The extent to which the fear of recognition that we travel on an accident-prone vessel governs the thinking of modern science can be exemplified by a few instances.

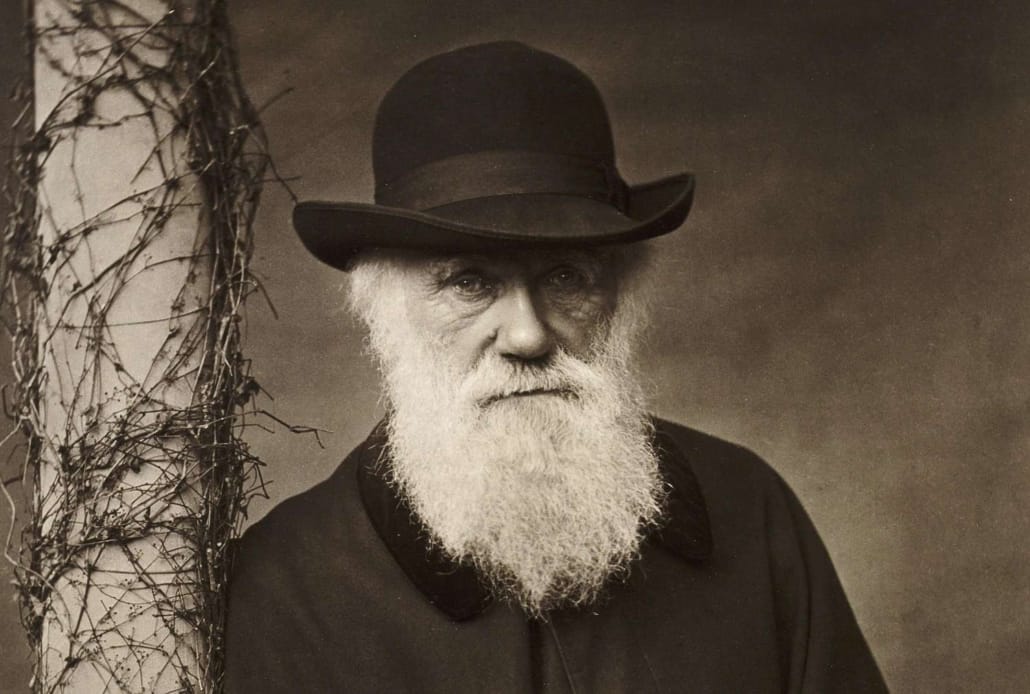

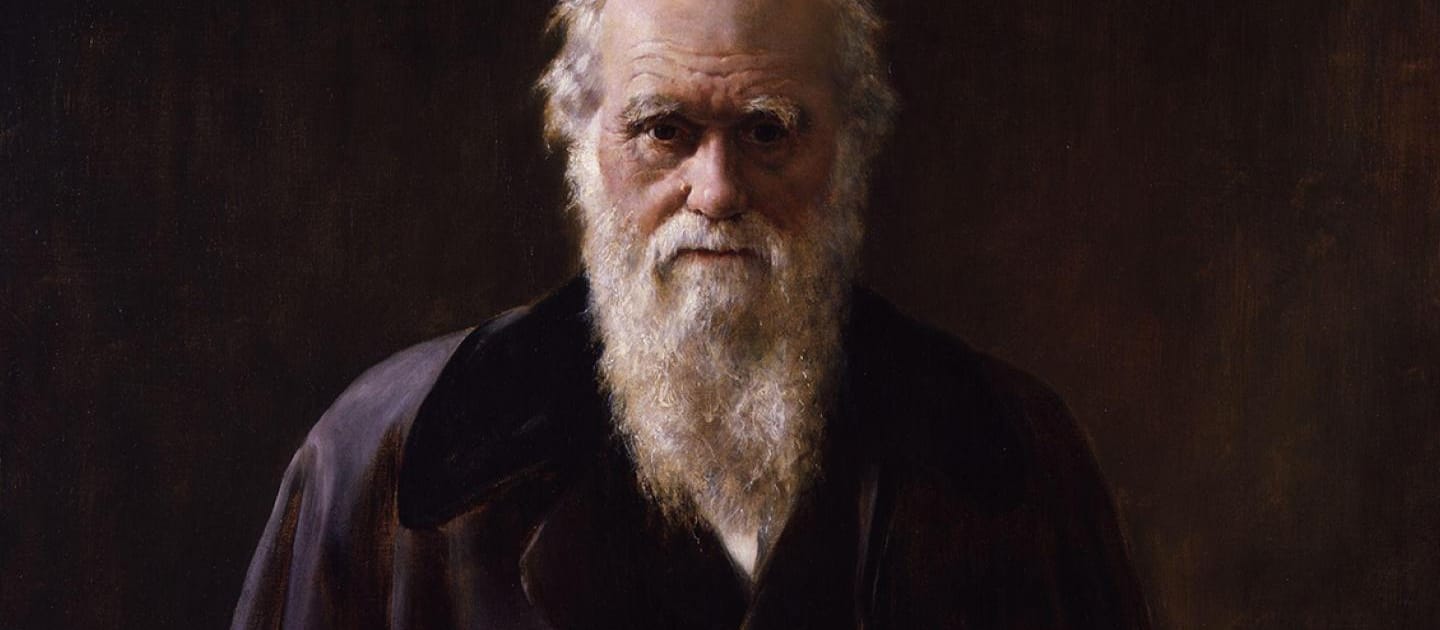

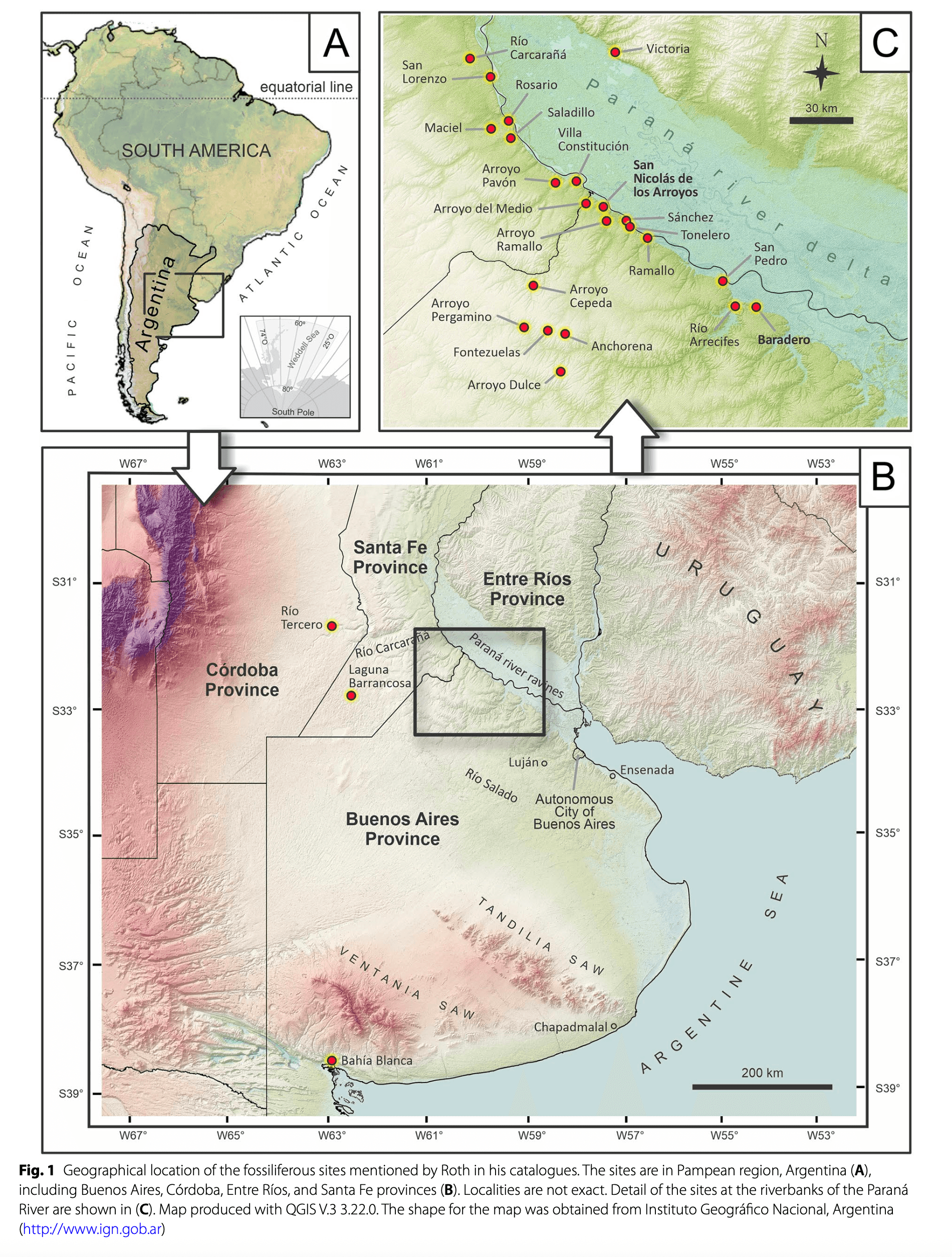

Charles Darwin, as a young naturalist, visited South America; it was in fact the scene of his by-far-longest stay in the course of the circumstantial voyage on the ship Beagle. He wrote in his Journal of his voyage (I have also quoted the passages in Earth in Upheaval): “It is impossible to reflect on the changed state of the American continent without the deepest astonishment. Formerly it must have swarmed with great monsters: now we find mere pigmies, compared with the antecedent, allied races.”

He continued: “The greater number, if not all, of these extinct quadrupeds lived at a late period, and were the contemporaries of most of the existing sea-shells. Since they lived, no very great change in the form of the land can have taken place. What, then, has exterminated so many species and whole genera? The mind at first is irresistibly hurried into the belief of some great catastrophe; but thus to destroy animals, both large and small, in Southern Patagonia, in Brazil, on the Cordillera of Peru, in North America up to Behring’s Straits, we must shake the entire framework of the globe.” (Italics added.)

He continued: “The greater number, if not all, of these extinct quadrupeds lived at a late period, and were the contemporaries of most of the existing sea-shells. Since they lived, no very great change in the form of the land can have taken place. What, then, has exterminated so many species and whole genera? The mind at first is irresistibly hurried into the belief of some great catastrophe; but thus to destroy animals, both large and small, in Southern Patagonia, in Brazil, on the Cordillera of Peru, in North America up to Behring’s Straits, we must shake the entire framework of the globe.” (Italics added.)

Darwin did not know the answer and he wrote: “It could hardly have been a change of temperature, which at about the same time destroyed the inhabitants of tropical, temperate, and arctic latitudes on both sides of the globe.” It was not man who acted as a destroyer; and were he to attack all large animals, would he also, Darwin asked, be the cause of extinction “of the many fossil mice and other small quadrupeds . . .”? Darwin concluded: “Certainly, no fact in the long history of the world is so startling as the wide and repeated extermination of its inhabitants.”25

Having seen what he did in South America, Darwin could not but embrace catastrophism. He did not come by his information through mere reading; he saw the very remains of catastrophe victims, not in museums, but in situ, in the pampas and on the slopes of the Andes. Such an experience is more compelling than literary information. Yet, two decades later Darwin propounded a non sequitur in ascribing all changes in the animal kingdom to a very slow evolution through competition, and by an extended dialectic he endeavored to demonstrate that the earth pursued a stable evolution on a stable course of uninterrupted circling, because the idea of a shaking of the entire globe was mentally beyond him. But he saw these animals, their bones splintered, heaped in the strangest assemblages—giant sloths and mastodons together with birds and mice. He had to forget these pictures of disaster in order to invent a theory of a peaceful earth unshaken in its entirety—an earth populated by species competing for livelihood, and benefiting from chance variations, all of them evolving from a few unicellular organisms, as though mere competition (“survival of the fittest”) could produce from the same animal ancestor a winged bird, a winding snake, a multilegged insect and man. With our present knowledge of the phenomena of transmutations of elements and biological mutations that take place in extreme conditions, thermal or radioactive, we no longer need subscribe to the idea that eons of competition for the means of existence caused wings to grow on land creatures and the entire population of land, air and water to evolve from a common ancestor. But whatever the cause of evolution—in his time Darwin could not know of the phenomenon of mutation—the phenomenon of destruction of a multitude of genera and species was known to him, and he could not pass over it in silence in the Origin of Species. He wrote: “The extinction of species has been involved in the most gratuitous mystery. . . . No one can have marvelled more than I have done at the extinction of species.” But then he chose to find an explanation in “wide intervals of time between our consecutive [geological] formations; and in these intervals there may have been much slow extermination.”26

This explanation, assuming lacunae in the geological record, without which there would have been found evidence of gradual extinction of “unfit” species, does not help to explain the observed hecatombs of animals, not only of extinct species but in a melee with still-extant forms which also succumbed in the same paroxysms of nature. These remains were obviously heaped together in single actions of nature with no geological hiatus intervening. The heaps of perished animals in South America and all over the world were widely known in Darwin’s days: Alfred Russel Wallace, who simultaneously with Darwin announced the theory of natural selection, in puzzlement drew the attention of the scientific world to the Siwalik hills, at the foot of the Himalayas, their several hundred miles of length practically packed with bones of animals.

One may frame hypotheses for what one does not see, like the hypothesis of geological gaps, the foundation of the entire Origin of Species. But for what one does see, the evidence of great cataclysms, it is no explanation to assume a defective geological record.

The Christian Church maintains that animals have no souls and that an unbridgeable gulf exists between the kingdoms of man and animal. When Darwin destroyed the sense of absolute separateness of man and animal, he undermined belief in the soul’s being separate from and surviving the body. Thus Darwin deflated man’s pride in his origin and uniqueness. But there was another aspect of Darwin’s theory, without which the opposition to his teaching would have been much more intense and prolonged. This was a feeling of security about the peaceful history of our planet, the abode of man—no catastrophic interruptions in all the eons of the past and none in the future. For that assurance, man was ready to part with the idea of his uniqueness and agree to be counted as one of the animal kingdom. This did not require his giving up his status as number one, free to exploit and even consume any of his animal brethren, regardless of their position on the ladder of evolution. He did not need to accord franchise to horses or primates: his own female folk were not yet granted voting rights. It was more like finding that the genealogical list one thought to be genuine was actually not so, and the assumed nobility was not based on the ancestors’ high ranking; there was no blue blood flowing in the veins of the primates. This loss occasioned the satirical question Bishop Samuel Wilberforce directed to Thomas Huxley during their famous encounter: “ . . . was it through your grandfather or your grandmother that you claim to have descended from a monkey?”

So man was offered an opportunity to barter his godlike origin for the security of his abode. Darwin knew the sacrifice (in intangibles) he asked and the guarantee of peace of mind he offered. Who cares for the past if the future is at stake? Darwin made it clear on the concluding page of the Origin of Species: “As all the living forms of life are the lineal descendants of those which lived long before the Cambrian epoch, we may feel certain that the ordinary succession by generation has never once been broken, and that no cataclysm has desolated the whole world. Hence we may look forward with some confidence to a secure future of great length.”

Darwin ended the Origin of Species with these words: “There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.”

The plot now being settled, the drama of everyone against everybody else could go on without any fear that the stage itself would collapse. For man at the top of the ladder it was like a license to devour or exploit the less developed—soul or no soul; for man, this battle of survival in the animal kingdom is usually no more than sport. In any case, what all this did was quickly to bestow a century-long enduring victory of Darwinism over man’s hidden apprehension as a descendant of survivors of catastrophes of unfathomable destructive power.

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection appeared in November of 1859 and was an immediate success: on the day of publication, the whole edition of 1,250 copies was sold out.

In books on the history of science, and more specifically in books on Darwin, one regularly reads of the bitter opposition the book provoked. This statement needs qualification. It is true that the great names in science of the time like Louis Agassiz, the ichthyologist, the botanist Asa Gray and others expressed upon reflection great reservations at Darwin’s views, yet they did so without disrespect and purely on scientific grounds. Agassiz pointed out that the skeletal remains of a number of ancient and extinct species of fish documented a better progression on the road of evolution and a better adaptation in the struggle for existence than do later species of fish, and thus the principle of the survival of the fittest had not been followed through. But the academic chorus in Darwin’s support was heard ever louder, and soon the spectacle in the intellectual circles was a rush to join the winning team. Thomas Huxley in England and Ernst Haeckel in Germany spearheaded the movement. Darwin kept himself in the background, but occasionally instigated his front fighters to demolish a scientific opponent, usually among the clerics, by circumventing scientific argument and attacking the critic personally, as was the case with a French savant, St. Georges Mivart, who offered solid arguments against the theory of evolution by natural selection. In his correspondence, Darwin referred to Lamarck, a predecessor in the teaching of evolution, by then long dead, as the author of “that wretched book.” Darwin also completely disregarded the work of the founders of the science of geology—Sir Roderick Murchison, William Buckland and Adam Sedgwick—of the early nineteenth century, who gave the names, still in use today, to almost all the geological periods—Cambrian, Permian, Ordovician, Cretaceous, etc. He also circumvented by silence the founder of mammalian paleontology and ichthyology, Georges Cuvier. These founders of earth science produced consistent data showing that catastrophic events on a global scale had repeatedly interrupted the flow of natural history. Darwin followed Charles Lyell, who was a lawyer by education and who argued the theory of uniformity not as a savant, but as a barrister; it was his book which Darwin read when he traveled on the H.M.S. Beagle and which, as he acknowledged, was his Bible.

Obviously there was a psychological need in Darwin to shut his eyes to contrary evidence, but also a similar need in both the academic and the lay society to get rid of the natural revolution by embracing natural evolution. One wonders at the avidity displayed by scientists in the acceptance of the Darwinian theory. None of the arguments that could have been used against him was utilized by his opponents. In his published diaries from his travels in South America, for example, a number of entries point to a cataclysmic interruption of the flow of the struggle for existence among life forms. There was not only the instance quoted earlier about the necessity to shake the frame of the entire world to account for the massive and sudden extinction of a multitude of animal species, but also the evidence of a rise of the coast of Chile by over a thousand feet in a period shorter than necessary for seashells to decay, and the repeated transgressions of the ocean all the way across Brazil to the foothills of the Andes. Yet with no new fieldwork by him between these observations and the Origin of Species, he protested in the latter against catastrophic changes of land and sea contours, and against any continental, much less global, upheavals. None of these contradictions between his diary observations and his views in his major work was raised by any of his opponents. It was not brought up against him that he had no academic position in a university, or that his only scholastic degree was that of a bachelor of theology, or that he omitted all footnotes to his sources, so that it was often impossible for a reader to check on the data; none of these shortcomings was ever mentioned by his critics. In addition to not heeding the solid finds of the still very young geological and paleontological sciences, Darwin, with all his entourage of acolytes, failed to learn of the work of his contemporary, Gregor Mendel, who evinced the basic laws of heredity and prepared the foundation for modern genetics.

Darwin’s was the spirit of the Victorian age—an evolutionary theory that was claimed to be a revolution, which it was not. Darwin became the supreme authority, the symbol of resolution of all questions, and a substitute for the Creator himself, who had to be suspected of being untrustworthy if the Mosaic books were inspired by him and the story of Creation now proved to be a fabrication.

The success of Darwin, the speedy acceptance of his theory by academia, and the penetration of his theory into all things spiritual and material of the last hundred years was due to his assurance that the frame of this globe had never been shaken.

Bibliography

25 Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, under date of January 9, 1834 (New York, London: Appleton & Co.), pp. 169–70.

26 Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, sixth edition (New York, London: Appleton & Co.), vol. II, pp. 95–96, 99.