Orientation of the Sides of the Great Pyramid.

To begin, the reader may be reminded, that the square base of the Great Pyramid is very truly oriented, or placed with its sides facing astronomically due north, south, east, and west; and this fact at once abolishes certain theories to the effect that all the phenomena of that Pyramid have to do with pure geometry alone; for to pure geometry, as well as to algebra and arithmetic, all azimuths or orientations are alike; whereas one most particular astronomical azimuth or direction was picked out for the sides of the base of the Great Pyramid.

In the early ages of the world the very correct orientation of a large pile must have been not a little difficult to the rude astronomy of the period. Yet with such precision had the operations been primevally performed on the Great Pyramid, that the French Academicians in A.D. 1799 were not a little astonished at the closeness. Their Citizen Nouet, “in the month Nivose of their Republican year 7,” made refined astronomical observations to test the error, and found it to be only 19′ 58″; but with the qualification added by M. Jomard, that as M. Nouet had only the ruined exterior of the Pyramid before him to test, the real error of the original surface might have been less. In this conclusion M. Jomard was doubtless correct; for in the similar sort of measure of the angle of the slope of the side, with the base, of the Pyramid, it was proved afterwards (and as we have already shown in Chapter II.), on the discovery of the casing-stones, that his compatriot, spite of all his modern science, had erred to a very much larger extent than the original builders.

As it was, however, then, in this particular question of astronomical orientation, all the Academician authors of the great Napoleonic compilation expressed themselves delighted with the physical and historical proof which the ancient Pyramid seemed to give them, when compared with their own modern French observations of the Polar star, “That the azimuthal direction of the earth’s axis of rotation had not sensibly altered, relatively to the sides of the great Pyramid’s base, during probably 4,000 years.”

Possibility of Azimuthal Change in the Crust of the Earth.

Now some alteration of that kind, one way or the other, has long been a mooted question among astronomers, though chiefly for its bearing on geography, general physics, and geology. In its surface character and linear nature, therefore, it must be kept entirely distinct from the more perfectly astronomical phenomenon, and which few but astronomers attend very closely to—viz. the angular direction of the earth’s axis in space, carrying with it the whole substance of the earth at the same time, and without disturbing the relative position of any of its parts. It is in this latter angular phenomenon, that the mysterious effect of the precession of the equinoxes comes prominently into view, with its slow but accumulating chronological changes from age to age in the apparent times and places of the risings and settings of the stars. But in the former rather geographical, telluric, and more especially surface-differential, light in which the problem was discussed by the French savants of the Revolution, it had also been clearly seen long before, and held to be a worthy cynosure of historical study, by the penetrating genius of the English Dr. Hooke.

For it was this early and ill-paid, but invaluable Secretary of the Royal Society of London, who in his discourse on earthquakes, about the year 1677 A.D., remarks, “Whether the axis of the earth’s rotation hath and doth continually, by a slow progression, vary its position with respect to the parts of the earth; and if so, how much and which way, which must vary both the meridian lines of places, and also their particular latitudes? that it had been very desirable, if from some monuments or records in antiquity, somewhat could have been discovered of certainty and exactness; that by comparing that or them with accurate observations now made, or to be made, somewhat of certainty of information could have been procured.” And he proceeds thus: “But I fear we shall find them all insufficient in accurateness to be any ways relied upon. However, if there can be found anything certain and accurately done, either as to the fixing of a meridian line on some stone building or structure now in being, or to the positive or certain latitude of any known place, though possibly these observations or constructions were made without any regard or notion of such an hypothesis; yet some of them, compared with the present state of things, might give much light to this inquiry. Upon this account I perused Mr. Greaves’ description of the Great Pyramid in Egypt, that being fabled to have been built for an astronomical observatory, as Mr. Greaves also takes notice. I perused his book, I say, hoping I should have found, among many other curious observations he there gives us concerning them, some observations perfectly made, to find whether it stands east, west, north, and south, or whether it varies from that respect of its sides to any other part or quarter of the world; as likewise how much, and which way they now stand. But to my wonder, he being an astronomical professor, I do not find that he had any regard at all to the same, but seems to be wholly taken up with one inquiry, which was about the measure or bigness of the whole and its parts; and the other matters mentioned are only by-the-bye and accidental, which shows how useful theories may be for the future to such as shall make observations; nay, though they should not be true, for that it will hint many inquiries to be taken notice of, which would otherwise not be thought of at all, or at least but little regarded, and but superficially and negligently taken notice of. I find indeed that he mentions the south and north sides thereof, but not as if he had taken any notice whether they were exactly facing the south or north, which he might easily have done. Nor do I find that he had taken the exact latitude of them; which methinks had been very proper to have been retained upon record with their other description.”

Dr. Hooke, however—in mitigation of whose acerbity there is much to be said in excuse, for nature made him, so his biographer asserts, “short of stature, thin, and crooked”—this real phenomenon, Dr. Hooke, “who seldom retired to bed till two or three o’clock in the morning, and frequently pursued his studies during the whole night,” would not have been so hard upon his predecessor in difficult times if he had known, and as we may be able by-and-by, to set forth, what extraordinarily useful work it was that Professor Greaves zealously engaged in when at the Great Pyramid. The Doctor’s diatribes should rather have been at Greaves’s successors to-be, those who were to visit the Great Pyramid in easy, intellectual, scientific times, and then and there do nothing, or mere mischief worse than nothing. Hence it seems to have remained to myself, in 1865, to attempt, at least, to determine with something like modern accuracy the astronomical azimuth of the Great Pyramid; and not only upon its fiducial socket-marks, as defining the ends and directions of the sides of the base, but, still more importantly, on its internal passages.

These passages, long, white-stoned, straight, and of exquisite workmanship, evidently received much of the care of the ancient architect; and though for some deep reasons, enquired into further on,* they were not established by him in the central vertical, and right, plane of the whole Great Pyramid, were yet placed parallel thereto; or, for infinite distance, in the selfsame natural orientation, with astonishing precision.

Popular Ideas of Astronomical Orientation.

In page 26 of George R. Gliddon’s “Otia Ægyptiaca,” that generally acute author does indeed fight against the idea of any astronomical skill in the ancient architect, by suggesting mystically that all this exactness of orientation indicates, amongst the builders of the “pre-antiquity” day of the Great Pyramid, “an acquaintance with the laws of the magnet.” Yet had that been all the founders were possessed of to guide them, the orientation of their great and lasting work might have been in error by ten, or twenty, or thirty degrees or more, in place of only twenty minutes, and, perhaps, far less.

Quite recently too, or within the last six months, on the occasion of a public lecture being given on the Great Pyramid at Ramsgate, an attempt was made by a gentleman-proprietor of the neighbourhood to invalidate the whole of the Great Pyramid subject, because forsooth the lecturer had said nothing about “the Variation of the Compass”; and without that being known, he sententiously informed the Mayor, that “all the rest of the measures were without any value.”

I fear that gentleman must have been misled, like a very worthy friend of mine, a judge too of a great city, and in his day a brilliant classical and philosophical university student,—by having purchased, as a superior means of obtaining true time accurately, a miniature sun-dial mounted on a magnetic needle.

“What can be more perfect?” said he. “Wherever you are, if only the sun shines, the gnomon of the dial is placed due north and south for you by the magic power of the needle, and you have only to read off the time on the hour circle.”

So then I had to explain, what I thought every child of the present scientific age knew long ago; viz. that the end of the magnetic needle marked by the maker NORTH, only points to the real NORTH direction of the earth and the heavens feebly, erroneously, and varyingly.

So feebly, that the smallest imperfection of the central pivot may vitiate the direction of an ordinary waistcoat-pocket compass by several degrees.

So erroneously, either from the magnetic axis of the needle, not coinciding with the shape of the needle, or from the observer having a key or a knife, or a bit of iron or magnetic and attractive rock in his pocket or the neighbourhood, that the needle may be again deflected from its proper position by whole degrees.

And so varyingly, because there are daily, monthly, yearly, and century changes going on in the magnetic elements themselves: wherefore not only are they different in one part of the country from another, but in the same part they differ from age to age; and in the lifetime of the Great Pyramid, the variation of the compass there may have oscillated from west to east of true north 40°, 50°, 60°, and several times over.

The more an astronomer looks into the pointings of a magnetic needle, the more full of serious uncertainties and vagaries he finds it. But the more he examines by mechanical instruments and astronomical observations into the north and south of the axis of the world or the polar point of the heavens, the more admirably certain does he find it and its laws, even to any amount of microscopic refinement.

No astronomer, therefore, in a fixed observatory ever thinks of referring to a magnetic needle for the direction of the north. The very idea, by whomsoever brought up, is simply an absurdity. And of course, in my own observations at the Great Pyramid in 1865, I had nothing to do with occult magnetism and its rude, uncertain pointings, but employed exclusively, for the polar direction, an astronomical alt-azimuth instrument of very solid construction, and reading to seconds. In that way comparing the socket-defined sides of the base, and also the signal-defined axis of the entrance passage, with the azimuth of Alpha Ursæ Minoris, the Pole-star, at the time of its greatest elongation west; and afterwards reducing that observed place, by the proper methods of calculation, to the vertical of the pole itself, the cynosure was reached.

And with what result? Though a tender-hearted antiquary has asked, “Was it not cruel to test any primeval work of 4,000 years ago, by such exalted scientific instruments, and abstruse books of logarithms, as those of the Victorian age in which we live?”

Well, it might be attended with undesired results, if some of the most be-praised works of the present day should ever come to be examined by the advanced instruments of precision of 4,000 years hence; but the only effect which the trial of my Playfair astronomical instrument from the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, had at the Great Pyramid, was to reduce the alleged error of its ancient orientation from 19′ 58″ to 4′ 30″.*

Further Test by Latitude.

In so far, then, this last and latest result of direct observation declares with high probability,—that any relative azimuthal change between the northern direction of the earth’s rotation axis, and a line drawn by man upon its crust 4,000 years ago, such as Dr. Hooke and the French Academicians so greatly desiderated, must, if anything of such change exist at all, be confined within very narrow limits indeed.

This conclusion has its assigned reason here and thus far, solely from observations of angular direction on the horizontal plane of the earth’s surface at the place; and without any very distinct proof being arrived at yet, touching—that though we find the Great Pyramid’s sides at present nearly accordant in angle with the cardinal points of astronomy, they were intended to be so placed by the primeval builder for his own day.

But indication will be afforded presently respecting another test of nearly the same thing, not by angle, but by distance on the surface; and further, that the architect did propose to place the Great Pyramid in the astronomical latitude of 30° north, whether that exact quantity was to be practical or theoretical; while my own astronomical observations in 1865 have proved, from the results of several nights’ work, that it stands so near to 30°, as to be in the latitude parallel 29° 58′ 51″.

A sensible defalcation this, from 30°, it is true, but not all of it necessarily error; for if the original designer had wished that men should see with their bodily, rather than their mental eyes, the pole of the sky, from the foot of the Great Pyramid, at an altitude before them of 30°, he would have had to take account of the refraction of the atmosphere; and that would have necessitated the building standing not in 30°, but in 29° 58′ 22″. Whence we are entitled to say, that the latitude of the Great Pyramid is actually by observation between the two very limits assignable, but not to be discriminated, by theory as it is at present.

The precise middle point, however, between the two theoretical latitudes being 29° 59′ 11″, and the observed place being 29° 58′ 51″, there is a difference of twenty seconds which may have to be accounted for. Though Dr. Hooke’s question upon it would pretty certainly have been, can the earth’s axis have shifted so little in 4,000 years with regard to its crust, that the latitudes of places have altered no more in that length of time than a miserable 20″ of space.

Unfortunately none of the Greek, Roman, Indian, Alexandrian, or any of the older observatories of the world, had their latitudes determined in their day closely enough to furnish additional illustrations for this purpose. Even in Professor Greaves’s time, two hundred and forty years ago, a whole minute of altitude was thought to be an almost superhuman refinement of measure; so that he mentions somewhat fearfully and with bated breath, how a celebrated Italian astronomer, Gaspar Bertius, had credibly informed him when in Rome, “that by repeated observations with a large instrument of Clavius’ he had ascertained that the altitude of the pole there, was 41° and 46′.” And yet if the spot where Bertius observed, were anywhere near either St. Peter’s, or the Collegio Romano, whose latitudes have been well measured in modern times, his result must have been no less than 7′ in error.

At Greenwich, the oldest and best supported of modern European observatories, there has been a continued decrease in its observed latitude with the increase of the time. So that taking up at random the large volumes of its published observations now before me, I find the latitude successively stated as—

In 1776 = 51° 28′ 40·0″

In 1834 = 51° 28′ 39·0″

In 1856 = 51° 28′ 38·2″

This change of 1·8″ in eighty years, implies a quicker rate of decrease than the 20″ at the Great Pyramid in 4,000 years,—if the observations were perfect; but they are not; and it is said, I believe, that small errors in both the instruments and the tables of refraction employed, may be found eventually to explain away the apparent Latitude change.*

Hence all the known practical astronomy of the modern world cannot help us in this matter; and if we apply to physical astronomy, some of its great mathematicians of the day who are supposed to be able to compute anything, and have announced long since how many millions of millions of millions of years the solar system is going to last, these great computers also announced a few years ago that they had found the interior of the earth to be solid, and as stiff as hammered steel; so that no change of latitude could take place. But within the last year, they have concluded again that the interior of the earth is fluid, and steadied only by vortex motion of that fluid; also that in the earlier geological ages, long before man appeared on the scene, great changes of latitude did take place in those almost infinitely long periods; and that, therefore, some small change of the same sort may have been experienced within human history; but it can only be a very small change, even as the Great Pyramid has already indicated.

Testimony, from the Great Pyramid’s Geographical Position, against some recent Earth Theorizers.

In angular distance, then, from the equator, as well as in orientation of aspect, the land of Egypt, by the witness of the Great Pyramid, even if it has changed its latitude a very little, has certainly not changed sensibly for all ordinary, practical men at their usual avocations, in respect to the axis of the earth, during the last 4,000 years.

What therefore can mean some of our observers at home, observers too of the present day, who stand up for having, themselves during their own lifetimes, witnessed the sun at solstice rise and set in an exceedingly different direction by the naked eye from what it does now? I have looked over the papers of two such enthusiasts recently (one in England and the other in Scotland), but without being able to convince them of their involuntary self-deception.*

Again, in the Rev. Bourchier Wrey Savile’s work, “The Truth of the Bible,” published in 1871, that usually very learned and painstaking author (and much to be commended in some subjects) implies, on page 76, that the direction of the sun at the summer solstice is now, at Stonehenge, no less than twelve degrees different from what it was at the time of the erection of that monument, which is probably not more than a third as old as the Great Pyramid. And he quotes freely from, as well as on his own part confirms, a person now dead, one Mr. Evan Hopkins (not the Cambridge mathematician and geologist Hopkins, but a Civil Engineer long in Australia), in asserting “that the superficial film of our globe is moving from south to north in a spiral path, at the rate of seven furlongs in longitude west, and three furlongs in latitude north, every year; whence, he says, the presently southern part of England must have been under a tropical climate only 5,500 years ago.”

This astounding assertion is further supposed, by those parties, to be supported by a quotation from one of the Greenwich Observatory Reports in 1861, wherein Sir George B. Airy remarks that “the transit circle and collimators still present those appearances of agreement between themselves, and of change with respect to the stars, which seem explicable only on one of two suppositions—that the ground itself shifts with respect to the general earth, or that the axis of rotation changes its position.” But I can venture to be professionally confident that Sir G. B. Airy did not mean to support any such assertion as Mr. Evan Hopkins’s and Mr. W. B. Savile’s, by that mere curiosity of transcendental refinement in one year’s instrumental observation, which he was alluding to in one number of a serial document; a something of possible change, too, which is so excessively small (an angle subtending perhaps the apparent thickness of a spider’s line at the distance of fifty feet), that no one can be perfectly certain that it ever exists; a something which small heat expansions of the instrument may easily produce; and which, if found at any given epoch, does not go on accumulating continually in one direction with the progress of time, as it would do if dependent on a grand cosmical cause.

To confirm, too, this much more sober view of the nearly solid earth we live upon, the Great Pyramid adds all its own elder and most weighty testimony to that both of Greenwich and every public observatory with good astronomical instruments throughout Europe, by declaring the world’s surface to be remarkably constant to the cardinal directions, for as long as it has been accurately observed. And thus it may come to pass at last, that there will yet be monumentally proved, from the earliest human times to the present, to be more of “the truth of the Bible” bound up with both the scientific definition, and exactly observed constancy through long ages, of astronomical orientations, as well as geographical directions and positions,—than has yet entered into many persons’ modern philosophies.

* I am happy to say, in 1879, that the Scottish case has come all right; or the ultra-honest old gentleman recently assured me that six more years’ experience had shown him how to guard against his earlier error in making the observation on the sloping side of a hill, and he is convinced now that there is nothing wrong about the Sun.

Geographical Aptitudes of the Great Pyramid.

With the general’s glance of a Napoleon Bonaparte himself, his Academician savants in Egypt, in 1799,

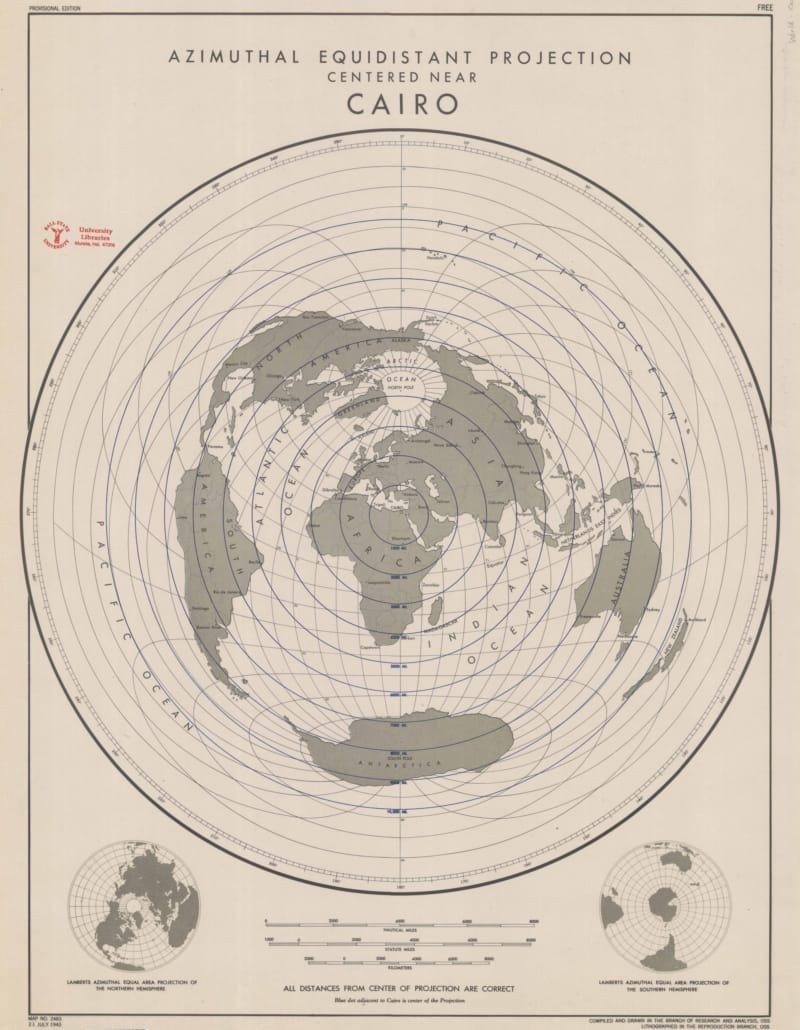

perceived how grand, truthful, and effective a trigonometrical surveying signal the pointed shape of the Great Pyramid gratuitously presented them with; and they not only used it for that purpose, as it loomed far and wide over the country, but employed it as a grander order of signal also, to mark the zero meridian of longitude for all Egypt.

In coming to this conclusion, they could hardly but have perceived something of the peculiar position of the Great Pyramid at the southern apex of the Delta-land of Egypt; and recognized that the vertical plane of the Pyramid’s passages produced northward, passed through the northernmost point of Egypt’s Mediterranean coast; besides forming the country’s central and most commanding meridian line. While the N.E. and N.W. diagonals of the building similarly produced, enclosed the fertile Delta’s either side in a symmetrical and well-balanced manner. (See Plate II.) But the first very particular publication on this branch of the subject was by Mr. Henry Mitchell, Chief Hydrographer to the United States Coast Survey.

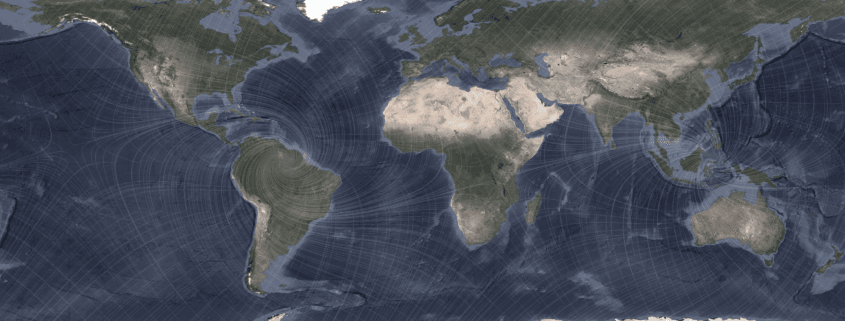

That gentleman having been sent, in 1868, to report on the progress of the Suez Canal, was much struck with the regularity of a certain general convex curvature along the whole of Egypt’s, “Lower Egypt’s,” northern coast. To his mind, and by the light of his science, it was a splendid example, on that very account, of a growing and advancing coast-line, developing in successive curves all struck one after and beyond the other from a certain central point of physical origination in the interior.

And whereabouts there, was that physical centre of natural origin and formation?

With the curvature of the northern coast, really the Delta-land of the Nile, on a good map before him (see, in a very small way, our Fig. 1, Plate II.), Mr. Mitchell sought, with variations of direction and radius carried southward, until he had got all the prominent coast-points to be evenly swept by his arc; and then looking to see where his southern centre was, found it upon the Great Pyramid: immediately deciding in his mind, “that that monument stands in a more important physical situation than any other building yet erected by man.”

On coming to refinements, Mr. Mitchell did indeed allow that his radii were not able to distinguish between the Great Pyramid and any of its near companions on the same hill-top. But the Great Pyramid had already settled that differential matter for itself; for while it is absolutely the northernmost of all the Pyramids (in spite of one apparent, but false, exception to be explained further on), it is the only one which comes at all close—and it comes very close—to the northern cliff of the Jeezeh hill. Almost overhangs it, and the Delta too; so that the Great Pyramid thence looks out with most commanding gaze over the open-fan-shaped, fertile, and human-food producing land of Lower Egypt; looking over it, too, from the sectorial land’s very “centre of physical origin”; or as from over the handle of the fan, outward to the far-off curved sea-coast. All the other Pyramids are away back on the table-land, so far to the south of the Great one that they lose that grand view from the front or northern edge of the hill. They even appear, one might almost say, in a mere menial, inferior position, away there behind, as being in a manner the suite and following train only, of the Great building; that mysterious Great one who is the unquestioned owner there, and seems to have thoughts, beyond their thoughts, as he gazes, Napoleon-wise, over that primevally fertile, historic, triangular plain right away before and immediately below him.

So very close was the Great Pyramid placed to the northern brink of its hill, that the edges of the cliff might have broken off, under the terrible pressure, had not the builders banked up there most firmly the immense mounds of rubbish which came from their work; and which Strabo looked so particularly for, 1,850 years ago, but could not find.* Here they were, however, and still are, utilised in enabling the Great Pyramid to stand on the very utmost verge of its commanding hill, within the limits of the two required latitudes, 30° and 29° 58′ 23″, as as well as over the centre of the land’s physical and radial formation; and at the same time on the sure and proverbially wise foundation of rock.†

Now Lower Egypt being, as already described, of a sector shape, the building which stands at, or just raised above, its sectorial centre must be, as Mr. Henry Mitchell has acutely remarked, at one and the same time both at the border thereof, and in its quasi middle; or, just as was to be that prophetic monument, pure and undefiled in its religion though in an idolatrous land, alluded to by Isaiah (ch. xix.), the monument which was fore-ordained as both “an altar to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt, and a pillar at the border thereof”; destined moreover to become a most special witness in the latter days, before the consummation of all things, to the same Lord, and to what He hath purposed upon mankind.

Whether the Great Pyramid will eventually succeed in proving itself to be really the one and only monument alluded to under those glorious terms or not, it has thus far undoubtedly most unique claims for representing much that is in them, both as to its circumstances of mechanical fact and surrounding chorography; while its general characteristics of situation, not unworthy of the one and only known, existing monument of Inspiration, by no means end there. For proceeding along the globe due north and due south of the Great Pyramid, it has been found by a good physical geographer as well as engineer, Mr. William Petrie, that there is more earth and less sea in that meridian than in any other meridian all the equator round. Hence, therefore, the Great Pyramid’s meridian is caused to be as essentially marked by nature, in a general manner, across the world from Pole to Pole, or rather from the North Cape of Norway to the diamond fields and Zulu-and of South Africa, as a prime meridian for all nations measuring their longitude from, or for that modern cynosure “the unification of longitude,”—as it is more minutely marked by art and defined by human work within the limits of the Lower Egyptian plain, by the pointed building itself alone.

Again, taking the distribution of land and sea in parallels of latitude, there is more land-surface in the Great Pyramid’s general parallel of 30°, than in any other degree; so that the two grand, solid, man-inhabited earth-lines, the one, of most land in any Meridian, and the other of most land in any Latitude, cross on the Great Pyramid. And finally, on carefully summing up the areas of all the dry land habitable by man all the wide world over, the centre of the whole falls within the Great Pyramid’s special territory of Lower Egypt.*

But, as Commodore Whiting, U.S. Navy, writes to me recently from America, the Great Pyramid’s further, and even chief claim in his eyes to attention as a Zero of all nations’ Longitude, is not merely that it is so eminently set in the midst, among all the busier haunts of men, on its own side of the earth; but that its Nether-Meridian, or the continuation of its Egyptian Meridian round the opposite side of the world, forms the most suitable possible line of locality for circumnavigators of the globe to change their day of reckoning, as they pass it, accordingly as they are proceeding from East to West, or from West to East; because, that Nether-Meridian of the Great Pyramid ranges its whole length from South to North Pole, excepting only near Behring’s frozen Straits, through foaming, tossing, sea: realizing therefore almost exactly the precise Nether-Meridian long desired by the late most eminent Captain Maury, in his grand, and world-wide facilitations of the Navigation of all Nations.

* See my “Equal Surface Projection,” published in 1870 by Edmonston and Douglas, Edinburgh. See also Fig. 2 of Plate II., in this book.