Introduction

It is far easier to estimate coal reserves than oil and gas reserves. Like other sedimentary layers, coal beds extend over large areas, hence they can easily be mapped from surface exposures and their subsurface extent inferred. There has been much mining and exploration drilling for coal; in addition, many wells drilled for oil have penetrated coal-bearing formations. Because the coal-exploration geologist has a good idea of what kinds of sedimentary rock sections include coal and where to look for them, he is likely to be more concerned with thickness and quality of coal than with its presence or absence. For all of these geological reasons, accurate estimates of the world’s coal reserves are easier to make.

It is far easier to estimate coal reserves than oil and gas reserves. Like other sedimentary layers, coal beds extend over large areas, hence they can easily be mapped from surface exposures and their subsurface extent inferred. There has been much mining and exploration drilling for coal; in addition, many wells drilled for oil have penetrated coal-bearing formations. Because the coal-exploration geologist has a good idea of what kinds of sedimentary rock sections include coal and where to look for them, he is likely to be more concerned with thickness and quality of coal than with its presence or absence. For all of these geological reasons, accurate estimates of the world’s coal reserves are easier to make.

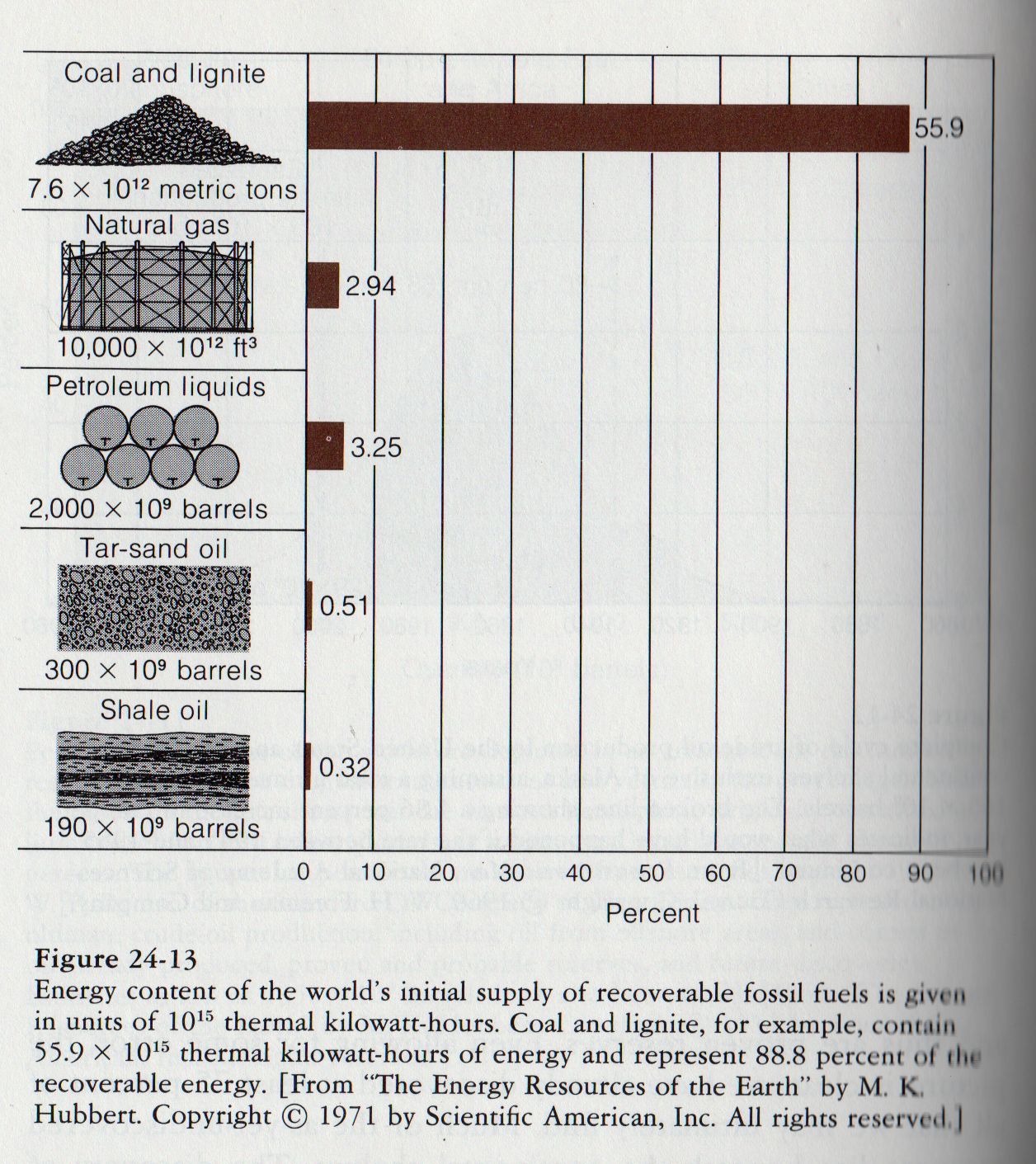

According to the best estimates made by the U.S. Geological Survey, about 7.64 trillion metric tons of coal remain unexploited. Thus we have so far used up only 1.7 percent. These figures include only coal deposits minable by present technology. Trillions of tons of additional coal exist, but the deposits are either so deep or in such thin beds that we cannot easily mine them by current methods. There are many new technologies that may possibly allow the recovery of such coal. Some experiments have already succeeded in chemically transforming the coal into gas while it is underground, without using mines or miners. Other ideas include underground combustion and conversion to steam or electrical energy. In any event, there is enough coal to last for a long time.

– Earth, Press & Siever (1974)

The Age of Oil

In On the Origins of Oil, D. Mendeleev (1877), challenges the prevailing biogenic theory of oil formation, which posits that oil originates from the decomposition of ancient organic matter. Mendeleev argues for a mineral origin, proposing that oil is produced through chemical reactions deep within the Earth, particularly involving water and carbonated metals like iron. Mendeleev disputes the evidence for oil originating from organic material, highlighting inconsistencies such as the absence of sufficient organic remnants in ancient geological layers. He proposes that oil forms when water penetrates Earth’s crust through cracks and reacts with carbonated metals, producing hydrocarbons under high pressure and temperature. The association of oil deposits with mountain ranges and straight-line geological features supports his hypothesis. Mendeleev draws parallels from meteorite compositions and the behavior of gases to support the idea of a deep, inorganic origin for oil.

In Science (24 October 1952), Paul Smith reported on the radiocarbon dating of oil deposits from the Gulf of Mexico:

“Ages of 11,800-14,600 ±1400 years were obtained for the hydrocarbons extracted from several sections of the Grande Isle core of Recent sediments. A composite carbonate sample from the entire core proved to be 12,300±1200 years old, and the non-extractable organic matter, which comprises a major portion of the original organic content, had an average age of 9,200±1000 years.“

Coal

Coal is found in layers that are ascribed to various ages mainly on the basis of fossils found in them. Brown coal is a compacted mass of plant remains. Lignite is made chiefly out of trees only partially converted into coal. Soft or bituminous coal is brittle and of bright luster and contains sulfur; its organic nature can sometimes be seen under a lens, and the plants that participated in its formation can be recognized by leaves in the shales on top of the coal bed. Anthracite or hard coal is metamorphosed bituminous coal. The plants that went into the formation of ancient beds include chiefly ferns and cycads; layers of later ages are composed of sassafras, laurel, tulip tree, magnolia, cinnamon, sequoia, poplar, willow, maple, birch, chestnut, alder, beech, elm, palm, fig tree, cypress, oak, rose, plum, almond, myrtle, acacia, and many other species.1

The origin of the coal beds is still far from being satisfactorily explained.2One theory would make peat bogs the place where, in a slow process measured by tens and hundreds of thousands of years, coal was born. It is said that the plants fall, but before they decompose in the air they are covered by the water of the swamps. A layer of sand is deposited over them, forming the soil for new plants, and thus the process repeats itself. In order that the layer of sand may be deposited, it is necessary that these marshy regions be covered by water in motion. Since almost regularly marine shells and fossils are found on top of coal beds, the sea must have covered the swamps at one time; then, for new land plants to grow there, the sea must have retreated. There are places where sixty, eighty, and a hundred and more successive beds of coal have formed; this theory would then require that as many times the sea trespassed – when the land slowly subsided – and as many times retreated. In other words, this theory assumes that the ground is pulsating and that the sea will return again sometime and cover the coal beds as it did a hundred times in the past.

“Fossils of marine clams, snails … are abundant in the shales just above each seam of coal. Later, with fluctuating sea level, the salt waters withdrew and another fresh-water marsh came into being, giving rise to another bed of coal above the earlier one. Again we are surprised, this time by the large number of such alternations of coal with marine sediments; these are now recognized as distinct cycles, each cycle representing a common sequence of events. … Ohio displays more than forty such cycles, and in Wales more than a hundred separate seams of coal have been discovered. Marvin Miller has given 400,000 years as the probable time represented by the average Ohio cycle.”3

This scheme demands not only that the sea should have covered the land one hundred times but also that after each retreat of the sea a fresh-water marsh should have appeared on the vacant ground in order to give the trees a place to grow and fall down and decay; and that the process of decay should have been checked before going too far, “for otherwise the vegetable matter would have disappeared completely and none would have been left in the form of coal.”4And then each time “not only was the areal extent of the marshes remarkable but the thickness of the coal required a surprising accumulation of vegetable matter.”

Many kinds of plants and trees that went into the formation of coal do not grow in swamps, and when they die they remain on dry ground and decompose. This fact suffices to render the peat-bog theory untenable.

Seams of coal are sometimes fifty or more feet thick. No forest could make such a layer of coal; it is estimated that it would take a twelve-foot layer of peat deposit to make a layer of coal one foot thick; and twelve feet of peat deposit would require plant remains a hundred and twenty feet high. How tall and thick must a forest be, then, in order to create a seam of coal not one foot thick but fifty?

The plant remains must be six thousand feet thick. In some places there must have been fifty to a hundred successive huge forests, one replacing the other, since so many seams of coal are formed. But it is further questionable whether the forests grew one on top of the other, because a coal bed, undivided on one side, sometimes splits on the other side into numerous beds, with layers of limestone or other formations between.

The consideration of the enormous mass of organic matter needed to form a coal seam brought about the birth of another theory of the origin of coal. Fallen trees were carried along by overflowing rivers, and coal was formed from them, not from the plants in situ.

This theory explains the enormous accumulation of dying plants in some localities; it may be able to show why, in many cases, a fossilized tree trunk is embedded in coal with its lower part uppermost, or standing on its head – which the peat-bog theory does not explain. But the drift theory cannot account for the fact that various kinds of marine life are mixed with the coal. Carbonaceous and bituminous shales are frequently packed with fossilized marine fish. Deep-sea crinoids and clear-water ocean corals often alternate with the coal beds.

Erratic boulders, too, are often encased in coal. It was supposed that these boulders were carried by chance on natural rafts of closely drifting logs and thus became embedded in the coal. Close rafts of drifting trunks are conceivable only after a great hurricane. However, marine fish would not enter deeply into inundating rivers to be entombed together with the boulders, and coral does not grow in muddy water.

Apparently the coal was not formed in the ways described. Forests burned, a hurricane uprooted them, and a tidal wave or succession of tidal waves coming from the sea fell upon the charred and splintered trees and swept them into great heaps, tossed by billows, and covered them with marine sand, pebbles and shells, and weeds and fishes; another tide deposited on top of the sand more carbonized logs, threw them in other heaps, and again covered them with marine sediment. The heated ground metamorphosed the charred wood into coal, and if the wood or the ground where it was buried was drenched in a bituminous outpouring, bituminous coal was formed. Wet leaves sometimes survived the forest fires and, swept into the same heaps of logs and sand, left their design on the coal. Thus it is that seams of coal are covered with marine sediment; for that reason also a seam may bifurcate and have marine deposits between its branches.

A support of this my view on the origin of coal I find in a recently published extensive work by Heribert Nilsson, professor emeritus of botany at Lund University.5Nilsson presents the results of an inquiry into the botanical and zoological composition of the brown coal (lignite) of Geiseltal in Germany, made by Johannes Weigelt of Halle and his group.6Many plants found in Geiseltal lignite are tropical, of species that do not grow even in the subtropics. A long list of tropical families, genera, and species, discerned in Geiseltal coal, was made known (E. Hoffmann; W. Beyn). Algae and fungi on the leaves preserved in the coal are found presently on plants in Java, Brazil, and Cameroons (Köck).

Besides the dominating tropical flora in Geiseltal, plants are represented there from almost every part of the globe. The associated insect fauna of Geiseltal coal is found “in present Africa, in East Asia, and in America in various regions, preserved in almost original purity” (Walther and Weigelt). The coal of Geiseltal is rated as belonging to the beginning of the Tertiary time.

As to the reptilian, avian, and mammalian fauna, the coal is a “veritable graveyard.” Apes, crocodiles, and marsupials (pouch animals) left their remains in this coal. An Indo-Australian bird, an American condor, tropical giant snakes, East Asian salamanders, left their remains there too (O. Kuhn). Some of the animals are of the steppe habitat, and others, like crocodiles, came from swamps.

Not only do the origin and the habitats of plants and animals offer a very paradoxical picture, but so also does their state of preservation. Chlorophyll is preserved in the leaves found in the brown coal (Weigelt and Noack). The leaves must have been rather quickly excluded from contact with air and light, or rapidly entombed: these were neither leaves falling off the plants in the fall nor leaves exposed to the action of light and atmosphere after being torn off by a storm. Entire strata of leaves from all parts of the world, counted by the billions, though torn to shreds but with their fine fibers (nervature) intact, in many cases still green, are found in the Geiseltal lignite.

It is not different with the animals. If exposed after death for any length of time to natural conditions, the structure of animal tissues loses its fineness; the muscles and the epidermis (skin) of the animals of the brown coal of Geiseltal were found to have retained their fine structure (Voigt). Also the colors of the insects are preserved in their original splendor. The very process of fossilization with silica invading the tissues must have occurred “fast blitzschnell” – almost instantaneously, in Nilsson’s opinion. While the membranes and the colors of the insects are preserved so well, it is difficult to find a complete insect: mostly only torn parts are found (Voigt).

Nilsson is convinced that the animals and plants found in Geiseltal coal were carried there by onrushing water from all parts of the world, but mainly from the coasts of the equatorial belt of the Pacific and Indian oceans – from Madagascar, Indonesia, Australia, and the west coast of the Americas. One thing is, however, evident: coal originated in cataclysmic circumstances.

– Earth in Upheaval, Velikovsky (1977)

Artificial Coal

In 1984 low-grade coals were produced in the laboratory from lignen (organic material) and clay (as catalyst) at 150°C in a period of only 2-8 months. These results call into question the claim that all coals take millions of years to form:

It was found that lignin heated with clay minerals at 150°C for 2-8 months in the absence of oxygen was readily transformed into an insoluble material resembling low rank coals. The H/C and O/C ratios were in the natural evolutionary range found for vitrinites with the samples from longer reaction times resembling the vitrinites of higher rank. The chemical and physical characterization of the artificial products indicated that their basic chemical structure closely resembles that of vitrinite macerals. Simple pyrolysis of only the lignin at 350-400°C yielded very different products with a substantialy lower H/C ratio and a higher O/C ratio than either transformed lignin with clay or vitrinites of any rank. Such products were found to correspond to fusinite in chemical structure. Macromolecules similar to alginites or type I kerogens were produced by heating fatty acids at 200°C with clays. The present study suggests that coal macerals could have been produced directly from the biological source material via catalytic thermal reactions.

Finger Mountain, Antarctica

Antarctica

By some estimates there are more than 0.5-1.3 trillion tons of coal to be found under the Antarctic ice-sheet, with seams more than 100m thick to be found in places. To produce 500 billion tons of coal deposits, an estimated 5–10 trillion tons of organic material would have been required, depending on the specific coalification conditions and the type of coal formed. Estimated total living biomass on Earth: 550 billion tons (dry mass). To match 5–10 trillion tons, it would take the equivalent of 9–18 Earths worth of biomass.

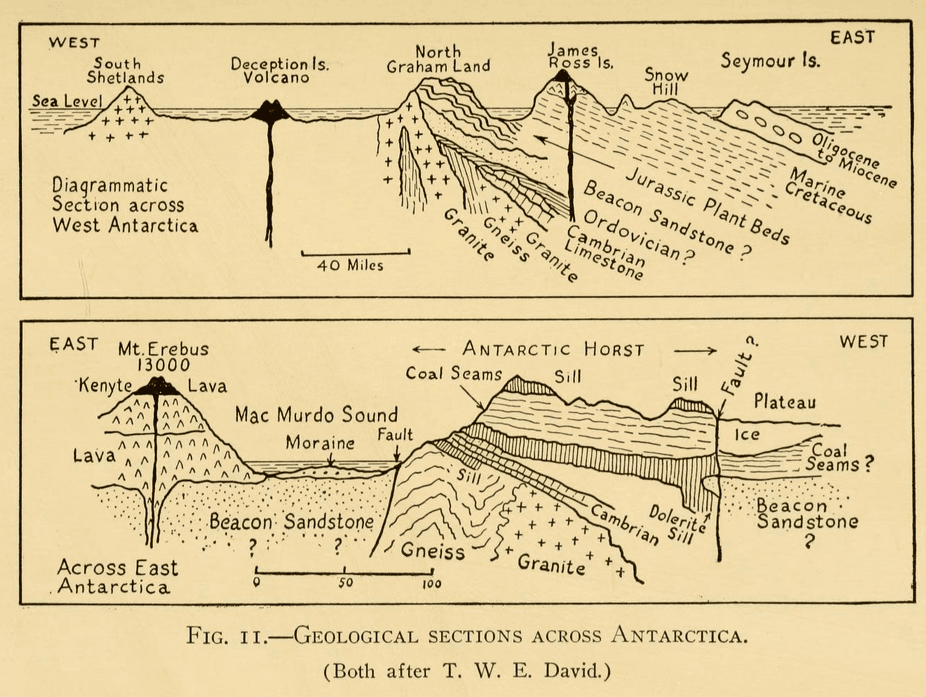

In Taylor’s Antarctic Adventure and Research (1930) we read:

Coal has been found in the Beardmore outcrops and also by my party near Mount Suess (latitude 77° S.). Dr. Gould has reported carbonaceous shales near the foot of Liv Glacier. The Mount Suess seams appear to occur with dark shales near the base of the sandstones. It is a hard bright coal with a large amount of ash. Probably it has been baked by the dolerite sills. The Beardmore coal, however, contains 14.5 per cent of volatile constituents and has not been baked to the same extent. Here Frank Wild recorded three hundred feet of coal measures containing seven seams of coal, from one foot up to seven feet in thickness. Fossil wood was obtained in the vicinity in 1908, which appears to belong to a gymnospermous plant, but much finer specimens of fossils were brought back by Dr. Wilson in 1912, and found near his body.

The fish remains collected by Frank Debenham and the writer on the moraine below Mount Suess in December, I9II, consist of dermal plates and scales. They are all isolated and scattered, showing that the fishes were disintegrated before burial, but the fragments are beautifully preserved, and in transparent sections their histological structure is perfectly observable.

Of greater importance still were the fossil specimens obtained by Scott and Wilson at the head of the Beardmore Glacier under Mount Buckley. Here Scott wrote on February 8th, 1912, “The moraine was obviously so interesting that when we got out of the wind I decided to camp and spend the rest of the day geologizing. We found ourselves under perpendicular walls of Beacon Sandstone, weathering rapidly and carrying coal seams. From the last Wilson with his sharp eyes has picked several pieces of coal with beautifully traced leaves in layers.’’ These were specimens of Glossopteris indica (see Figure 2) which, as Seward remarks, is one of the few genera which can be identified with confidence from fragmentary specimens. Their occurrence only three hundred miles from the Pole throws a light on the remarkable changes of climate which have occurred in the past history of the globe. Seward reconstructs the environment as follows: “The granites and gneisses from which the material of the Beacon Sandstone was derived, were in all probability exposed to the disintegrating action of wind-blown sand in a climate sufficiently mild to permit of the existence of Glossopteris and other plants. Fragments of leaves and twigs with larger logs of wood were carried by rivers or marine currents and buried in the barren sand that was being piled up on the floor of an Antarctic Sea, to be subsequently uplifted as vast sheets of sedimentary strata, which at a later stage were penetrated by the products of a widespread volcanic activity.”

This genus Glossopteris ranges from Upper Carboniferous to Rhaetic (Upper Triassic) period. Probably at Mount Buckley the beds are of Permo-Carboniferous age just as they occur in the coal measures of Australia. At the end of Carboniferous times, environments changed all over the world so that the old Lepidodendron flora (of Lower Carboniferous days) branched into two different types; one without much change in the Northern Provinces (Canada, Europe, China); and the other developed into the southern Glossopteris flora of India and the three southern continents. In most of these latter localities glacial deposits are commonly associated with the Glossopteris ferns.

Sir Edgeworth David has endeavored to estimate the extent and possible value of the coal reserves in Antarctica. The Beacon Sandstone is proved to cover twelve thousand square miles of available territory, but it is unlikely that coal measures are developed throughout. Our parties found no coal in the Ferrar-Taylor valleys. Possibly a great deal of coal exists under the Polar Ice Cap at a lower level than in the South Victoria Horst, where alone it has been observed so far. Probably it lies two or three thousand feet below the surface of the ice. If this hypothetical coal field were 700 miles long by 143 wide, and if the seams were only 12 feet thick, there are coal reserves here second only to those of the United States.

The mass of coal in the hypothetical field described by Taylor would be approximately 1.34 trillion tons.

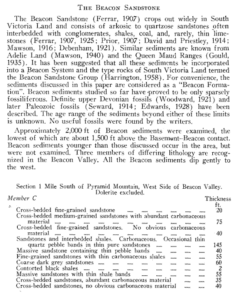

In Geological Investigations in South Victoria Land, Antarctica (1959) McKelvey and Webb make observation of 20ft of near-sterile sandstone atop 75ft of carbonaceous material observed in Beacon Valley:

Geological investigations in South Victoria Land, Antarctica, McKelvey & Webb (1959)

The Beacon Sandstone (Ferrar, 1907) crops out widely in South Victoria Land and consists of arkosic to quartzose sandstones, often interbedded with conglomerates, shales, coal, and, rarely, thin limestones (Ferrar, 1907, 1925; Prior, 1907; David and Priestley, 1914; Mawson, 1916; Debenham, 1921). Similar sediments are known from Adelie Land (Mawson, 1940) and the Queen Maud Ranges (Gould, 1935). It has been suggested that all these sediments be incorporated into a; Beacon System and the type rocks of South Victoria Land termed the Beacon Sandstone Group (Harrington. 1958). For convenience, the sediments discussed in this paper are considered as a “Beacon Formation”. Beacon sediments studied so far have proved to be only sparsely fossiliferous. Definite upper Devonian fossils (Woodward, 1921) and later Paleozoic fossils (Seward, 1914; Edwards, 1928) have been described. The age range of the sediments beyond either of these limits is unknown. No useful fossils were found by the writers.

In The Antarctic and its Geology (1978) Ford and Schmidt write:

“Low-grade deposits of coal are widespread, especially in the Trans-antarctic Mountains, but there has been no attempt at exploitation. Even if rich mineral deposits were to be found in Antarctica, except in a few areas the cost of removal from this remote and inhospitable land would be exorbitant.”

Cyclothems & Rhythmites

X0. Introduction. Even the casual observer of sedimentary rock formations recognizes their layered structures. Some sedimentary units are immensely thick, measuring many thousands of feet without discernable breaks in deposition. Millions of years may have been required for their accumulation. On the other hand, some strata consist of delicate laminae only a millimeter or two in thickness. Hundreds of thousands of these laminae may be counted in a single formation. Such laminae appear to be the sedimentary manifestation of some cyclic phenomenon; perhaps as long as the annual change in the character of the sediment carried into a lake, or as short as the deposit from an afternoon thunderstorm. Most strata and laminae suggest no anomalies, but some may record astronomical, geological, and meteorological processes and events we do not fully understand.

X0. Introduction. Even the casual observer of sedimentary rock formations recognizes their layered structures. Some sedimentary units are immensely thick, measuring many thousands of feet without discernable breaks in deposition. Millions of years may have been required for their accumulation. On the other hand, some strata consist of delicate laminae only a millimeter or two in thickness. Hundreds of thousands of these laminae may be counted in a single formation. Such laminae appear to be the sedimentary manifestation of some cyclic phenomenon; perhaps as long as the annual change in the character of the sediment carried into a lake, or as short as the deposit from an afternoon thunderstorm. Most strata and laminae suggest no anomalies, but some may record astronomical, geological, and meteorological processes and events we do not fully understand.

If a lamina or layer represents an annual deposit, it is termed a “varve”. However, it is sometimes difficult to prove that laminae are truly annual records. They may represent only a tidal cycle or perhaps something longer, say, a decade-long climate fluctuation. The word “rhythmite” is preferred here over “varve” because of this problem of identification.

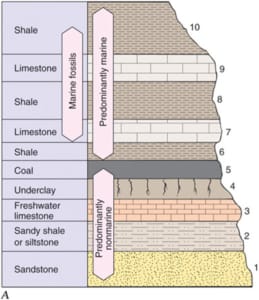

A “cyclothem” typically consists of a regular sequence of strata, such as clay/coal/shale/limestone/sandstone/etc., that keeps repeating, sequence upon sequence. The strata within a cycle then may be measured in inches of thickness, or many feet; they may be continuous for hundreds of miles. In general, cyclothems are more massive than rhythmites; but there is no “official” size criterion. The two terms are sometimes used interchangeably in this section.

Do rhythmites and cyclothems have different origins? The former are usually viewed as the consequence of short-term changes in the nature of the sediment being carried into a lake or estuary by water. In contrast, cyclothems are thought to be created by cyclic changes in the basin of deposition, such as wide-area subsidence or elevation. Climatic changes, too, may play a role in building cyclothems; but climate may control rhythmite formation also. Some extreme catastrophists even maintain that cyclothems are deposited quickly by massive floods or marine inundations.

In the rhythmites, the observed geological cycles (“cycles within cycles”) of thickness, chemical composition, organic content, grain coarseness, and other factors may seem to respond to tidal, sunspot, and earth-orbital factors. In fact, such strata parameters as the earth’s eccentricity, its tilt, and its distance from the sun are thought to modulate the layered structures.

From the viewpoint of the anomalist, the lack of consensus as to the origins of rhythmites and cyclothems provides much grist. But they may be deeper forces involved as delineated above under Description.

In the following sections, we will search out anomalies—sometimes in laborious detail—in the stratigraphic record, beginning with the Quaternary Period and working downward until we find that, even a billion years ago, cyclic phenomena modulated much sedimentation.

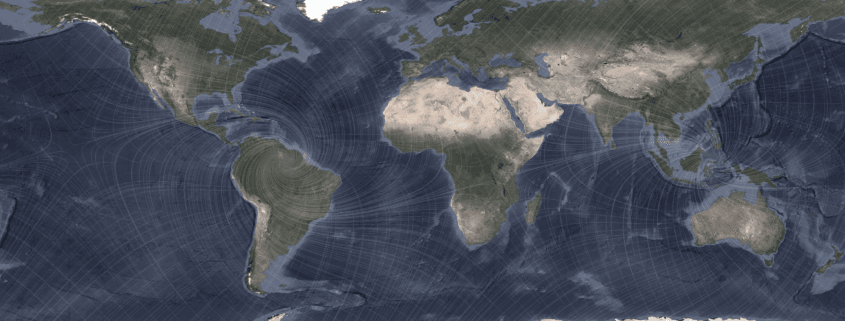

Worldwide occurrence of the Carboniferous cyclothems. Although the Carboniferous cyclothems are best-developed in the North American interior, they are also seen in the coal measures of South America, Europe, India, Australia, and Africa. This global synchronism has puzzled geologists for decades, as in this quotation from J.R. Beerbower.

‘The extremely wide geographic distribution of Carboniferous and early Permian cyclothems suggests that causal factors should be worldwide in extent. Some sort of catastrophic mechanism might be possible; Weller postulated a mechanism involving cyclic expansion and contraction of a subcrustral layer. It is easier, however, to visualize worldwide eustatic and/or climatic controls similar to those currently in action.’ (R24)

The last sentence is, of course, a statement of uniformitarianism. In this Catalog, all options are left open, even though the uniformitarian explanation–the “easier” explanation–seems reasonable here. (WRC)

The “fireclays” or “underclays” of the coal measures. Before exploring the full-fledged, many-element, coal-bearing cyclothems, we must mention the century-old debate about the nature of the so-called “fireclays” or “underclays” of the coal seams. These fireclays are highly refractory, often contain stigmaria (the supposed rootlets of ancient trees), and are generally thought to be the soil in which grew the plants that went into the formation of the coal directly above. The diversion here has significance because fireclays are integral elements of most Carboniferous cyclothems.

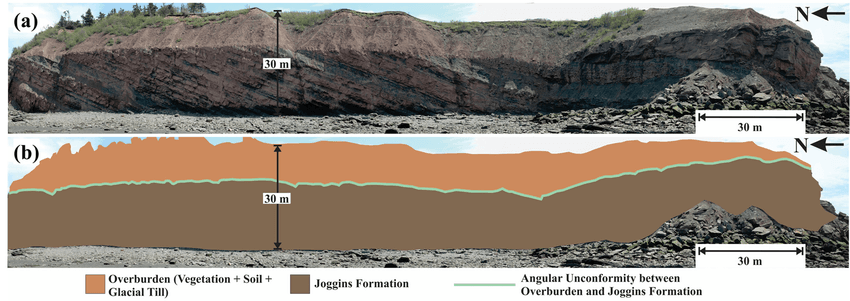

The first question to arise asks if coal seams and fireclays are always found together. The answer is: no. To illustrate, at the South Joggins coal measures, in Nova Scotia, one finds a section almost 3 miles thick, containing 76 coal seams and 90 underclays. It is obvious that fireclays can occur without coal. (R1) Further, coal itself, on rare occasions, does rest directly upon sandstone, without underclays at all. (R3)

South Joggins Cyclothems

To these facts, we must add that both underclays and coal seams reach great thicknesses. Underclays in England may exceed 30 feet in thickness; whereas one Australian coal seam is some 800 feet thick. (R3 and ESP3-37, respectively) It is hard to conceive of in-situ origins for such thick formations. C.F. Hopkins considered the fireclays to be transported deposits. (R3)

A final question involves the underclays of present-day peat beds. These underclays usually contain marine shells and fossils. The underclays of the coal measures, on the other hand, do not. Since the modern mainstream view of coal formation envisions an in-situ origin, with peat bogs often cited as modern coal formations in the making, the marine fossils in modern underclays present a contradiction. (R1) In fact, the evidence of the fireclays led at least one scientist, G.W. Tilliman, to claim that the firelay-coal couplets were actually varves! (R4)

We can see from this short treatment of fireclays the sorts of questions that can arise when sequences of specific strata are repeated over and over again. The full-fledged cyclothems in North America are even more thought-provoking. (WRC)

The great coal-bearing cyclothems of the U.S. Interior. Repetitive bedding has been recognized for over a century, as in the case of the remarkable sequence of coal-firelay couplets at South Joggins mentioned above. It was in the American interior, however, where the cyclothem concept was first born. Let us commence with an overview from a paper by G. deV. Klein and D.A. Willard.

‘Cyclic patterns of transgressive-regressive deposition of marine and nonmarine coal-bearing strata are the distinguishing characteristic of Pennsylvanian sedimentation. Udden (1912) and Weller (1930) were the first to recognize such lithological cycles in Pennsylvanian rocks of the Illinois basin; these were arranged into ten members representing nonmarine and marine deposition. Weller (1930) named these cyclic packages ‘cyclothems.’ Later workers recognized this cyclic pattern in the Appalachian basin and in the continental interior of the midcontinent. These Pennsylvanian cyclothems differed from the ideal cyclothem of the Illinois basin; cyclothems in Kansas were characterized by extensive marine deposits, with subordinate coal and sandstone, whereas the cyclothems of the Appalachian basin were dominantly nonmarine, with thick sandstones, thicker coals, and minimal limestone. Later workers recognized three types of cyclothems, known as the Illinois type, the Kansas type, and the Appalachian type.

‘Extensive controversy has existed about the origin of Pennsylvanian cyclothems. Weller advocated a tectonic control for the formation of the cyclothems, whereas Wanless and Shepard (1936) and Wheeler and Murray (1957) argued strongly for a climatically controlled eustatic origin driven by glacial processes that existed during Pennsylvanian time. These glacioeustatic sea-level changes caused shifting of shorelines that were composed primarily of extensive shallow clastic systems that migrated over wide areas. Moore (1950) argued that these sea-level fluctuations which formed cyclothems were tectonically induced by changing volume of ocean basins.’ Klein and Willard contend that North American cyclothems are due to ‘a remarkable coincidence of supercontinent development, concomitant glaciation and eustatic sea-level change, and associated episodic thrust loading and foreland basin subsidence.’ (R34)

– Inner Earth, W. Corliss (1991)