Introduction

Mohenjo-Daro was one of the great cities of the ancient world. Along with its sister city, Harappa, 350 miles to the northeast, it dominated the Indus Valley between 2600 and 1900 B.C. During this period, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa were probably the largest cities in the world. Their reach extended along the Valley for a 1,000 miles. Both Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa are in today’s Pakistan, but their major trading port, Lothal, is located in India. Lothal is noted for its immense artificial “dock” or “harbor.” (MSC9-X2 in Ancient Infrastructure)

Although the existence of Mohenjo-Daro was known to archeologists as early as 1876, it lay unexplored until the early 1920s when major excavations began. (R7) It is easy to understand why this remarkable site was neglected. The climate is terrible. Temperatures can reach 120°F in the summer and drop to freezing in the winter. The scenery is not any better. Today, Mohenjo-Daro is spread out over a salt-covered desert.

But the environs of Mohenjo-Daro were not always so forbidding. Millennia ago, the region was forested; but the trees were felled by the builders of Mohenjo-Daro into order to fire the bricks that make up virtually every structure in the city. In this heavy dependence upon bricks, the buildings of Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, and the lesser cities in the Valley are structurally like the huge pyramids of sun-dried bricks in Peru’s Moche Valley. (MSP1-X3)

In translation, Mohenjo-Daro means “Hill of the Dead.” Strangely for a city that once housed perhaps 40,000 souls in its heyday, only about three dozen skeletons have been found in the ruins. Even more strangely, most of the skeletons were discovered laying unburied in contorted poses. Judging from the bones, these individuals had been cut down by swords and axes. (R3) These skeletons are but one sign that Mohenjo-Daro met a violent end.

Some other curious features of the city that are unrelated to our focus on “structures” are: (1) an absence of offensive weapons (R3); (2) an absence of palaces and temples; and (3) the existence of cylinder seals and other objects bearing stylized symbols. The Mohenjo-Daroans had invented a pictographic sort of script—one that has never been translated. Actually, anthropologists do not even know what language the inhabitants of Mohenjo-Daro spoke or even where the people came from originally. Whoever they were, they were replaced by Aryan invaders circa 1900 B.C. By that time, Mohenjo-Daro may have been mostly a dead city. Archeologists have shown that the city had been plagued by devastating floods and a deterioration of the environment. The Mohenjo-Daroans may have moved on to greener pastures. If so, we do not know where these were.

Mohenjo-Daro Structures

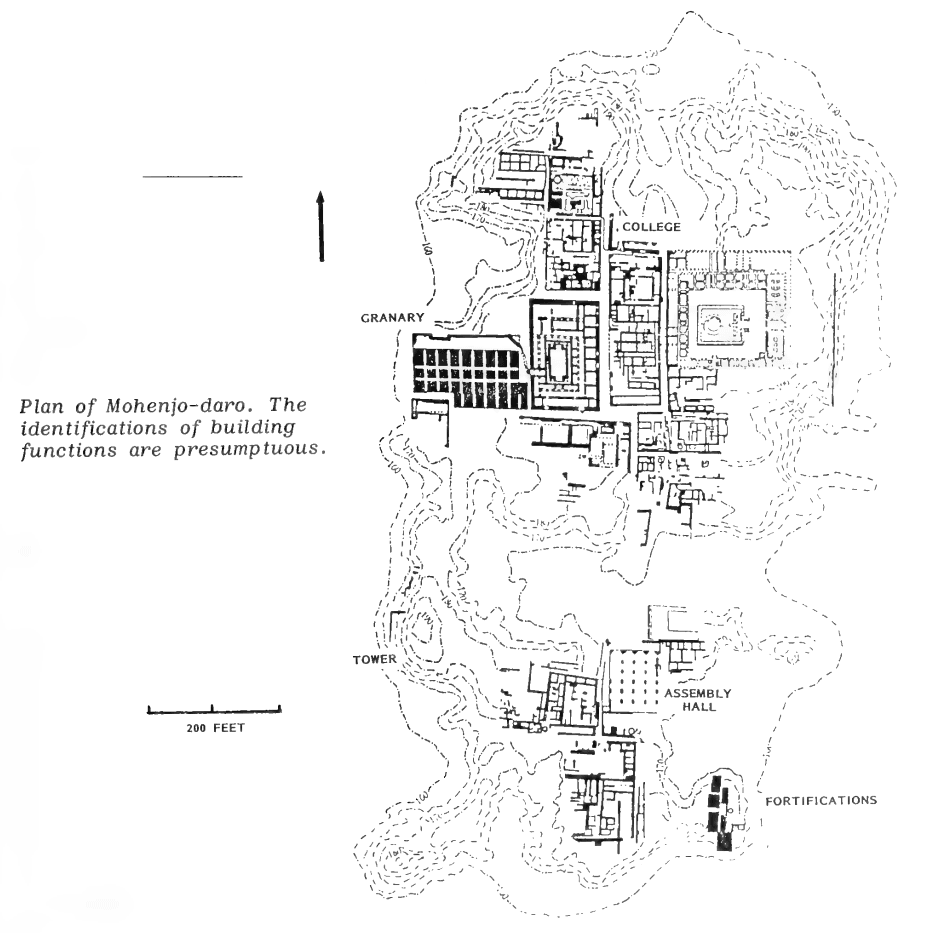

Mohenjo-Daro was neatly laid out on a square grid; it was probably our planet’s first planned city. Twelve, wide main streets of beaten earth all neatly intersected at right angles, or at least pretty close to 90°. The residences were standardized—almost monotonously so. The building codes were very strict, suggesting a strong central government. Because of its regularity, Mohenjo-Daro has been called a “Bronze Age Manhattan.” (R6) While hardly anomalous, this early evidence for systematic city planning is certainly worthy of note.

Even more remarkable, many residences boasted private bathrooms connected to a city-wide drainage system. It was all very precocious.

To serve the populace, the city fathers provided a large communal bath, an assembly hall, and a huge central structure for processing and drying the grain that was grown in the surrounding fields before the climate deteriorated.

Anthropologists suspect that the inhabitants of Mohenjo-Daro were as tightly controlled as the design of the city itself. Mohenjo-Daro seems to have been a very old “Brave New World.”

Mohenjo-Daro’s precociousness and regimentation are remarkable but probably no more so than we see in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. However, two other discoveries said to have been made at Mohenjo-Daro, which, if verified, are highly anomalous. D.H. Childress has mentioned these in one of his “Lost Cities” books. He cites as sources some popular books from the fringes of science. So, caveat emptor!

First, Childress states that some of the unburied skeletons found at Mohenjo-Daro were highly radioactive—“on a par with those at Nagasaki and Hiroshima.”

Secondly, he writes:

Thousands of lumps, christened “black stones,” have been found at Mohenjo-Daro. These are, apparently, fragments of clay vessels that melted together in extreme heat and fused. (R5)

Childress and others speculate that the skeletons and fused objects indicate that Mohenjo-Daro was the target of advanced weapons of some sort 4,000 years before our modern lasers and nuclear weapons. Unfortunately, we do not know the primary sources for these astounding observations.

References

R1. Dales, George F.; “New Investigations at Mohenjo-Daro,” Archaeology, 18:145, 1965. (X0, X1)

R2. Cohen, Daniel; Mysterious Places, New York, 1969, p. 118. (X1)

R3. Furneaux, Rupert; Ancient Mysteries, New York, 1977, p. 90. (X0, X1)

R4. Westwood, Jennifer, ed.; The Atlas of Mysterious Places, New York, 1987, p. 192. (X1)

R5. Childress, David Hatcher; Lost Cities of Ancient Lemuria & the Pacific, Stelle, 1988, p. 74. (X1)

R6. Editors of Time-Life Books; Feats and Wisdom of the Ancients, Alexandria, 1990, p.64. (X1)

R7. Blecher, Wayne R., et al; “Harappa in 3D,” Discovering Archaeology, 1:89, March/April 1999. (X0, X1)

A Facinating Archaeological Mystery

Translated from 2000 A.C: Distruzione Atomica, Ettore Vincenti

Mr. Banerjee’s accidental discovery: he thought he was restoring a temple and found the capital of an ancient civilization – Citizens who are not very religious but love comfort. At this point it is necessary to check whether the deductions that we have drawn so far based exclusively on Vedic texts are compatible or, at least, are not contradicted by archaeological data.

Mr. Banerjee’s accidental discovery: he thought he was restoring a temple and found the capital of an ancient civilization – Citizens who are not very religious but love comfort. At this point it is necessary to check whether the deductions that we have drawn so far based exclusively on Vedic texts are compatible or, at least, are not contradicted by archaeological data.

The ruins of Mohenjo Daro are located near the Indus in Pakistani territory about forty kilometers from the city of Larkana. There is no modern Mohenjo Daro. Apart from the ruins, the only buildings are those of the small and well-kept museum, the Guest-Houses, about ten houses for technicians and officials and the airport building, where planes from Karachi arrive twice a day.

The ruins were discovered almost by chance in 1921 by the Indian archaeologist R.D. Banerjee who had been assigned to study a small stupa (Buddhist temple) dating back to 300 BC. During the excavations Mr. Banerjee discovered that the stupa rested on a much larger and several centuries older building. Shortly thereafter, the archaeologist was murdered in an ambush by bandits while excavating in Northern Pakistan.

The actual excavations at Mohenjo-Daro were begun in 1922 by N. S. Vats and N. K. Dikshit, continued by Sir John Marshall and in 1945 by Sir Mortimer Wheeler. Although only about a quarter of the ancient city has been excavated, we can get a fairly good idea of what Mohenjo Daro looked like and what the daily life of its inhabitants was like.

The actual excavations at Mohenjo-Daro were begun in 1922 by N. S. Vats and N. K. Dikshit, continued by Sir John Marshall and in 1945 by Sir Mortimer Wheeler. Although only about a quarter of the ancient city has been excavated, we can get a fairly good idea of what Mohenjo Daro looked like and what the daily life of its inhabitants was like.

The administrative center was located on a hill about fifty meters high, which was once an island surrounded by the Indus River, as can be easily seen by looking at an aerial photograph, which allows the ancient riverbed to be clearly distinguished. On the hill stands what is commonly referred to as the “citadel” and which includes a large religious building (on which the Buddhist “stupa” rests); the priests’ homes; a Great Ritual Bath; the fortress; the Great Public Granary.

On the smallest arm of the river, which divided the “citadel” from the rest of the city, was the port. It is a very active port, probably the most important existing at the time, a sure sign of intense commercial traffic.

Beyond the port were the residential, commercial and popular neighborhoods. The city has a roughly rectangular urban plan, with straight streets that intersect at right angles. The main ones are wide enough to allow the passage of carts; the others, simple pedestrian alleys. The houses are built with bricks, mostly baked, although there are also those simply dried in the sun. The large quantity of bricks used to build houses, buildings and roads, must have required an enormous quantity of wood for baking. Sir Mortimer Wheeler has even hypothesized that one of the reasons for the progressive decay of the city (detectable by the latest constructions, of a quality decidedly inferior to the oldest) was caused by a continuous worsening of the climate due to a profound alteration of the environment, caused in turn by reckless deforestation to obtain the fuel necessary to bake the bricks. It is a pity that up to now not a single baking furnace has still been brought to light. Unlike what happened in the Babylonian cities, where the maximum architectural effort was concentrated on the construction of palaces, temples, monumental tombs for kings and priests, while the rest of the population lived in primitive houses, in Mohenjo-Daro, the urban planners and architects have evidently made the maximum effort to make the life of the inhabitants comfortable.

With the exception of the one on which the Buddhists built their stupa and the Great Bath, there are no other religious buildings in the city, which, on the other hand, has been equipped with a perfect sewer system, not inferior to modern ones. All the houses, even the most modest, were equipped with a private toilet (with discharge into the main, covered sewer, which passed in the center of the street). The smallest houses had only one floor, to which a second wooden floor was most likely added, while the largest ones, such as the so-called “governor’s palace”, were two or three floors high and were equipped with special tower wells that brought water directly to the upper floors.

With the exception of the one on which the Buddhists built their stupa and the Great Bath, there are no other religious buildings in the city, which, on the other hand, has been equipped with a perfect sewer system, not inferior to modern ones. All the houses, even the most modest, were equipped with a private toilet (with discharge into the main, covered sewer, which passed in the center of the street). The smallest houses had only one floor, to which a second wooden floor was most likely added, while the largest ones, such as the so-called “governor’s palace”, were two or three floors high and were equipped with special tower wells that brought water directly to the upper floors.

While the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside dedicated themselves to cattle breeding and cotton cultivation, the “citizens” were craftsmen and, above all, very skilled traders who travelled as far as Mesopotamia, by sea, and as far as the foothills of the Himalayas, by land. Mohenjo Daro was part of a complex of 144 urban centers, including large and small, probably divided into two kingdoms allied with each other, inhabited by a population of farmers and traders, very active and not inclined to war, as one would be induced to think given the great scarcity of weapons found and their relative crudeness.

All these elements contribute to give us the picture of a very large city for the time (about 30,000 inhabitants), prosperous, well organized from an urban and social point of view, powerful. A city that, after a long period of splendor, experienced one of slow decline, abruptly interrupted by a huge tragedy. A tragedy, it is worth underlining, that filled the inhabitants with such terror that they fled forever. Mohenjo Daro ceased to exist suddenly, and no one has ever tried to rebuild it, despite the very favorable geographical position where it stood.

All these elements contribute to give us the picture of a very large city for the time (about 30,000 inhabitants), prosperous, well organized from an urban and social point of view, powerful. A city that, after a long period of splendor, experienced one of slow decline, abruptly interrupted by a huge tragedy. A tragedy, it is worth underlining, that filled the inhabitants with such terror that they fled forever. Mohenjo Daro ceased to exist suddenly, and no one has ever tried to rebuild it, despite the very favorable geographical position where it stood.

This is the general picture on which everyone, more or less, agrees. The troubles start when you try to get into the details, when you try, that is, to reconstruct everyday life, as it must have been in Mohenjo Daro. What were the daily activities of the inhabitants? What was their language, culture, art, philosophy, religion? These are all mysteries, the blessing and curse of archaeologists, who, based on the scant elements at their disposal, try to give answers, often arriving at conclusions that are in stark contrast with each other. Here is an example, which is not without its own crude humor: during the excavations, a large number of terracotta tablets were found in the shape of squares and triangles with very rounded corners, with carefully rounded edges. According to the most widely accepted theory, these would be what archaeologists, in modest language, define as “pseudo soaps” or “cleaners”; in simpler terms, they were meant to perform the task for which we use toilet paper.

Gabriele Mandel, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Luxembourg, instead suggests that these are ritual objects, used to configure tantric diagrams of constellations. It is difficult to find two more different uses for the same object. The beauty is that there are no elements to resolve the question one way or the other. Leaving the development of theories to those more learned than us, let us limit ourselves to quickly scrolling through the objects that were found during the excavations:

- Pottery: in large numbers, of notable workmanship from both a technical and an aesthetic point of view. There are all sizes, from those over a meter in diameter to those of a few centimeters that were probably used to contain perfumes or balms. Some are decorated, others left natural.

- Tools: these too, quite numerous and of good workmanship. Bronze fishhooks, bronze and bone needles, bronze double axes and stone scrapers and knives.

- Personal objects: evidently the ladies of Mohenjo-Daro cared a lot about beauty and elegance, because several bronze mirrors, bone combs and an infinite number of necklaces, bracelets, buckles made of hard stone, bronze, copper, and, for the poorest, terracotta have been found.

- Seals: they are a predominant characteristic of the culture of Mohenjo-Daro (and of the cities of the Indus Valley in general). They have been found in large quantities and are of excellent workmanship. They are usually square stone tesserae, but there are also rectangular and round ones, which bear sculpted, in negative (i.e. hollowed out), animal figures, or humanoid figures interpreted as deities, or simply some alphabetic characters. By pressing them on the wet clay, you get a positive image. For once, archaeologists agree: the imprint of these seals must have constituted a kind of signature and, at the same time, a guarantee, that merchants and owners affixed to their goods before shipping them or storing them in common warehouses. Although everyone agrees on their use, even these seals (we are in Mohenjo-Daro, don’t forget) contain a little mystery: many of them depict a bovid with a single horn that starts from the center of its forehead. Many are those who have seen in them the image of the famous unicorn of which so many legends speak. Many others maintain, however, that it is a normal ox that seems to have one horn only because it is seen exactly in profile. That is not true, the former object, because when normal oxen and goats are depicted, the two horns are always marked, even if the animal is seen in profile. In one seal, moreover, there is an ox, a goat and a unicorn: the ox and the goat have two horns, the unicorn one, a sign that the artist who made the seal wanted to indicate that the animal had only one. The others reply: where are the remains of the unicorn then? Skeletons of dogs, elephants, oxen, goats, horses have been found, of deer, but not of a unicorn that remains only a figment of the imagination. The question is open.

- Painting: except for the drawings on vases, there is no trace of this form of artistic expression. This does not mean that it was unknown to the inhabitants of Mohenjo-Daro. It may be that their works were executed on perishable material that was completely destroyed.

Games: dice and something very similar to chess for adults. Carts and boats of wood and terracotta for children.

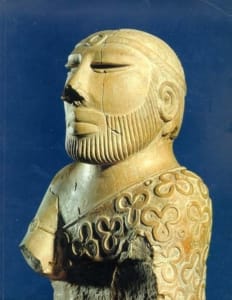

Games: dice and something very similar to chess for adults. Carts and boats of wood and terracotta for children.- Sculpture: all small in size. Many terracotta statuettes in a style that we would define as naive. Much fewer, a dozen or so, those in stone and bronze in a refined figurative style. The bronze one of the dancer and the stone one called the priest-king that has become a bit of a symbol of Mohenjo-Daro are famous. We spoke last of the sculptures because their examination, or rather the examination of the photographs of the very rich catalogue that is included in the Sinhi volumes of the library of the Government Survey of India (the Indian equivalent of the Superintendence of Monuments), reserved us a surprise.

Naturally, the study of the archaeological volumes dedicated to Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Valley was done always keeping in mind the hypothesis (because, at this stage, it was still a hypothesis) that Mohenjo-Daro/Lanka had been destroyed by a sophisticated weapon as described in the wars of the Ramayana.

Among the very few stone sculptures found at Mohenjo-Daro, one immediately appeared to us to be of exceptional interest. It is the piece marked in the catalogue with the number statvary 1505. We have already said that the examples of stone sculpture have markedly figurative characteristics, tending to reproduce with great meticulousness and exactitude the details of the object portrayed. The one we are talking about, a few centimeters high, represents a head entirely covered by a helmet incredibly similar to a modern helmet, complete with visor and reliefs indicating the earphones. The visor, moreover, is painted white to symbolize its transparency.

Among the very few stone sculptures found at Mohenjo-Daro, one immediately appeared to us to be of exceptional interest. It is the piece marked in the catalogue with the number statvary 1505. We have already said that the examples of stone sculpture have markedly figurative characteristics, tending to reproduce with great meticulousness and exactitude the details of the object portrayed. The one we are talking about, a few centimeters high, represents a head entirely covered by a helmet incredibly similar to a modern helmet, complete with visor and reliefs indicating the earphones. The visor, moreover, is painted white to symbolize its transparency.

Archaeologists have classified it as a war helmet. A hasty classification because it does not take into account two very important elements:

- In the entire Indus Valley not a single helmet has been found, neither similar to this one nor any other type.

- This helmet does not have the characteristics of a helmet: it does not have the holes that allow the warrior to breathe, it does not have the joints for the helmet and the visor; instead it has two reliefs at the height of the ears that would be completely useless in a war helmet, indeed even counterproductive, because they would hold the sword blows, preventing the enemy blade from slipping away.

Who or what inspired the unknown sculptor who created this work four thousand years ago? Unfortunately, we are not able to answer this question at the moment. Taken alone, this statuette does not allow us to draw any conclusions. However, it is an interesting piece of the great mosaic that, piece by piece, patiently, relying on experts from the most varied disciplines, we are about to build.

Who or what inspired the unknown sculptor who created this work four thousand years ago? Unfortunately, we are not able to answer this question at the moment. Taken alone, this statuette does not allow us to draw any conclusions. However, it is an interesting piece of the great mosaic that, piece by piece, patiently, relying on experts from the most varied disciplines, we are about to build.