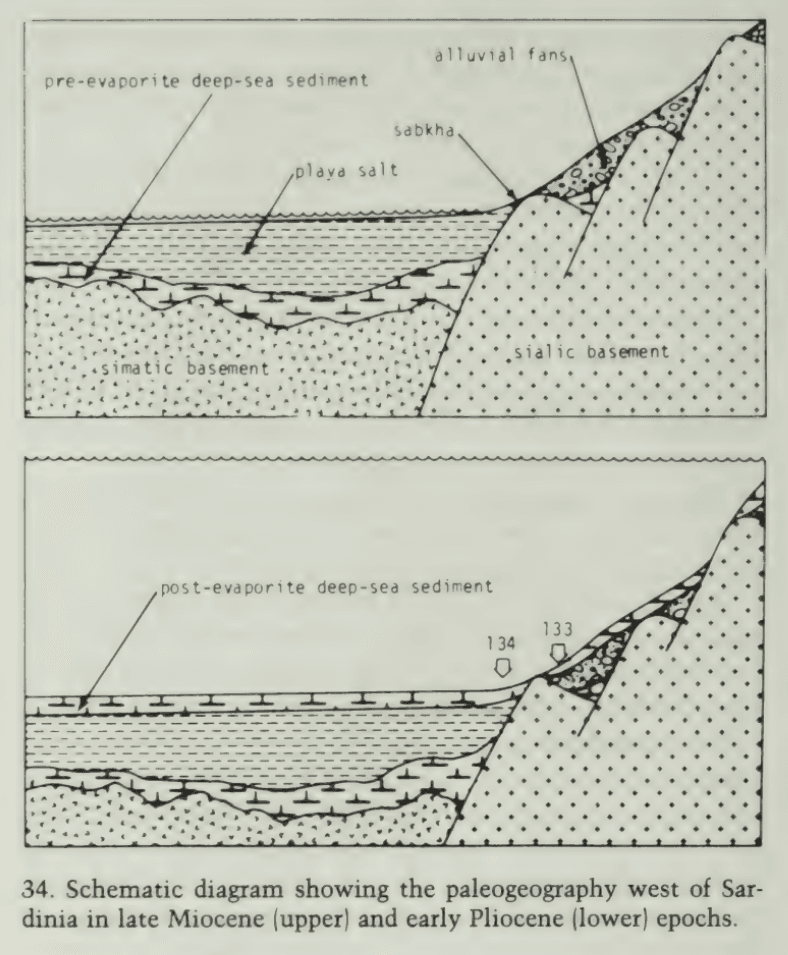

In the late morning of the twenty-ninth Anderson left us alone in our cabin to choose our next, and last, drilling location. Our drilling results at Site 133 had indicated that the “basement high” was not a volcano as we had thought, but a “basement ridge.” The seaward side of this ridge was buried under a thin wedge of abyssal plain sediments (fig. 34]. Time was then getting short, and I was still obsessed with getting down to basement. So I proposed that our next drill site be located near the top of the ridge where the sedimentary cover was thin. Ryan made a counterproposal that irritated me to no end; he wanted to drill farther seaward at the foot of the buried ridge where the basement was covered by at least several hundred meters of sediments.

“We could not possibly get to the basement under the thick abyssal plain deposits there.” I was exasperated. “I know; but we have a few days of ship-time left. We don’t need to panic. We can reach basement on top of the ridge anytime we want to. But we still have time to drill a hole in the basin before making an offset on the ridge. I want very much to find another record of the Pliocene deluge here in the Balearic. We missed it when we drilled Hole 124.”

“We don’t have time for that. If we want to make sure that we hit Miocene-Pliocene contact, we have to do continuous coring. We simply do not have that kind of time!”

“We don’t have time for that. If we want to make sure that we hit Miocene-Pliocene contact, we have to do continuous coring. We simply do not have that kind of time!”

“It’s worth a try, Ken.” Ryan was now trying all kinds of persuasion to win his case: “The drilling crew is nervous and jittery now, having run into so much trouble lately. If we drill on the buried ridge where the sediment cover is thin, we might reach basement. But the bottom-hole assembly could get stuck in the hard rock and be twisted off before the hole could be stabilized. Then everybody would be upset. We have to do something safe now to soothe their nerves and boost their morale. If we spud our next hole in the basin, we won’t be getting into any trouble. They could easily slip through several hundred meters of section and they would have a sense of achievement. Meanwhile, the drill string can be stabilized and we won’t get stuck. We could then try the ridge top offset. We’ll have plenty of time to do that before we have to leave for Lisbon.”

“Okay, you win. We’ll try the basin hole,” I gave in unwillingly. “But we absolutely have no time for continuous coring.”

“We don’t need to anyway until we get near the M-reflector a couple of hundred meters down. We can wait until our seismic record tells us that we are getting near.”

“But you know now how lousy your seismic is. We are never sure where we are. If we don’t miss the top of the reflector by a hundred meters, we’ll miss it by fifty at least. And even that will mean six barrels of continuous coring for nothing; we’ll be wasting our time.”

“No, we’ll make the contact in five hours. Anyway, there is no harm in giving it a try. You will have plenty of time for your basement hole.”

So another compromise was made. We went to the electronics lab and spread out our seismic charts. Pautot’s Charcot survey gave us an excellent record. We could identify the M-reflector. We could even recognize a seismic reflecting horizon, which signified a layer of rock salt. We noticed that this layer lay only a few hundred meters below the sea floor at Ryan’s proposed location, but neither of us ventured to mention it as a coring objective. We did not believe that we would be lucky enough to get down there before it was time for us to quit again. Or perhaps we did not want to alarm Anderson prematurely.

Anyway, a new location was picked, and its coordinates were communicated to the captain. I wrote a new prognosis announcing the site to our shipmates. They were upset that we had to move again, but they were too tired to protest. It was only a short ride, and we arrived at Site 134 at 1705 in the afternoon.

We had a very frustrating beginning at our new location. First we had difficulties again with Anderson. The disagreement was over a technical triviality, but his insistence on doing everything the extra-safe way cost us a couple hours of valuable ship-time. We had been very lucky so far and had lost no equipment, but we began to suspect that Anderson was more concerned about keeping a clean slate on that score than about scientific objectives. He, the drilling superintendent, and the toolpusher seemed to be fooling around here; and the crew did not get set to spud the well until after dark. Once we finally got started, we drilled through the soft stuff without any difficulty. But after we had drilled only 170 meters, the needle on the pressure gauge flicked, a sign that we had hit hard rock. This was about a hundred meters short of the M-layer, as Ryan had calculated it. He immediately decided to take the first core, thinking we might have misidentified the M-reflector.

Thus we started coring operations sooner than planned. All evening long people asked me when we expected the first core to be up. I kept saying: “Soon — in about two hours.” Late in the evening I quit guessing. The core came in after midnight, three or four hours later than we had expected, and all we had was a barrel full of water. By then Ryan had gone to sleep for a couple of hours; I asked the toolpusher to cut another core immediately below. Ryan relieved me at about two o’clock in the morning. When I went down to breakfast at six, Ryan told me that he had had a terribly frustrating night. Nothing seemed to work, and we had recovered practically nothing. He had such a backache now that he had to get some rest again. Backaches always seem to get worse when things go wrong.

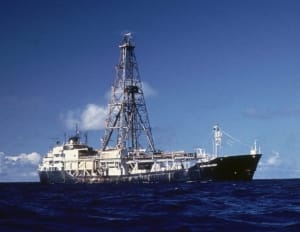

Glomar Challenger

So I took the logbook and went well-sitting. It was a beautiful morning. The sea was calm and the wind was still. Jim, the toolpusher, had promised for some time that he would take me up the elevator to the top of the drill tower. That morning I finally put a roll of film in my camera and took him up on his offer.

It was an open-air lift. One almost had the feeling that one was going up the Eiffel Tower. And the view from the top was glorious. Stacked neatly below at the bow were rows and rows of drill pipes. Looking astern into the sun, I saw the bridge and our living quarters. Some early risers were already on the deck enjoying the morning sun. On my way down I was given a demonstration of the esteem and affection that the roughnecks held for their chief scientists. I was to be lifted from the elevator of the derrick tower by a crane and lowered down to the rig floor. But the crew left me suspended in midair during the transfer. Furthermore, they threatened to train water hoses on me to give me an early morning shower. Jim, the old reliable, also joined in the fun. When I was finally let down, I had to scowl at him and reply, “Et tu, Brute!”

Soon we had our fifth core — and our first success. We actually found some mud in the barrel. From this, Cita told us that we were still in the Pliocene, quite a distance above the top of the evaporite series. All morning we had proceeded cautiously. We did not have enough time to core continuously. On the other hand, we did not dare move too fast lest we miss our contact. Things went along fine for awhile; we got some cores, but I kept revising the depth at which we expected to encounter the M-reflector. The drillers poked fun at me again, suggesting that I start a lottery.

Shortly after lunch, Ryan woke up and inquired about our progress. He was at least consoled that we were bringing in cores, even though his optimistic appraisal of meeting the M-reflector in five hours proved completely unrealistic. Almost twenty-four hours had gone by — precious hours had been reserved to investigate the basement below the evaporites, but we had not even reached the evaporites. Worse still, we began to encounter sand layers. Perhaps the reflectors on the seismic record were in fact not layers within the evaporite formation at all, but cemented sandstone in a Pliocene abyssal plain sequence. Ryan and I began to worry that we had completely misread our seismic record.

Since I was short on sleep, I should have left the wellsitting duties to Ryan, but I was too keyed up to go to bed. I had read all the old paperbacks on the shelves in the science lounge, so I went to the science office to read old cruise reports as an exercise in relaxation. I took out the two thick volumes prepared by Jerry Winterer and his crew when they went to the Marianas in the Pacific.

After a couple of hours I was ready for bed. But since it was just about time for another core to come up, I thought I might as well go to the rig floor to take a last look. Coming out of the science office, I bumped right into Ryan in the gangway. He had a shining icicle in his hand. “Taste it,” he exulted. “It’s salty. We hit rock salt!” It was a complete surprise for all of us.

Ryan led me to the core lab. The room was full of people — scientists, marine technicians, roughnecks, sailors, even the cook. All had come to admire the salt core. It was indeed partially dissolved by circulating seawater as Anderson had predicted, but we had hauled it up!

Since all of the scientists were in one room, perhaps for the first time during the cruise, we decided to have group pictures taken to commemorate this historic occasion. Someone woke up Orrin Russie, the photographer, and we all got set posing for publicity. The captain was called in. They also found Anderson. Just this moment Jim, the toolpusher, came in and asked me quietly:

“How much did we get?”

“Salt!” I said, still beside myself.

“No, I mean how many meters of cores did we get?” The toolpusher had to keep record of meters cored and recovered in his book.

“Oh, I don’t know. Put down 0.5 meter for your record, but it is worth more than a thousand meters of mud!”

This was the first time that rock salt had ever been recovered from the ocean floor, and we had hit the bull’s-eye in the Balearic 3,000 meters beneath the sea!

– The Mediterranean was a Desert – A Voyage of the Glomar Challenger, Kenneth Jinghwa Hsü (1983)