Sweeping mountain arcs, gently bending continental margins, long chains of lakes, curved rift systems, bathymetric arcs on the ocean floor, and even large sedimentary belts all show smooth, coherent curvature over hundreds to thousands of kilometres. These features occur in very different geological settings: some are tectonically active, others passive; some are continental, others oceanic; some are ancient, others geologically young.

The usual explanation for these features is local or regional. Mountain belts are curved because plates collide. Rifts bend because extension propagates unevenly. Sedimentary belts follow basins, rivers, or coastlines. Glacial landscapes reflect ice flow and erosion. In most cases, these explanations are correct — but they are also incomplete.

What is striking is that many of these curved features:

- Extend across multiple geological provinces and lithologies

- Maintain smooth curvature despite very different local conditions

- Persist through multiple tectonic, climatic, or depositional episodes

- Recur with similar geometry on different continents and ocean basins

These observations raise a simple but underexplored question:

Could some of Earth’s large-scale curvature reflect a long-wavelength, planet-scale stress geometry that operates alongside — but does not replace — plate tectonics?

Rather than proposing a new tectonic mechanism, the work asks whether a mathematically defined, global-scale shear geometry leaves detectable geometric and statistical fingerprints in:

- Present-day stress orientations measured around the world

- The long-term curvature of major geological and geomorphic features

The approach is deliberately cautious. It does not attempt to reconstruct specific geological events, nor does it claim to explain plate motions, mantle convection, or orogeny. Instead, it treats global shear as a geometric hypothesis: if such a long-wavelength stress framework exists, then it should leave spatially organized patterns that can be tested statistically and visually.

The central result of the study is subtle but important:

Even when a global shear model does not improve average stress alignment, the spatial pattern of agreement and disagreement is highly organized, coherent, and statistically non-random from regional to near-hemispheric scales.

This distinction — between global alignment and spatial organization — turns out to be critical. It suggests that large-scale structure can be physically meaningful even when simple global metrics fail to detect it.

In the sections that follow, we will:

- Introduce the idea of a planet-scale shear framework and how it is constructed

- Explain how observed stress data are compared to this geometry

- Show how spatial statistics reveal organization invisible to global averages

- Walk through major geological case studies where the same geometry reappears

- Discuss what the results do — and do not — imply about Earth dynamics

The goal is not to replace existing geological explanations, but to explore whether they operate within a broader geometric context — one that may help explain why Earth’s largest curves look the way they do.

A Simple Question: What Would Planet-Scale Shear Look Like?

Before comparing any data, the study begins with a purely geometric question: if Earth were subjected to a long-wavelength rotational shear, what would the resulting surface stress geometry look like?

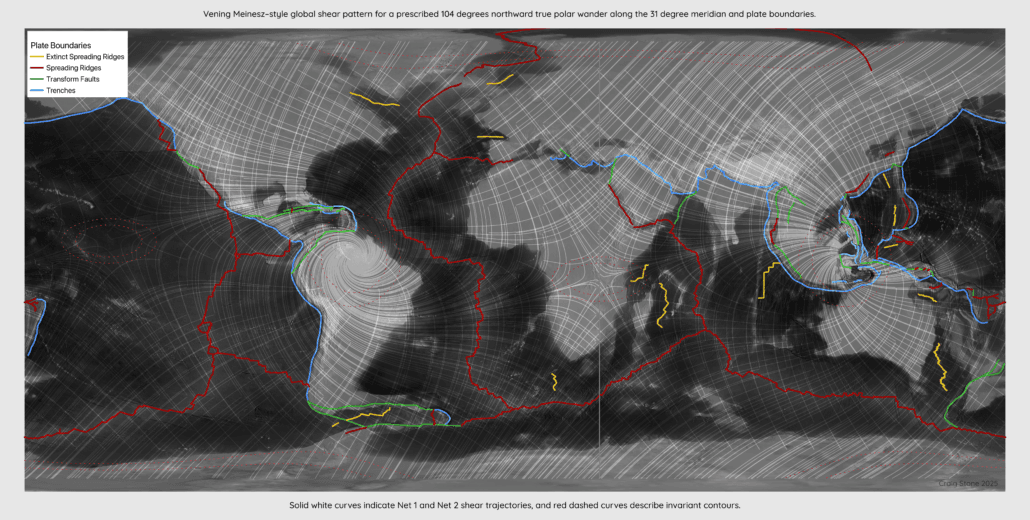

This question is addressed using a classical kinematic approach developed by Vening Meinesz in the mid-20th century to describe deformation associated with large-scale rotations of a spherical shell. The mathematics do not assume plate boundaries, mantle convection cells, or localized forcing. Instead, they describe how a rigid spherical surface responds to a prescribed rotation relative to a fixed reference frame.

In the specific scenario examined in the paper, the Earth’s lithosphere is treated as undergoing a large-amplitude, true-polar-wander–like rotation of approximately 104 degrees about an axis aligned with the 31°E meridian, as described in the Exothermic Core-Mantle Decoupling Oscillation (ECDO) hypothesis. This choice is not presented as a reconstruction of a real event, nor as a claim about Earth history. ECDO’s considerable and growing evidence base provides a convenient, analytically tractable starting point to generate a global, Earth-fixed shear field with long spatial wavelengths.

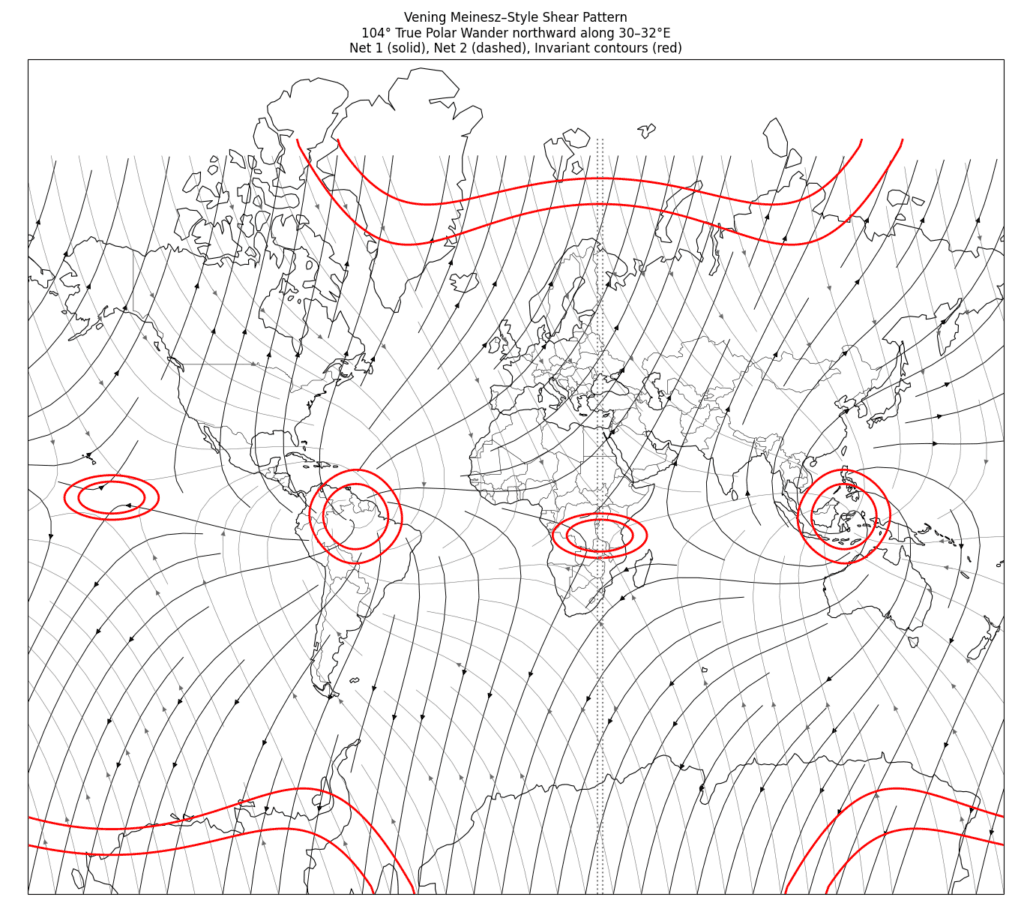

From this rotation, a surface velocity field can be computed everywhere on the globe. Taking the spatial gradients of that velocity field yields a strain-rate tensor at each point on Earth’s surface. The principal directions of this tensor define two orthogonal families of shear trajectories, referred to throughout the paper as Net 1 and Net 2. In addition, there exist special curves where differential shear is minimized; these are called invariant contours.

Importantly, all of these features are derived analytically from the rotation geometry alone. There is no tuning to geological data, no fitting to stress observations, and no optimization to improve agreement. The geometry exists prior to any comparison with the real Earth.

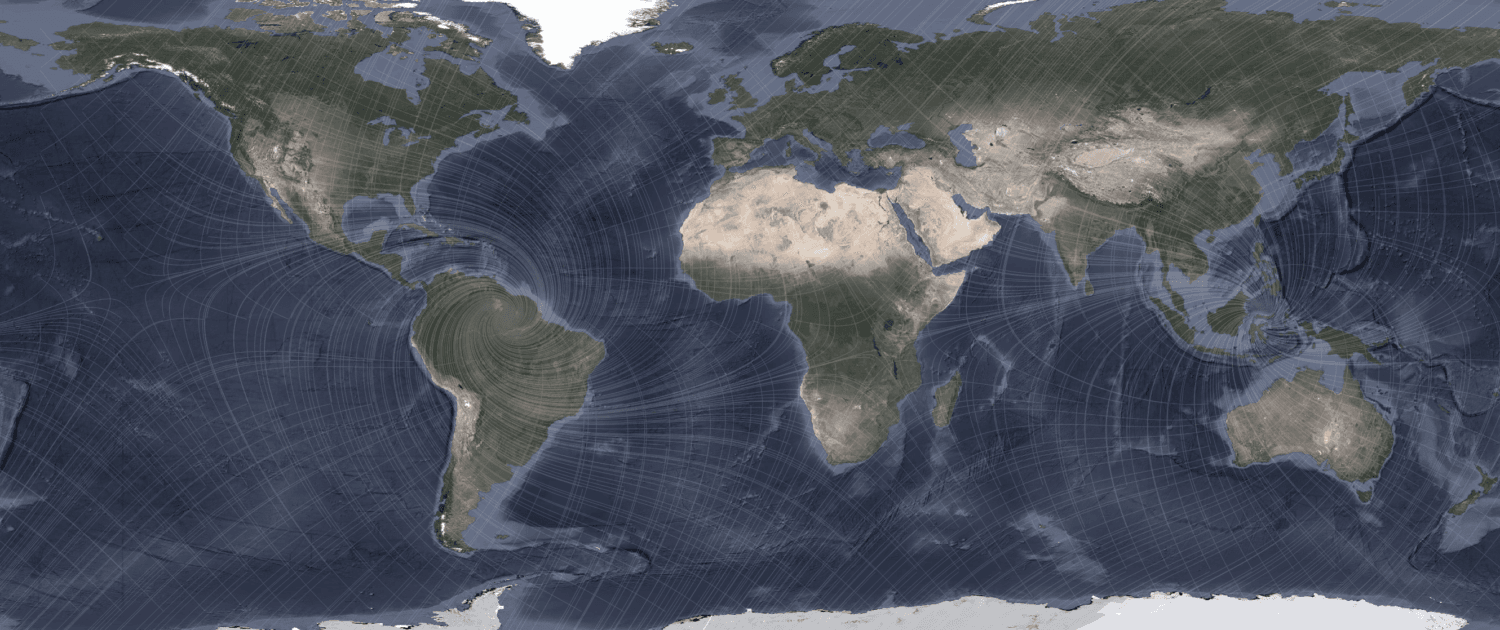

Figure 1 – Analytically derived global shear geometry for a prescribed true-polar-wander–like rotation. Solid curves show one family of shear trajectories (Net 1), dashed curves show the conjugate family (Net 2), and red curves indicate invariant contours where differential shear is minimized.

Several features of this geometry are immediately apparent. The shear trajectories form smooth, continuous curves that span continents and ocean basins. They rotate gradually with latitude and longitude rather than changing abruptly at plate boundaries. The invariant contours trace broad arcs that often resemble the large-radius curvature seen in major geological features.

The two shear families are everywhere orthogonal, creating a global fabric with a built-in directional bimodality. This is significant, because many geological and geomorphic systems show exactly this kind of bimodal orientation: one dominant direction and a conjugate secondary direction, expressed alternately across space.

It is also important to clarify what this geometry does not represent. It is not a model of material flow. It does not describe plates physically sliding along these curves. It does not predict velocities, uplift rates, or stress magnitudes. It is a kinematic framework that describes preferred directions of shear and zones of relative stability or instability under a long-wavelength rotational stress field.

In other words, this is a geometric scaffold. If such a scaffold exists in the real Earth, then local processes — plate convergence, rifting, magmatism, sediment transport, glacial erosion — would still do the work. But they would tend to organize themselves in ways that are biased by this underlying geometry, especially over long time periods and large spatial scales.

The rest of the study asks a straightforward question: does this analytically defined shear framework leave detectable signatures in independent observations of the Earth?

From Geometry to Observation: How Stress Directions Are Tested

To test whether the global shear framework has any relevance to the real Earth, the model must be compared against independent observational data. For this purpose, the study uses the World Stress Map (WSM), an international compilation of present-day stress orientations derived from earthquake focal mechanisms, borehole breakouts, drilling-induced fractures, and other geophysical indicators.

The World Stress Map does not measure stress magnitude. Instead, it records the orientation of the maximum horizontal compressive stress at thousands of locations worldwide. These orientations reflect the integrated response of the lithosphere to tectonic forces, boundary conditions, and longer-wavelength stress fields acting at depth.

At each stress-measurement location, the modeled shear geometry provides two possible shear directions, corresponding to the two conjugate shear families, Net 1 and Net 2. Because stress orientations are axial rather than directional — a line has no inherent “arrow” — all comparisons are performed using 180-degree symmetry. The angular misfit is defined as the smallest angle between the observed stress direction and either of the two modeled shear directions at that location.

This misfit angle ranges from 0 degrees, representing perfect agreement, to 90 degrees, representing complete orthogonality. Under purely random alignment, the expected mean misfit is 45 degrees.

At first glance, one might expect the success of the model to be judged simply by whether it reduces the global average misfit relative to chance. However, this turns out to be an incomplete and potentially misleading criterion. A model can fail to improve the global mean while still capturing meaningful spatial structure.

To make this distinction explicit, the study separates two fundamentally different questions. The first is global alignment: does the model outperform randomly rotated versions of itself when all locations are averaged together? The second is spatial organization: are regions of good or poor agreement clustered geographically in a way that is unlikely to occur by chance?

These questions require different statistical tests and different null hypotheses. To test global alignment, the shear field is randomly rotated about the Earth using Euler rotations. These rotations preserve the internal geometry of the shear net but destroy its fixed alignment with the planet. The observed global mean misfit is then compared to the distribution produced by many such random rotations.

To test spatial organization, the misfit values themselves are randomly permuted among observation locations while keeping the sampling geometry intact. This destroys any geographic structure while preserving the overall distribution of misfit angles. Spatial autocorrelation statistics are then applied to determine whether the observed misfit field is more geographically clustered than expected under randomness.

This separation between alignment and organization is crucial. A geometry that slightly improves alignment everywhere may reduce the global mean but contain little physical structure. Conversely, a geometry that strongly organizes stress directions in some regions but poorly matches others may show no net improvement in the global average while still encoding meaningful large-scale information.

The remainder of the analysis shows that the second case applies here.

When Averages Fail: Detecting Hidden Spatial Organization

When the global shear model is evaluated using a simple average misfit across all stress measurements, the result is unremarkable. The mean misfit falls squarely within the distribution produced by randomly rotated versions of the same geometry. In statistical terms, the model does not outperform chance when judged solely by global alignment.

If the analysis stopped there, the conclusion would be that the model has no explanatory value. However, this conclusion changes completely once spatial organization is taken into account.

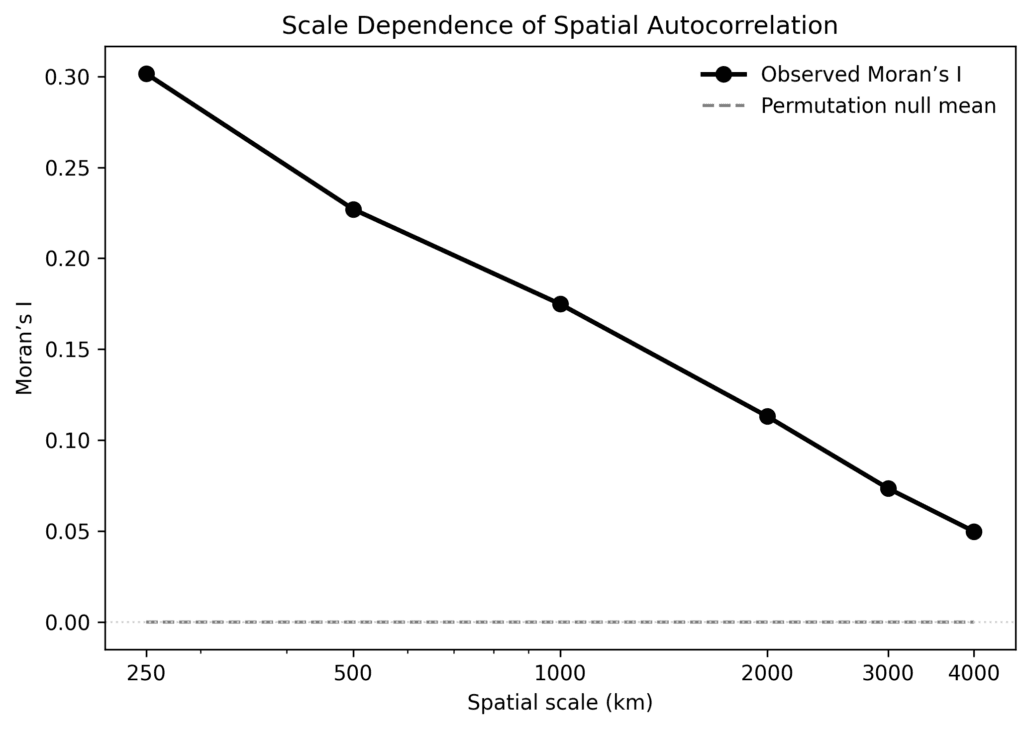

To evaluate spatial structure, the study uses Moran’s I, a standard statistic that measures whether similar values tend to cluster geographically. A Moran’s I value near zero indicates random spatial distribution. Positive values indicate clustering, while negative values indicate spatial dispersion.

Rather than computing Moran’s I at a single scale, the analysis evaluates it across a wide range of spatial neighbourhood sizes, from roughly 250 kilometres to 4,000 kilometres. This allows the detection of structure at regional, continental, and near-hemispheric wavelengths.

At every scale tested, the misfit field shows statistically significant positive spatial autocorrelation. Regions where the model aligns well with observed stress tend to cluster together geographically, as do regions where the misfit is large. This behaviour is extremely unlikely to arise by chance.

The strength of clustering decreases smoothly with increasing spatial scale. At short wavelengths, the organization is strong, reflecting the influence of local tectonic and structural controls. At longer wavelengths, the clustering weakens but remains statistically robust, indicating the presence of a long-wavelength organizing influence extending across continents and ocean basins.

Importantly, there is no abrupt cutoff. Spatial organization does not vanish at continental scales; instead, it decays gradually toward hemispheric dimensions. This behaviour is characteristic of a system with a finite but very large correlation length, rather than one dominated solely by local processes.

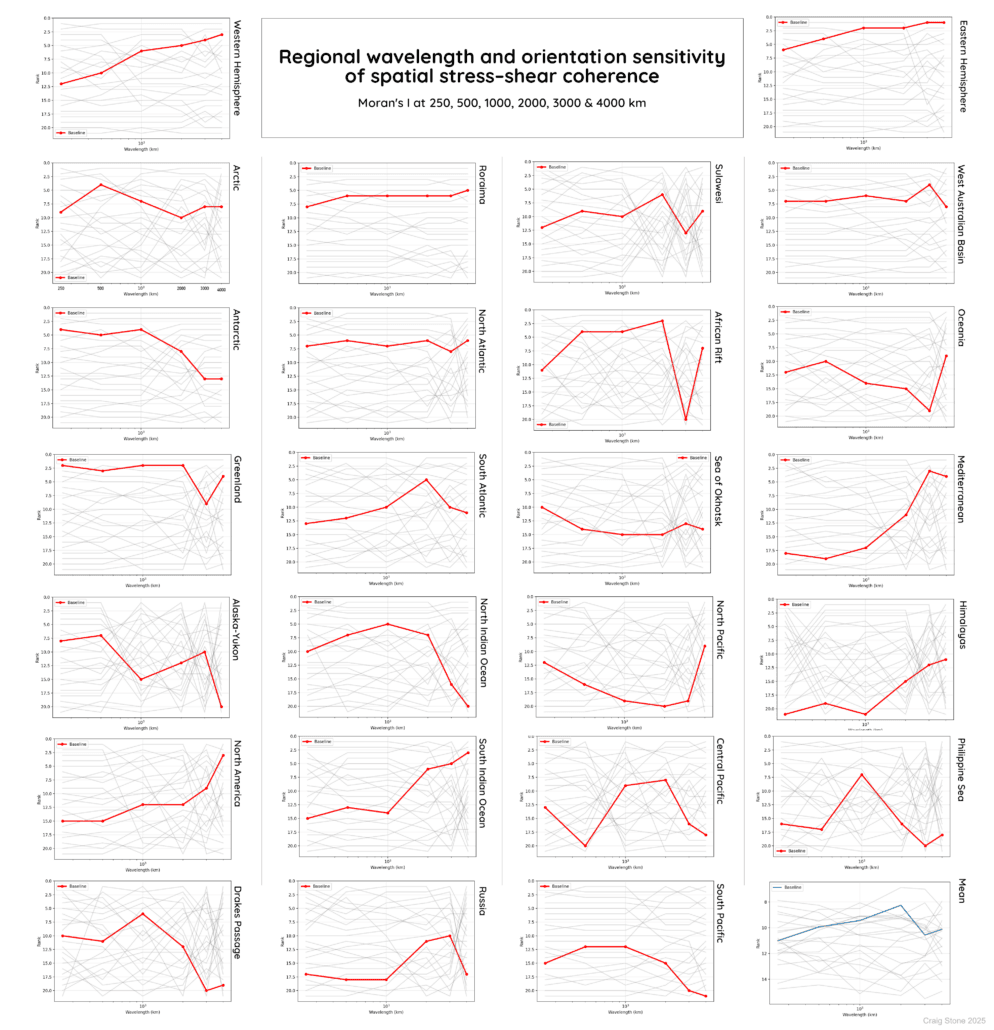

Figure 2 – Scale dependence of spatial autocorrelation in the stress–misfit field. Moran’s I decreases smoothly with increasing spatial scale from regional to near-hemispheric wavelengths, while remaining statistically significant at all tested scales. The dashed line shows the null expectation from random permutation, which remains near zero at all scales.

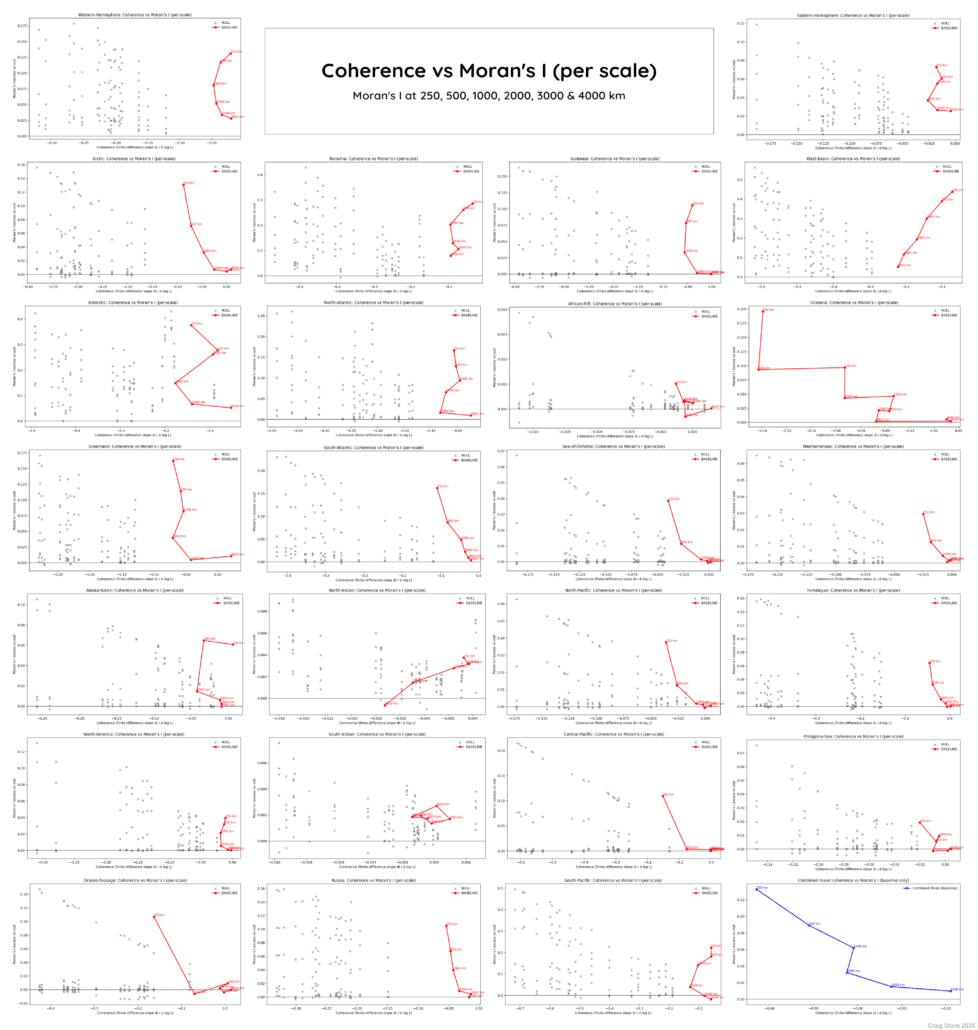

The coexistence of these two results — no improvement in global mean alignment, but strong spatial organization across scales — is the central quantitative finding of the study. It demonstrates that spatial patterning contains information that is invisible to global averages.

In practical terms, this means the shear model does not make stress directions uniformly “better” everywhere. Instead, it captures a structured geographic pattern: some regions align consistently with the modeled geometry, others consistently do not, and these regions are spatially coherent rather than randomly distributed.

This behaviour is exactly what one would expect if a long-wavelength stress framework interacts with, but does not dominate over, regional tectonic processes. Local forces still matter, but they operate within a broader geometric environment that leaves a detectable imprint.

The statistical result therefore justifies a closer look at where, and in what form, this organization appears in the geological record.

A Passive Margin That Isn’t Geometrically Passive

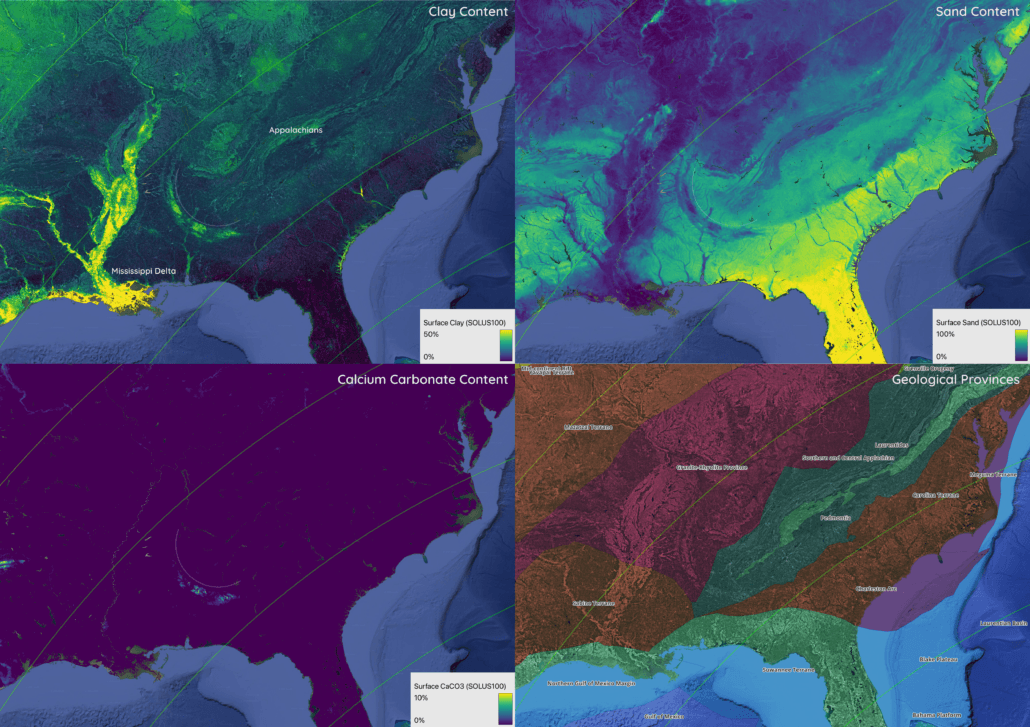

One of the clearest and most accessible examples of large-scale curvature examined in the study is found in the southeastern United States. Across this region, multiple sedimentary datasets reveal a distinct arc just northeast of the Mississippi delta.

This arc is visible independently in clay-rich sediments, carbonate distributions, sandy deposits, and composite geological province maps. Each of these datasets reflects different transport mechanisms, depositional environments, and geological histories, yet they converge on the same sweeping curvature.

Conventional explanations for these patterns emphasize Appalachian orogenic inheritance, differential erosion, river routing, and marine sediment redistribution along a passive continental margin. While all of these processes are unquestionably important, none of them alone predicts why multiple sediment classes should independently trace the same large-radius (~250 km) arc across provinces of very different lithology and age.

When this region is viewed in the context of the global shear framework, the sediment arc aligns closely with invariant shear contours — zones where differential shear is minimized under the modeled rotational geometry. These contours are not tied to present-day coastlines, drainage basins, or tectonic boundaries, yet the sedimentary systems appear to have organized themselves along them.

Figure 3 – Four-panel comparison of clay content, carbonate content, sand distribution, and geological provinces in the southeastern United States. A continent-scale arcuate sediment belt crosses multiple geological provinces and aligns closely with invariant contours of the modeled global shear field.

The significance of this alignment lies in its cross-disciplinary consistency. Clay, carbonate, and sand deposits respond to different hydrodynamic, chemical, and sedimentary controls, yet they converge on the same geometric form. This convergence argues against coincidence and suggests the presence of a shared, long-wavelength organizing influence.

Within the shear-net interpretation, invariant contours represent regions of relative kinematic stability. Over long time periods, such regions would favour sediment accumulation and curvature persistence, while regions of higher differential shear would be more prone to disruption, reworking, or segmentation.

The southeastern sediment arc therefore acts as a geomorphic and sedimentological recorder of an inherited stress geometry. Repeated cycles of erosion, sea-level change, and deposition appear to have amplified rather than erased this curvature, consistent with the idea that long-wavelength stress organization can persist through multiple geological regimes.

This interpretation does not displace standard passive-margin models. Instead, it embeds them within a hierarchical framework in which local processes operate inside a broader geometric context that helps explain why certain forms persist and recur.

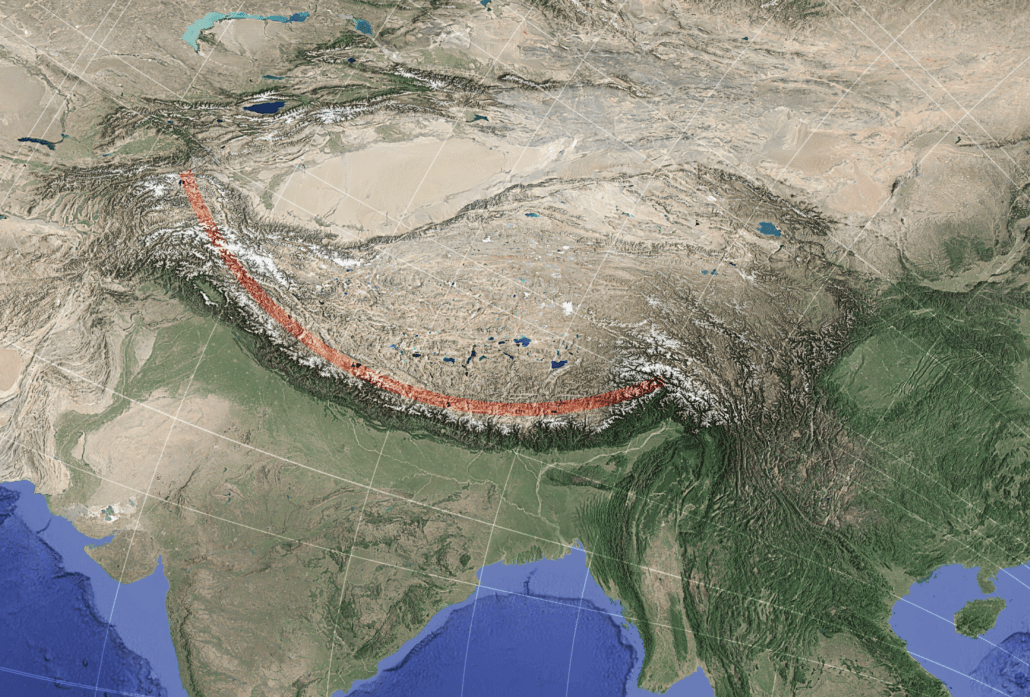

Why Is the World’s Highest Mountain Belt So Smoothly Curved?

The Himalayan mountain belt is among the most intensively studied tectonic features on Earth. Its formation is firmly linked to the collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates, producing crustal shortening, thickening, and uplift over thousands of kilometres.

While plate convergence explains the existence of the Himalaya, it does not by itself explain the remarkable geometric regularity of the arc. Over more than 2,500 kilometres, the belt maintains a smooth, continuous curvature with few large-scale deviations.

In the global shear framework, the Himalayan arc occupies a transition zone where the two conjugate shear families rotate smoothly along strike. One family lies approximately parallel to the arc, while the other remains nearly orthogonal. This configuration creates a mechanically coherent setting in which shortening can be expressed as a laterally continuous curve rather than as segmented or irregular structures.

Figure 4 – The Himalayan mountain belt forms a smooth, continent-scale arc that lies approximately parallel to one modeled shear family and orthogonal to the conjugate family.

In this view, collision provides the force, but the long-wavelength stress geometry biases how that force is expressed spatially. Rather than dictating tectonic behaviour, the shear framework acts as a geometric filter that favours large-radius curvature where the shear field is stable and smoothly varying.

This perspective aligns with the broader statistical result of the study: regions of coherent curvature tend to occur where the modeled shear geometry varies gradually, while segmentation and complexity increase where the shear trajectories rotate rapidly or intersect.

The Himalayan arc is therefore not treated as evidence for a global shear field in isolation, but as one example of how strong local tectonic forcing can interact with a longer-wavelength geometric environment to produce persistent, large-scale form.

When Curvature Appears Where Inheritance Is Minimal

If large-scale curvature were primarily the result of continental inheritance or long-lived crustal structures, then oceanic regions — where lithosphere is continuously created and recycled — should display far less coherence. One of the strengths of the shear-net framework is that it can be tested in exactly these environments.

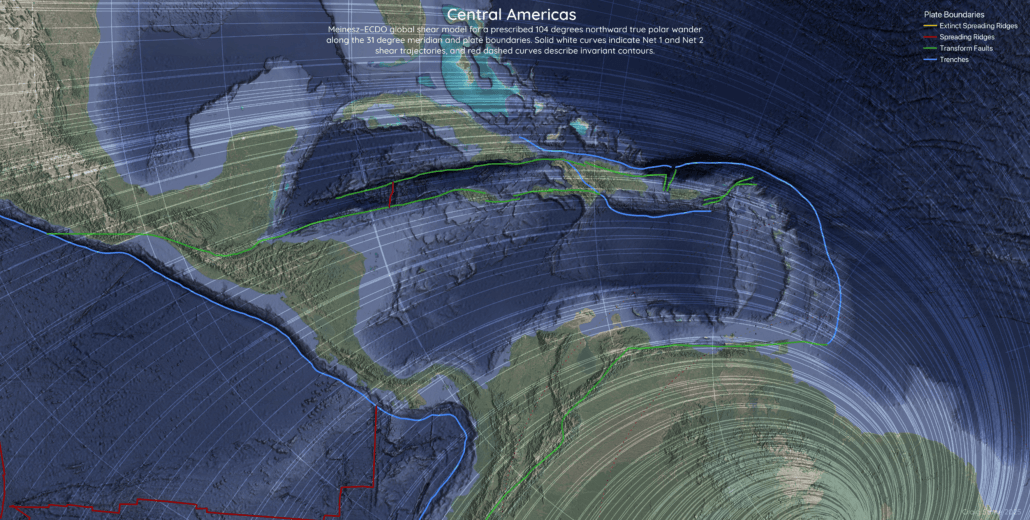

The Caribbean and Central America

The Caribbean region is shaped by subduction, strike-slip motion, slab rollback, and microplate interaction. Arc curvature and segmentation vary strongly along strike, reflecting local kinematics and inherited structure. Despite this complexity, several major arc segments align closely with the modeled shear trajectories.

In the shear framework, curved forearc and intra-arc basins tend to occupy regions where one shear family remains locally stable over distances of 1,000 to 1,500 kilometres, while the conjugate family rotates more rapidly. In contrast, regions dominated by transform motion and oblique convergence correspond to zones of higher stress–misfit and rapid shear rotation.

Figure 5 – Central America and the Caribbean showing geometric correspondence between arcuate plate boundaries and the modeled global shear field.

This pattern suggests that while subduction and strike-slip processes control deformation, the geometric form of curvature and segmentation is influenced by a longer-wavelength stress environment.

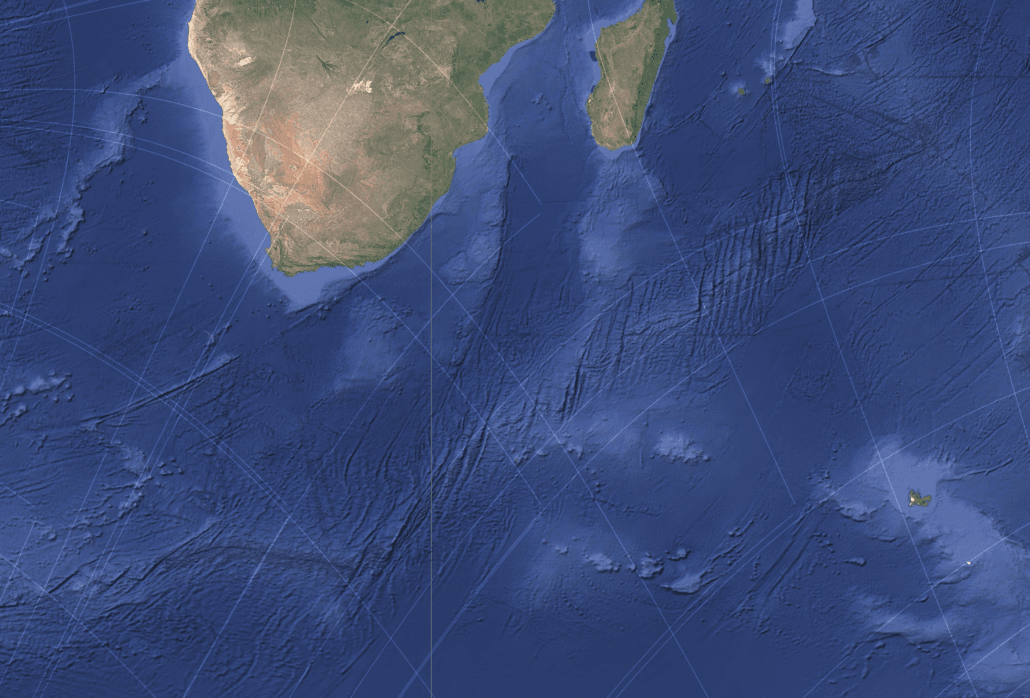

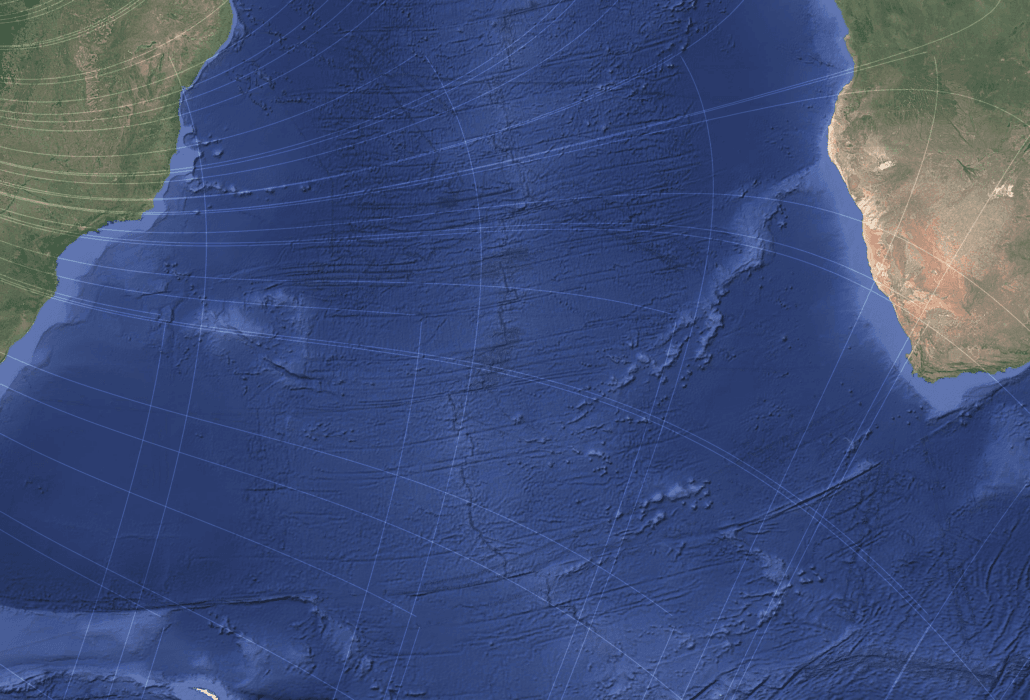

The South Indian Ocean Tectonic Arc

One of the most striking features examined in the study is a vast, gently curving tectonic arc spanning large portions of the southern Indian Ocean. This feature crosses abyssal plains, intersects multiple spreading systems, and persists across regions with very different spreading histories.

In the global shear framework, this arc aligns closely with invariant shear contours. These contours remain fixed relative to the planet, meaning that successive generations of oceanic lithosphere are created within the same geometric environment.

Figure 6 – A large-scale tectonic arc in the southern Indian Ocean showing strong alignment with invariant contours of the modeled shear field.

Ridge segments within this region tend to rotate smoothly to remain orthogonal to nearby shear trajectories, while transform faults often align parallel to one of the shear families. This behaviour mirrors patterns seen along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and suggests that ridge segmentation and propagation are biased by externally imposed geometry rather than being purely local phenomena.

The diagnostic value of this example lies in its oceanic context. With minimal continental inheritance, the persistence of coherent curvature strongly supports the presence of a long-wavelength organizing influence.

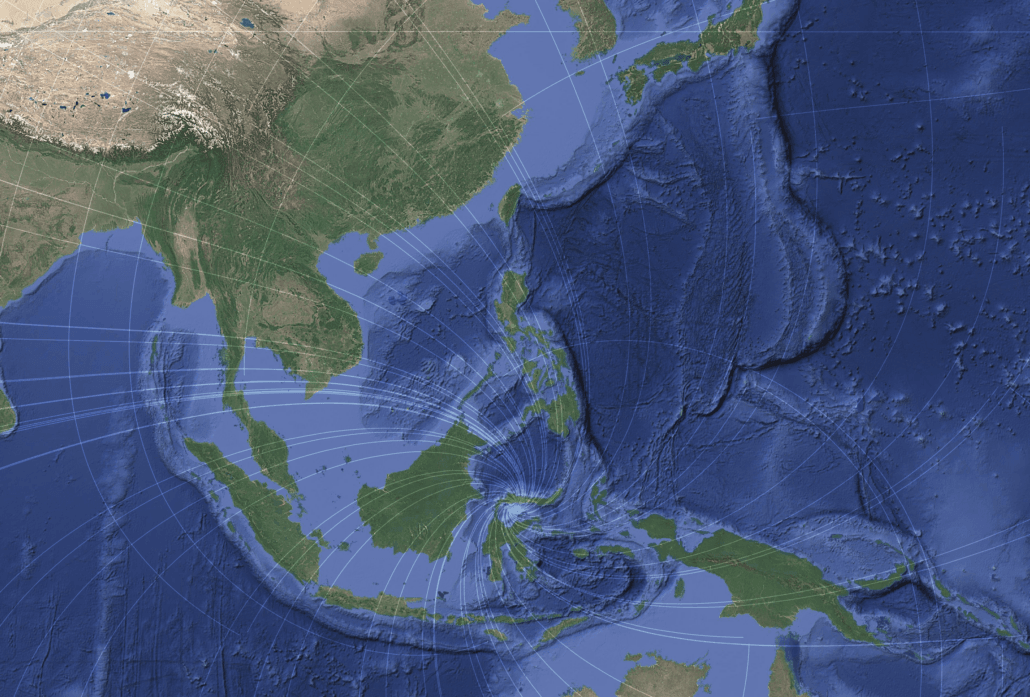

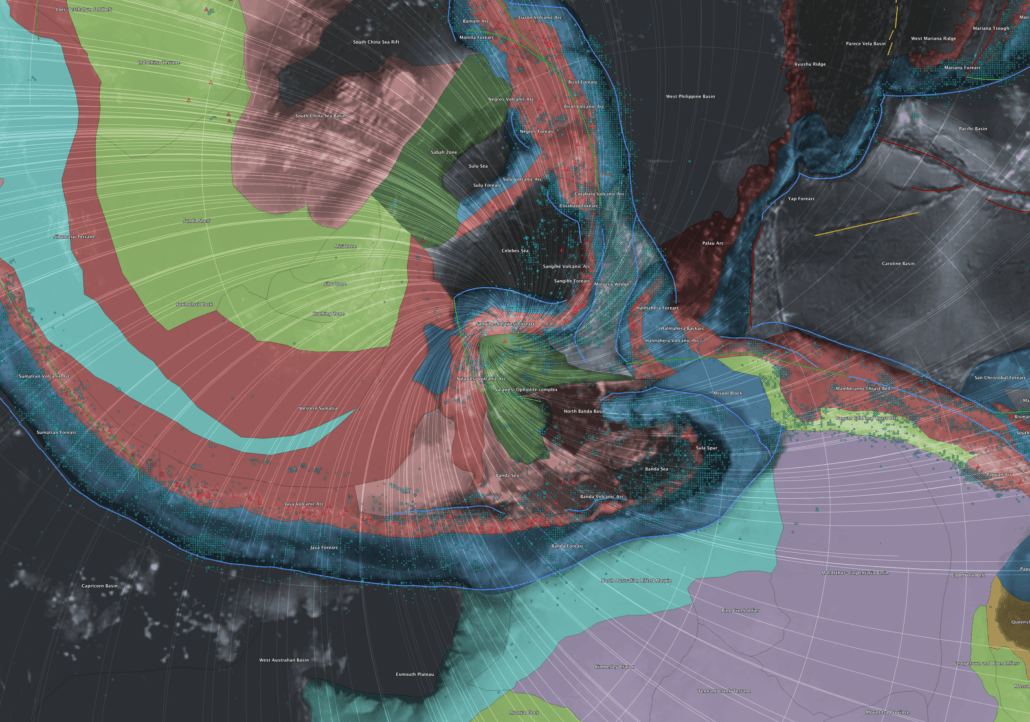

The Banda–Sulawesi Arc System

The Banda–Sulawesi region is among the most geometrically complex tectonic systems on Earth, involving arc–continent collision, slab rollback, and large rotations of crustal blocks. Many studies attribute its extreme curvature to progressive rotation driven by convergent dynamics.

Within the shear framework, the Banda Arc follows a path close to one of the modeled shear trajectories, while structural terminations approach invariant-contour regions. The two shear families rotate rapidly in this region, creating a geometric environment that supports sustained curvature even as local kinematics change.

Figure 7 – Primary and secondary bathymetric arcs near Sulawesi aligned with predicted shear trajectories.

This interpretation does not replace rotation-based models, but helps explain why curvature persists and remains smooth through multiple tectonic phases.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge provides another important test case. Its segmentation, transform offsets, and alternating ridge orientations are usually explained by spreading kinematics and thermal structure.

When viewed in the context of the modeled shear geometry, ridge segments alternate between alignment with Net 1 and Net 2 shear families along strike. This alternation is expressed across both hemispheres and at multiple spatial scales.

Figure 8 – The Mid-Atlantic Ridge exhibits alternating alignment with the two conjugate shear families along its length.

As with continental rifts, spreading remains the dominant process, but the form of segmentation appears biased toward orientations that are geometrically compatible with a long-wavelength stress field.

When Curvature Persists Far from Plate Boundaries

Large-scale curvature is not confined to plate margins. Some of the most revealing expressions of the shear framework occur within continental interiors, where deformation is distributed, episodic, or dominated by surface processes such as glaciation and sedimentation.

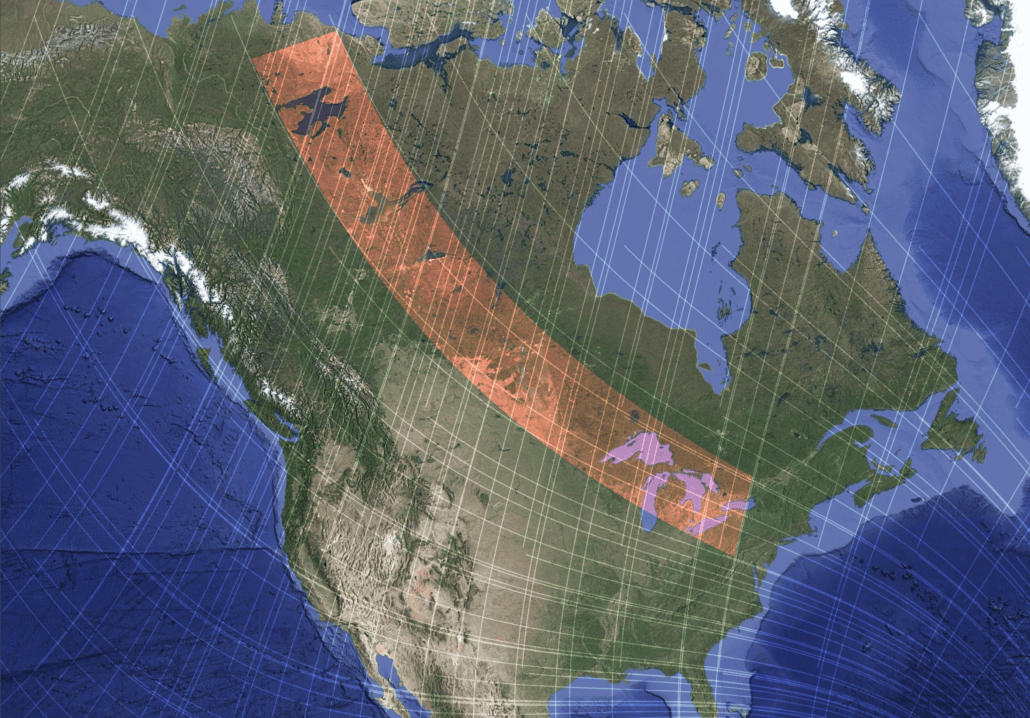

North American Intracontinental Basins and Lake Chains

Across North America, a broad arc of large lake basins extends from the western interior through the Great Lakes and into the North Atlantic realm. Individual basins are usually explained in terms of glacial erosion, flexural subsidence, and lithospheric inheritance, yet their collective geometry forms a smooth, continent-scale curve.

In the shear framework, this lake chain aligns closely with invariant contours, indicating long-term curvature stability. Basin margins and interconnecting depressions alternate in alignment between the two shear families, producing a coherent directional pattern across thousands of kilometres.

Figure 9 – A continent-scale arc of major lakes and basins across North America aligned with invariant shear contours.

Glacial processes provided the erosional energy needed to excavate these basins, but the shear framework offers an explanation for why basin geometry and alignment recur systematically rather than randomly across the continent.

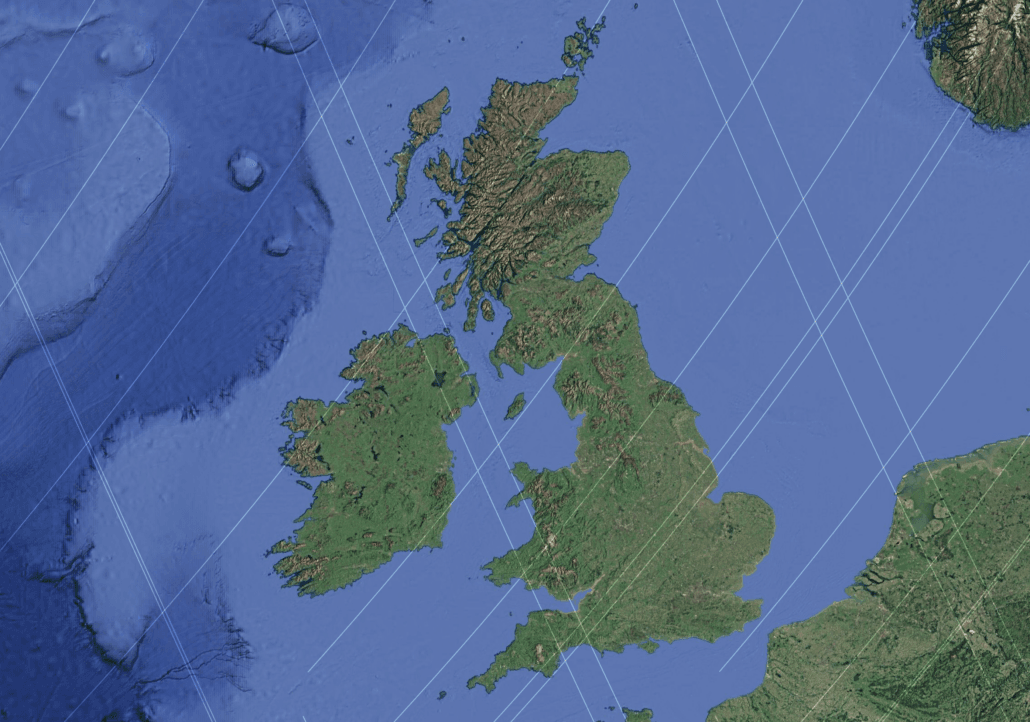

British and Irish Geomorphic Bimodality

Britain and Ireland display a striking bimodality in landscape orientation. Valleys, drainage networks, structural lineaments, and glacial features tend to fall into two dominant directional sets that alternate across space.

When compared with the modeled shear geometry, these directional sets correspond closely to the two conjugate shear families. Regions of persistent curvature and valley continuity coincide with predicted low-shear domains, while abrupt directional switching occurs near zones of rapid shear rotation.

Figure 10 – Bimodal geomorphic and structural orientations in the United Kingdom, particularly Scotland, corresponding to the two modeled shear families.

Glacial erosion, fluvial incision, and tectonic reactivation remain the proximate causes of landscape evolution, but the shear framework helps explain why certain orientations are preferentially preserved and repeatedly re-excavated over multiple climatic cycles.

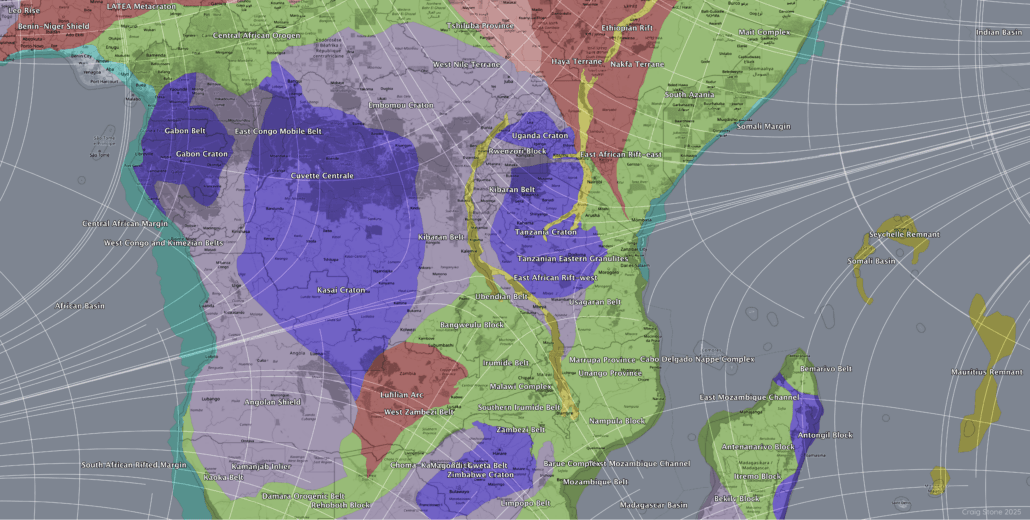

The East African Rift System

The East African Rift System is a classic example of continental extension, yet its geometry varies markedly along strike. Straight segments alternate with sweeping arcs and bifurcations.

Within the shear framework, the major rift corridors lie in regions where one shear family remains approximately parallel to the rift axis while the conjugate family rotates across the margin. Arcuate rift segments occur where the two families converge or rotate rapidly.

Figure 11 – Double-arc geometry of the western East African Rift coinciding with convergence of the two shear families near 14°S, 31°E.

Extension and magmatism drive rift formation, but the long-wavelength stress geometry appears to bias how rift curvature and segmentation are expressed spatially.

Curvature, Basins, and Shear Corridors at the Top of the World

High-latitude regions provide a particularly strong test of the shear framework because they combine ancient lithosphere, repeated glaciation, and long-lived structural inheritance. In these settings, any persistent geometric organization is unlikely to be the result of short-lived tectonic events alone.

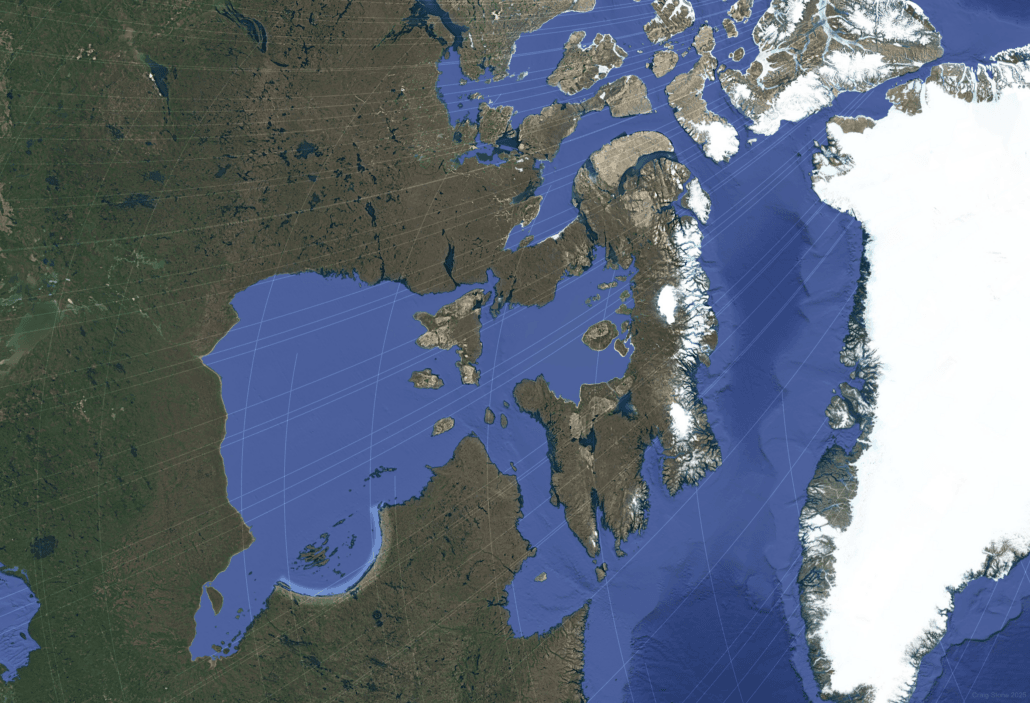

Greenland and the Hudson Bay Region

The Greenland–Hudson Bay sector records a complex history of Precambrian craton assembly, lithospheric stabilization, repeated glacial loading and unloading, and intracontinental basin development. The Hudson Bay depression, including the arcuate Nastapoka structure along its southeastern margin, is commonly attributed to glacial erosion and flexural response of the crust.

When examined within the global shear framework, major basin margins, structural corridors, and lineament sets in this region align preferentially with one or both shear families. Zones of curvature stability coincide with predicted low-shear domains, while regions of structural dispersion occur where the shear trajectories rotate more rapidly.

Figure 12 – Greenland and Hudson Bay in polar stereographic projection showing bimodal agreement with the modeled shear families and the arcuate Nastapoka structure.

Glacial processes clearly shaped the landscape, but the shear framework offers a coherent explanation for why basin geometry and curvature persist across structurally heterogeneous crust and multiple glacial cycles.

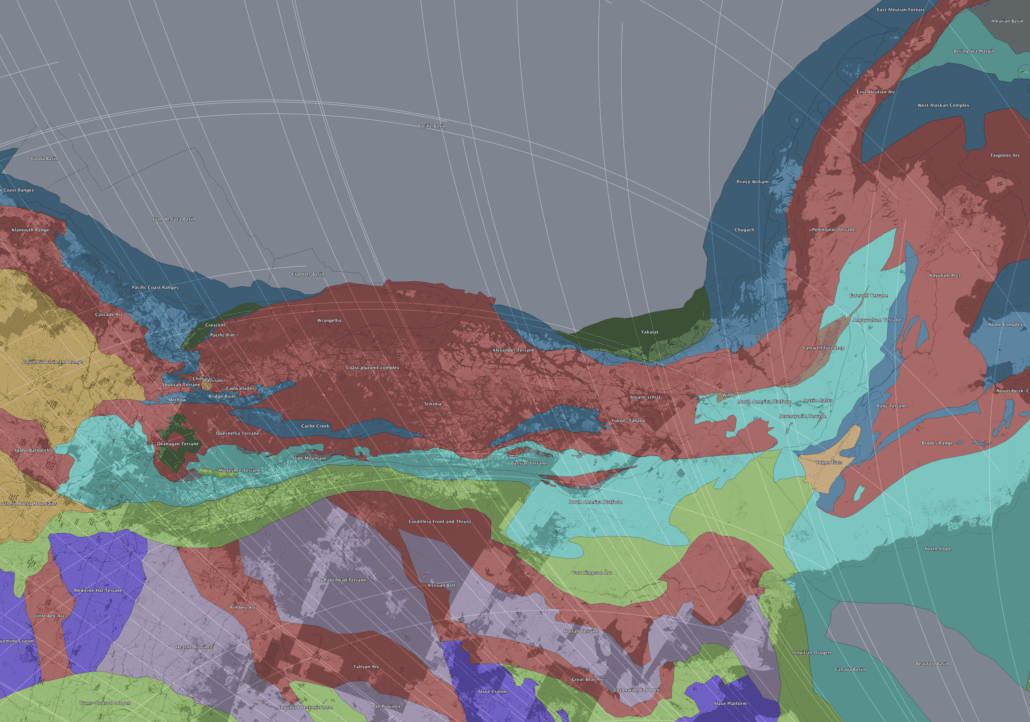

Northwestern Canada and the Fort Simpson Arc

Northwestern Canada hosts the Fort Simpson Arc anomaly, traditionally interpreted as an Early Proterozoic magmatic arc based on geochronology, aeromagnetic signatures, and gravity anomalies. While this interpretation explains the timing and composition of magmatism, it leaves several geometric questions unresolved, particularly the broad curvature, bifurcation, and repeated reactivation of the structure.

In polar projections, the Fort Simpson Arc aligns closely with one branch of the modeled global shear net. Its curvature, internal segmentation, and westward broadening correspond to regions where shear trajectories converge and rotate. This correspondence is independent of stratigraphy or magmatic age.

Figure 13 – Northwestern Canada showing alignment of the Fort Simpson Arc and adjacent structures with modeled shear trajectories.

Within the shear-net interpretation, Proterozoic arc magmatism is viewed as one expression of a pre-existing lithospheric shear corridor rather than its cause. Such corridors would localize magma ascent during favourable stress regimes and remain mechanically weak and prone to reactivation over billions of years.

This perspective resolves several long-standing ambiguities: the elliptical geometry of the anomaly, its apparent continuity despite geological heterogeneity, and its repeated reuse during later tectonic and extensional events.

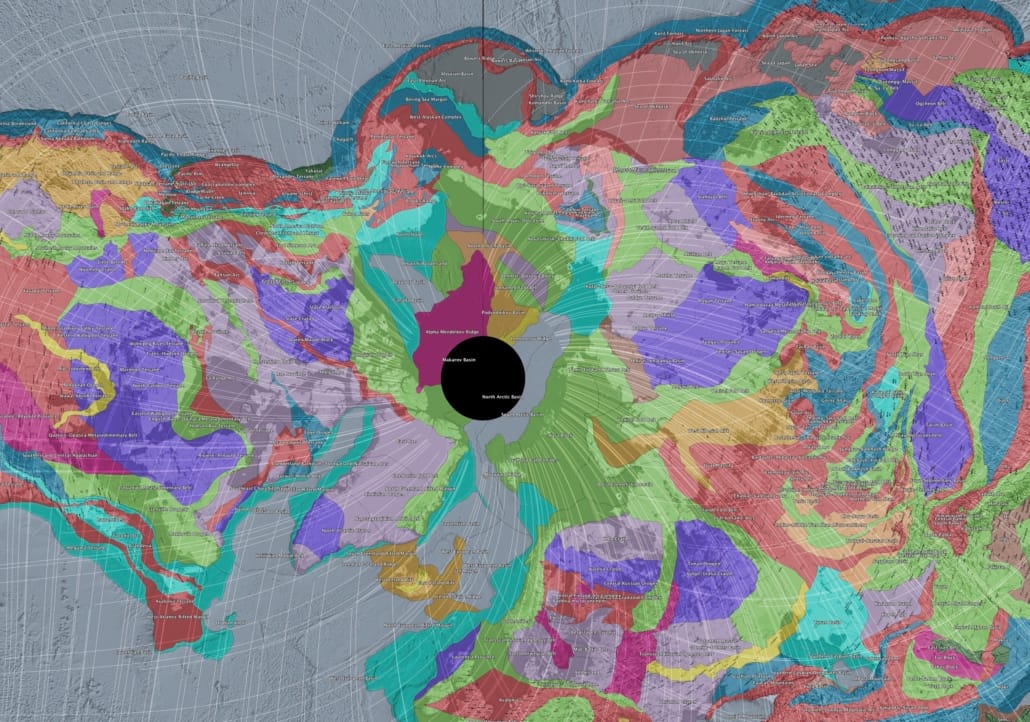

The Circum-Arctic Synthesis

When the Arctic is viewed as a whole, the coherence of the shear framework becomes even more apparent. Large-radius curvature in continental margins, shelf edges, submarine ridges, and basin boundaries across North America, Greenland, and Eurasia show repeated alignment with the modeled shear trajectories.

Figure 14 – Arctic polar projection showing global shear trajectories overlaid on tectonic and geological provinces. Major circum-Arctic structures align with the modeled shear field across continents.

Figure 15 – Arctic polar projection of shear trajectories over satellite imagery and bathymetry, highlighting alignment with coastal arcs, shelf edges, and submarine structures.

These correspondences do not imply that the shear field generated Arctic geology. Rather, they suggest that rifting, sedimentation, and glaciation have operated within a persistent geometric environment that conditions where curvature is stable and where segmentation occurs.

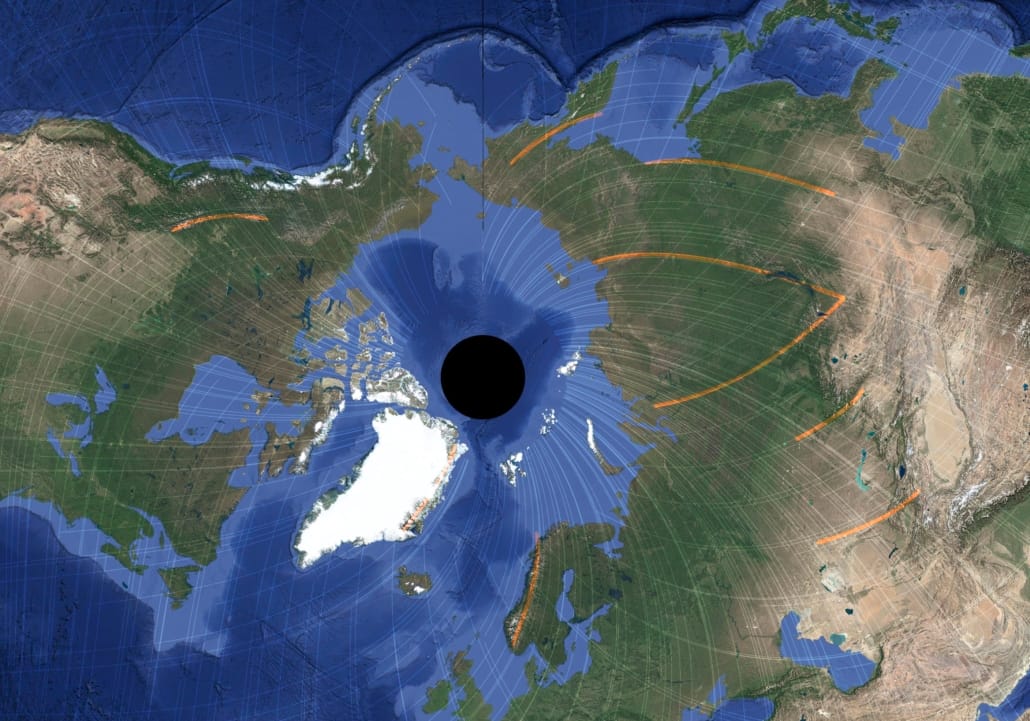

How the Shear Framework Interacts with Active Plate Tectonics

Up to this point, most examples have focused on curvature expressed in geological form. A complementary test is to examine how the global shear geometry relates to modern plate boundaries, seismicity, and volcanism. This comparison helps clarify whether the framework is merely a visual overlay or whether it interacts meaningfully with active deformation.

When plate boundaries are plotted alongside the modeled shear trajectories, a striking degree of geometric correspondence emerges across subduction zones, transform faults, extinct ridges, and continental rifts. This correspondence does not imply control or causation, but it does indicate that plate-scale deformation often organizes itself tangentially or orthogonally to the same long-wavelength geometry.

Figure 16 – Comparison of the modeled global shear field with modern plate boundaries. Strong geometric correspondence is observed across subduction arcs, transforms, and extinct spreading systems.

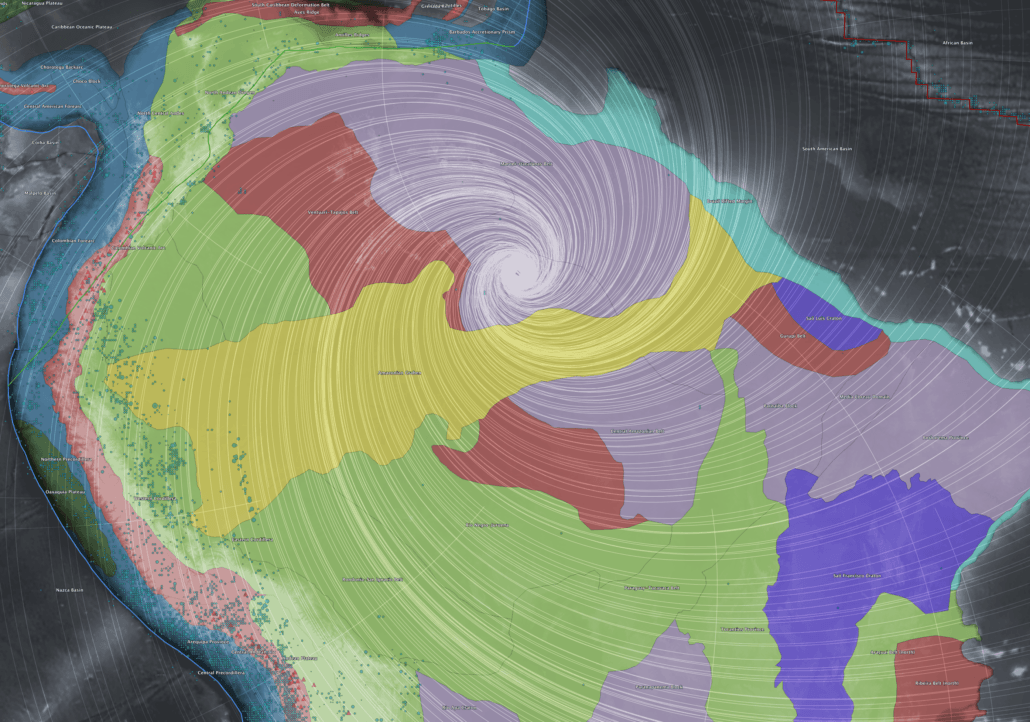

A particularly useful way to examine this relationship is by comparing the two Euler-point regions defined by the prescribed rotational geometry. These regions represent areas where the shear trajectories tighten into spiral patterns around opposite sides of the globe.

The Western Euler Domain

The western Euler domain, centered over northern South America and the Caribbean, shows exceptionally strong correspondence between the shear framework and observed geological structure. In this region, shear trajectories run parallel to Precambrian cratonic margins, mobile belts, and long-lived deformation zones. Earthquake epicenters and volcanic centers cluster preferentially along shear-parallel paths.

Figure 17 – Western Euler-point domain showing shear trajectories over geological provinces, plate boundaries, earthquake epicenters, and volcanic centers.

The consistency between ancient structures and present-day deformation suggests that thick continental lithosphere can preserve and repeatedly express low-order global stress modes over geological time.

The Eastern Euler Domain

The eastern Euler domain, located in the Indonesia–Sunda–Banda region, is tectonically far more complex. Rapid convergence, slab rollback, arc–continent collision, and back-arc extension dominate the region. Despite this complexity, major arcuate subduction systems still follow curvature consistent with the modeled shear trajectories.

Figure 18 – Eastern Euler-point domain illustrating the relationship between shear trajectories, arcuate subduction systems, seismicity, and volcanism.

In this domain, the shear framework acts less as a preserved fabric and more as a geometric constraint within which rapidly evolving tectonic processes organize themselves. The contrast between the two Euler domains highlights the role of lithospheric memory in amplifying or obscuring long-wavelength stress organization.

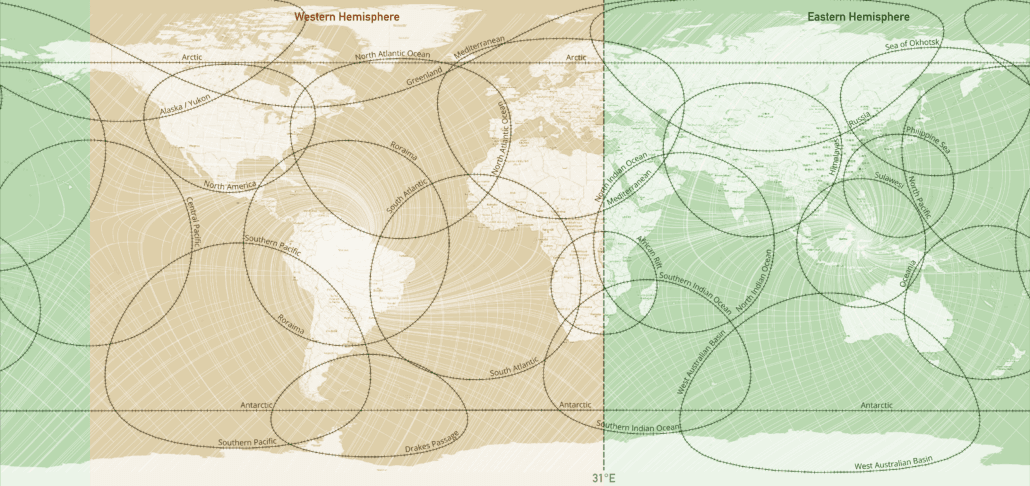

From Pattern Recognition to Statistical Necessity

A common concern with global geometric interpretations is that apparent alignments may reflect confirmation bias or the human tendency to see patterns. This is precisely why the statistical component of the study is essential.

The permutation-based Moran’s I analysis demonstrates that the spatial organization of stress–misfit values is not a visual artefact. At every tested scale from 250 to 4,000 kilometres, the observed clustering exceeds what would be expected from random spatial arrangements by a wide margin.

Figure 19 – Geographic distribution of the sampled regions.

Crucially, this organization persists even though the global mean misfit is statistically indistinguishable from chance. This combination of results is difficult to produce accidentally. Random geometries may occasionally reduce global misfit or produce local alignment, but they do not generate coherent, scale-dependent spatial structure across the entire planet.

The smooth decay of spatial autocorrelation with increasing scale further argues against artefacts of sampling density or regional clustering. Instead, it points to a real correlation length on the order of thousands of kilometres, consistent with a planetary-scale organizing influence.

In short, the statistics show that something systematic is present in the data, even if it is not optimized for global alignment.

Figure 20 – How different regions respond to scale when compared with the shear model.For each major geographic region, the strength of spatial clustering is evaluated at increasing wavelengths, from regional to near-global scales. The red curves show the behaviour of the shear-net model, while the grey curves show randomly rotated reference cases. Regions where the red curve forms a smooth or plateauing trend indicate consistent, scale-dependent organisation, whereas noise-like behaviour would appear erratic. This demonstrates that several regions respond coherently to the same long-wavelength geometry.

Figure 21 – Relationship between spatial clustering and geometric coherence across scales. Each panel compares how strongly the stress–shear misfit clusters spatially against how geometrically coherent that clustering is at a given scale. Grey points represent random reference cases; red curves show the shear-net solution. The blue curve summarises the global mean behaviour. The separation between the red and grey trends indicates that the observed spatial structure is not a by-product of random alignment, but reflects a systematic, scale-consistent pattern.

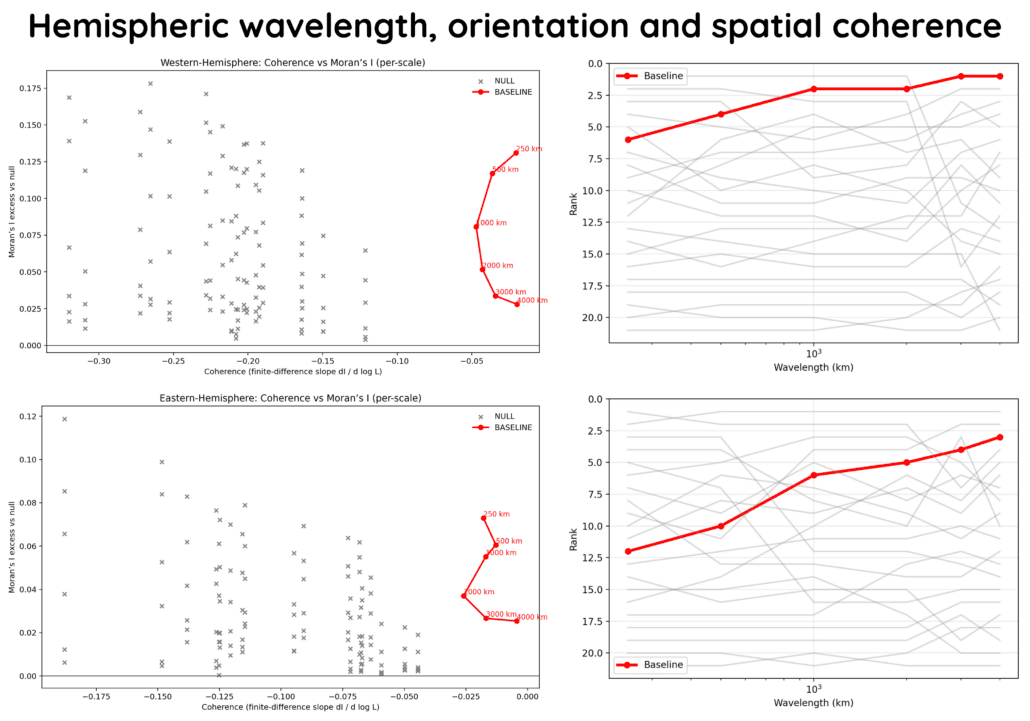

Figure 22 – Hemispheric comparison of large-scale stress organisation. This figure shows the same spatial-statistical analysis performed independently for the Western and Eastern hemispheres. In both hemispheres, the shear-net solution follows a distinct trajectory compared to random reference cases, especially at wavelengths of 1,000–4,000 km. The result demonstrates that large-scale organisation is not confined to a single region or dataset, but emerges independently in both hemispheres, consistent with a planet-scale stress topology.

Testing the Shear Framework Against Mantle Anisotropy

Geological curvature and present-day stress orientations provide indirect evidence for long-wavelength organisation in the Earth system. A more stringent and independent test comes from seismic anisotropy, which probes deformation preserved within the upper mantle itself. In particular, SKS shear-wave splitting measurements offer a global dataset of mantle fabric that is largely decoupled from surface geology and short-term tectonic processes.

When a shear wave generated by a distant earthquake passes through anisotropic mantle material, it splits into two orthogonally polarised waves that travel at slightly different speeds. The orientation of the fast polarisation direction reflects the dominant alignment of minerals, cracks, or fabrics within the upper mantle, typically interpreted as the cumulative result of long-term deformation. Importantly, these orientations are axial: a fast direction of 30° is physically equivalent to 210°.

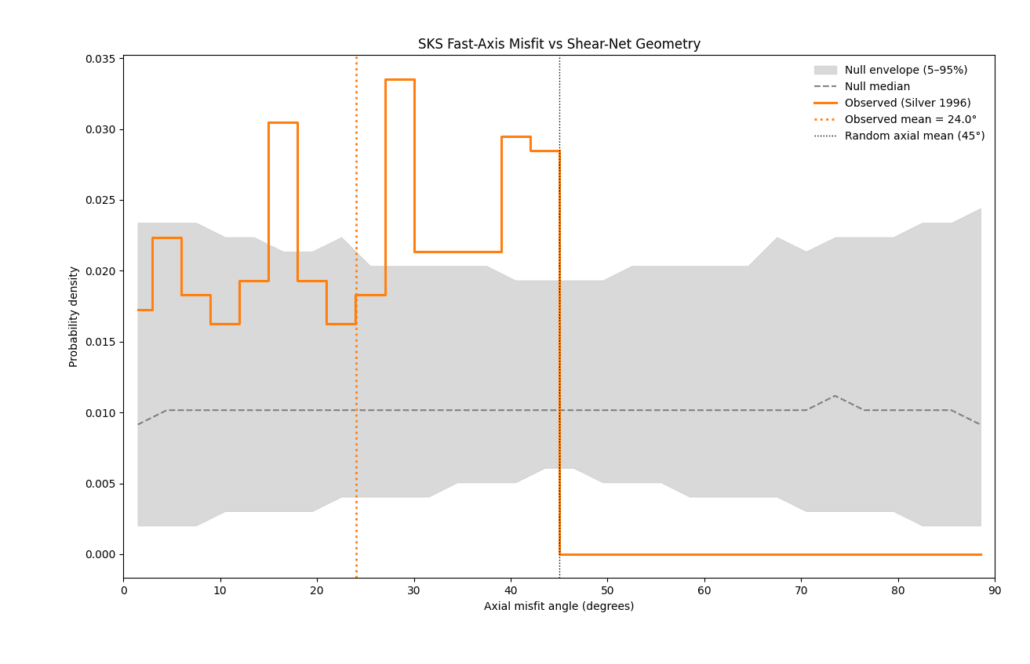

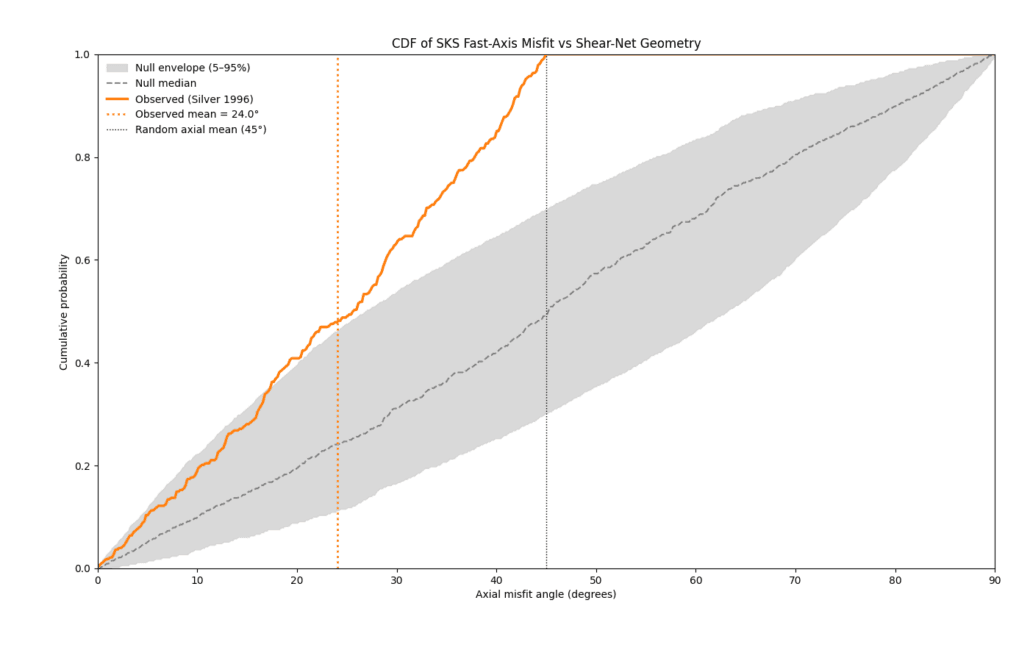

For this study, published global SKS fast-axis orientations compiled by Silver (1996) were compared with the analytically derived shear-net geometry. At each seismic station, the observed fast-axis orientation was compared to the two local shear directions predicted by the model. The angular misfit was defined as the smallest axial angle between the observation and either shear family, bounded between 0° (perfect agreement) and 90° (complete mismatch).

To assess statistical significance without destroying the spatial structure of the data, a global-rotation null test was used. In this approach, all observed SKS orientations are rotated together by a random angle, while station locations are held fixed. Repeating this process many times produces a reference distribution representing random alignment with respect to the modeled shear field, while preserving the real-world geographic sampling.

The results show that the observed SKS orientations are not randomly distributed relative to the shear-net geometry. The mean axial misfit is approximately 24°, substantially lower than the 45° expected for random axial alignment. Monte Carlo testing confirms that both the mean misfit and the spread of misfit values fall outside the range expected from the rotated null ensemble (Figures 23 and 24).

Allowing for the presence of two conjugate shear families improves the absolute agreement between observations and model, but this improvement does not exceed what is expected under the same minimum-selection procedure applied to the null ensemble. This behaviour is consistent with symmetric finite strain in the mantle, where multiple conjugate fabric orientations are geometrically admissible, rather than with a single directed flow alignment.

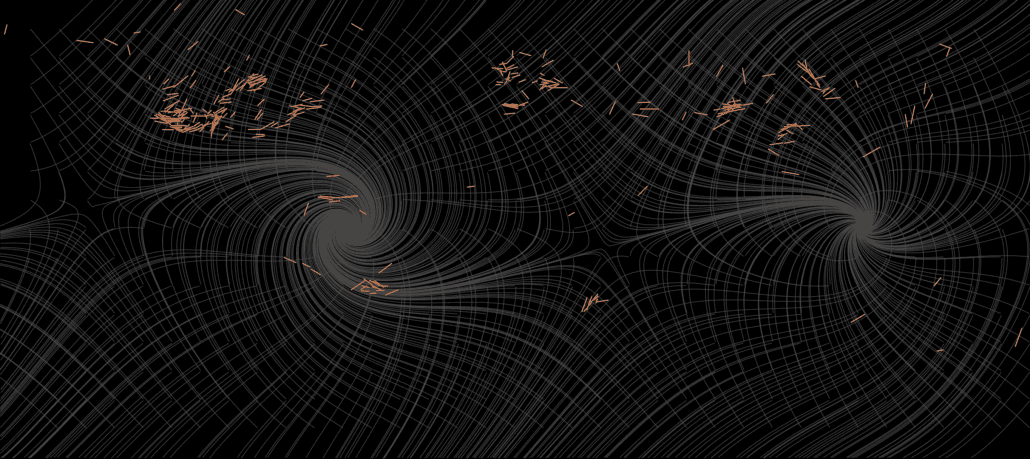

Crucially, the SKS results reinforce a key theme of the paper. While the shear model does not uniquely predict mantle flow directions, the locations where agreement is good or poor are spatially organised rather than random. Mapping the misfit values reveals coherent geographic domains of low and high misfit that extend across tectonic boundaries and, in some cases, across ocean–continent transitions.

This spatial structure mirrors the results obtained from stress-orientation data and from large-scale geological curvature. Regions where mantle anisotropy aligns with the shear framework frequently coincide with areas of persistent arcuate geometry at the surface, while misaligned regions form equally coherent domains elsewhere. The convergence of these independent observations supports the interpretation that the shear-net geometry captures a real, long-wavelength component of Earth’s stress and deformation field.

As with the rest of the study, these findings are interpreted conservatively. The SKS comparison does not establish a causal mechanism, nor does it imply that the modeled shear field dominates mantle flow. Instead, it satisfies a necessary condition for a persistent planetary-scale stress topology: that it leaves detectable, spatially organised imprints not only in surface geology and present-day stress, but also in the long-lived fabric of the upper mantle.

Figure 23 – Distribution of misfit angles between mantle anisotropy and the shear model. This histogram compares observed SKS shear-wave fast-axis orientations with the local shear-net directions. Misfit angles are shown from perfect agreement (0°) to complete mismatch (90°). The shaded band represents what would be expected if orientations were randomly aligned. The observed distribution is clearly shifted toward lower misfit values, indicating that mantle anisotropy is not randomly oriented with respect to the modeled shear geometry.

Figure 24 – Cumulative comparison of observed and random alignment.

This cumulative plot shows the fraction of SKS observations with misfit angles below a given threshold. The observed curve rises more steeply than the random reference envelope, meaning that a larger proportion of observations align closely with the shear-net geometry than would be expected by chance. This reinforces the conclusion that the agreement is systematic rather than accidental.

Figure 25 – Global spatial comparison between the modeled shear-net geometry (gray streamlines) and SKS fast-axis orientations (orange line segments). The spatial distribution shows that SKS observations preferentially occupy regions of coherent shear while avoiding nodal cores of the modeled field. This figure provides spatial context for the statistical results but is not itself used for inference.

Independent Mantle-Scale Test Using SEISGLOB2

The stress-orientation and SKS anisotropy analyses examine how the proposed shear framework is expressed in the lithosphere and uppermost mantle. A further, more demanding test is whether any trace of the same long-wavelength organisation can be detected deeper in the mantle, using an entirely independent class of observations. For this purpose, the study incorporates the global shear-wave velocity tomography model SEISGLOB2, developed by Durand et al. (2017), which images mantle structure down to the lower mantle using a joint inversion of surface waves, normal modes, and body-wave traveltimes.

SEISGLOB2 was not constructed with any reference to the shear-net geometry, true polar wander, or stress-field modelling. It therefore provides a strong independence test: any geometric correspondence must emerge from the data themselves rather than from shared assumptions or tuning. The analysis focuses on whether high-amplitude shear-velocity anomalies show a systematic spatial relationship to the Euler domains predicted by the shear framework, rather than asking whether velocity anomalies simply resemble surface tectonics.

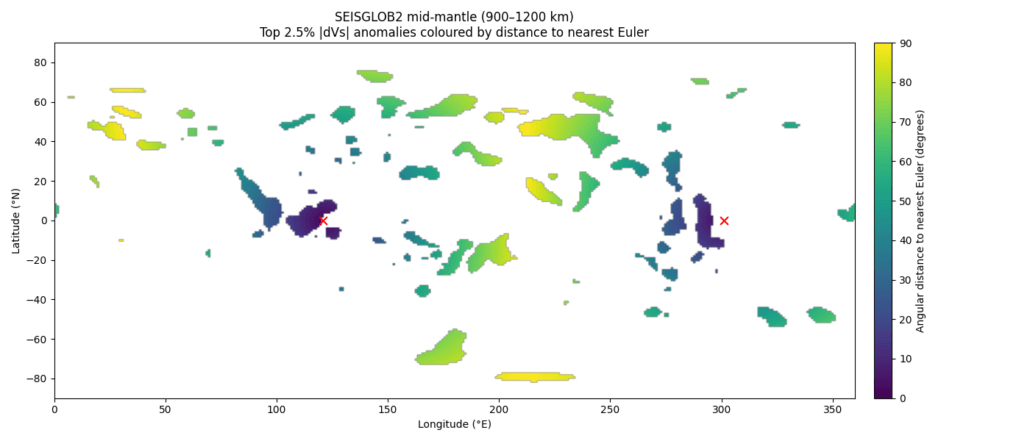

Rather than correlating velocity values point by point, the approach treats the Euler domains as extended kinematic attractors. At each depth interval, grid points corresponding to the strongest velocity anomalies are identified using percentile thresholds of the absolute shear-velocity perturbation. For each anomaly, the great-circle distance to the nearest Euler domain is computed, producing a distribution of distances that quantifies how closely anomalous mantle structure clusters around the predicted shear geometry.

Two conservative null models are used to evaluate significance. In the first, anomaly longitudes are randomised while latitude and depth are preserved, testing whether any apparent Euler proximity could arise purely from latitudinal sampling effects. In the second, latitude is additionally symmetrised about the equator, eliminating hemispheric bias while retaining depth structure and anomaly amplitudes. Both null models preserve the intrinsic characteristics of the tomography while removing any Earth-fixed longitudinal organisation.

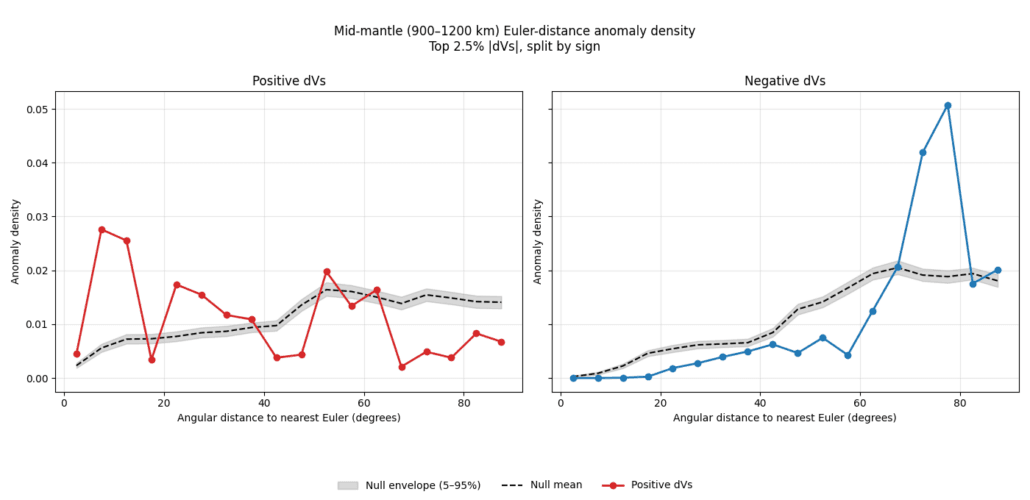

The results reveal a clear and depth-localised signal. A statistically robust shift toward smaller Euler-domain distances appears consistently in the 900–1200 km depth range, indicating that strong shear-velocity anomalies in this interval are preferentially closer to the modeled Euler domains than expected under either null model. Above and below this depth window, the effect weakens or disappears, suggesting that the association is not a generic property of the tomography but is confined to a specific mantle layer.

Sign-resolved analysis further shows that the association is expressed predominantly by low-velocity anomalies rather than high-velocity ones. This asymmetry is consistent with the interpretation that the shear framework preferentially localises deformation or strain accommodation in mechanically weaker mantle regions, rather than merely sampling cold, rigid structures such as slabs. The depth localisation also coincides with a well-documented transition zone in global mantle structure, independently identified in previous tomographic studies.

Importantly, the SEISGLOB2 results do not imply that the shear geometry dictates mantle convection or replaces established interpretations of mantle dynamics. Instead, they indicate that the same long-wavelength geometry inferred from surface stress organisation leaves a detectable imprint at mid-mantle depths, expressed statistically rather than as a visually obvious map correlation. The effect is subtle but systematic, and it emerges only when examined with distance-based metrics designed to capture extended geometric relationships.

Figure 26: Global map of SEISGLOB2 mid-mantle (900–1200 km) shear-velocity anomalies exceeding the 97.5th percentile of |d ln Vs|, coloured by angular distance to the nearest Euler domain. Euler locations are indicated by red crosses. Strong low-Vs anomalies preferentially occupy Euler-proximal basins, consistent with the distributional results shown in Figure 27.

Together with the stress-orientation and SKS anisotropy results, the SEISGLOB2 analysis strengthens the central claim of the paper. The proposed shear framework is not supported by any single dataset in isolation, but by the convergence of independent observations across depth, timescale, and physical domain. The detection of a depth-specific, sign-selective association in global mantle tomography provides an important additional constraint, demonstrating that the inferred shear topology is not confined to surface geology but is compatible with organisation within the deeper mantle.

As elsewhere in the study, the interpretation remains deliberately cautious. Demonstrating geometric association is not the same as identifying a causal mechanism. Nevertheless, the SEISGLOB2 results satisfy a key necessary condition for a persistent planet-scale stress topology: that it produces testable, spatially organised signals detectable even in datasets that were developed entirely independently of the hypothesis.

Figure 27. Mid-mantle (900–1200 km) Euler-distance anomaly density for the strongest 2.5% of |d ln Vs|anomalies in SEISGLOB2, split by anomaly sign. Observed densities for positive (left) and negative (right) anomalies are compared against longitude-randomised null expectations (dashed) with 5–95% envelopes (shaded). Euler-proximal clustering is observed exclusively for negative (low-Vs) anomalies, indicating that the geometric association is expressed preferentially through thermally or mechanically weak mantle structure.

Separating Geometry from Mechanism

It is essential to be clear about the scope of these results. The study does not claim to have identified the physical mechanism responsible for the inferred shear framework. It does not assert that true polar wander occurred in the specific form used to generate the geometry, nor that such a process dominates Earth dynamics today.

The prescribed rotation is a kinematic parameterization — a way of generating a closed-form, long-wavelength shear geometry on the sphere. Alternative parameterizations could produce geometrically similar shear families.

Demonstrating spatial organization is inherently easier than demonstrating causation. The results therefore support a weaker but more robust conclusion: that Earth’s stress field and surface geometry contain signatures consistent with a persistent, planet-scale stress topology.

Integrating these findings with paleomagnetic constraints, mantle-flow models, and geodynamic simulations remains a task for future work.

A New Way to Think About Earth’s Largest Curves

If a long-wavelength shear framework exists, it provides a missing piece between local tectonics and global Earth dynamics. It helps explain why certain geometric forms recur across continents and oceans, why curvature persists through multiple geological regimes, and why directional bimodality is so widespread.

Perhaps most importantly, it suggests that spatial organization itself is a diagnostic signal — one that should be tested explicitly rather than averaged away.

Future work can extend this framework by exploring alternative geometries, integrating seismic anisotropy more fully, and coupling the kinematic model to forward geodynamic simulations. Each of these steps offers a path toward understanding whether the observed geometry reflects deep mantle processes, lithospheric memory, or emergent behaviour of the Earth system as a whole.

For now, the results invite a modest but powerful reframing: Earth’s largest curves may not be accidental. They may be telling us something about the geometry of stress at the scale of the planet.